During World War II, the legal academy was virtually uncritical of the government’s conduct of the war, despite some obvious domestic abuses of civil rights, such as the internment of Japanese-Americans. This silence has largely been ignored in the literature about the history of legal education. This Article argues that there are many strands of causation for this silence. On an obvious level, World War II was a popular war fought against a fascist threat, and left-leaning academics generally supported the war. On a less obvious level, law school enrollment plummeted during the war, and the numbers of full-time law professors dropped by half. Of those professors “laid off” during the war, many took employment in government agencies and thus effectively silenced themselves. Finally, the American Association of Law Schools had only adopted a strong position on academic freedom and tenure in 1940. The commitment to academic freedom and tenure was insecure in many institutions and was only weakened by the severe economic strain of the war. To illustrate the effect of these larger forces, this Article tells the stories of five professors who criticized domestic policy during the war and the institutional consequences of their dissent. Of those professors, only one - a tenured professor at New York University - was fired during the war. While the basic building blocks of legal academies are the same today as they were in World War II, other factors such as strong institutional commitments to academic freedom and tenure, a robust First Amendment, and economic prosperity have significantly changed the roles that law professors are empowered to play in society, most significantly as the watchdogs of government.

Monday, January 31, 2011

Ludington on Academic Freedom, Tenure, and the Silence of the Legal Academy During WW II

A note about comments

Jury Duty and the History of U.S. Colonialism

Among the many stacks of paper on my desk, two sit suggestively side by side. One contains assorted personal business, and at the top, a reminder notice from the Office of Jury Commissioner that I must report for jury duty next week. If I might grumble about it, I’m reminded that “[t]he Framers of the United States Constitution considered both the right to a jury trial and the performance of juror service as sacred and necessary to preserve individual freedom,” and that jury service is “a duty and privilege of citizenship, and [] a necessary check against government use of the courts to wrongly convict the innocent.” The second stack contains primary documents from my research on the Philippines under U.S. colonial rule. My imprecise document organization system for now involves using post-it notes to label my stacks of paper. This post-it reads “The Jury System.”

If the framers of the U.S. Constitution considered the right to a jury trial an essential check on the government, just over a century later, the framers of the U.S. colonial state in the Philippines considered it a threat to the efficient administration of the law, and to the sovereignty of the American state.

At the turn of the twentieth century, American colonial officials in the Philippines boasted that, under under U.S. rule, the islands' courts would “secure to the people [that] which they most earnestly desire, a pure, honest, and able administration of the law.” In their report to President McKinley, the first civil commissioners sent to the archipelago, wrote back that the people of the Philippines wanted the opposite of “arbitrary penalties,” “private laws,” and “special tribunals.” “In their consciousness,” the commissioners wrote, “it is not political privileges and franchises, but personal and civil rights and liberties, which occupy the foreground.” U.S. claims to legitimate rule of the islands rested, in part, on a claim that Filipino revolutionaries were most concerned, not with national political sovereignty, but rather with gaining the civil rights and liberties that they had been denied under Spanish colonial rule. But while President McKinley instructed the new government in the Philippines to provide many of the guarantees of the Bill of Rights, he did not instruct them to provide for the right to trial by jury.

William H. Taft, first Civil Governor of the islands under U.S. rule, and other officials, believed that Filipinos were not yet ready to exercise the full rights and obligations of citizens in the islands’ courtrooms. U.S. officials had a racialized vision of the U.S. law reform project in the islands, under which particular procedures and institutions would have to await the completion of America’s “civilizing” mission. That bulwark of individual liberty “had no place among an ignorant people,” Taft wrote in Four Aspects of Civic Duty (1906). According to Taft, the jury system called upon ordinary citizens to take responsibility for “the good working of government and for the best interest of society at large.” “It is this sense of justice,” he argued, “which is implanted naturally in the Anglo-Saxon breast, but which is absent in the Porto Rican or Filipino.”

While U.S. territorial policy carved out exceptions to the procedural protections for individual liberties in American law, the U.S. Supreme Court gave that policy constitutional authority. Writing for the majority in Dorr v. United States (1904), Justice Day explained that “whatever other limitations [Congress] may be subject,” it is not obligated to provide “a system of laws which shall include the right of trial by jury, and that the Constitution does not, without legislation and of its own force, carry such right to territory so situated.”

The two stacks of paper on my desk reflect a tension between the apparent inviolability of the jury system in American culture, and the history of U.S. territorial governance and American constitutional law concerning the institution. I’ll need to bring some reading material with me for the hours of waiting that generally come with jury duty, and I still have plenty of documents to work through in my pile of papers marked “The Jury System.” Perhaps I’ll bring those. But I’d be delighted if anyone has suggestions for jury duty day reading on the history of juries in the U.S. or elsewhere. Feel free to post in the comments.

This is my final post for the month. Thanks to Dan, Mary, Karen, and the LHB readers for the chance to be a guest blogger.

Malone reviews Darian-Smith, "Religion, Race, Rights"

The Law & Politics Book Review (sponsored by the Law and Courts Section of the American Political Science Association) has just posted a review of Eve Darian-Smith, Religion, Race, Rights: Landmarks in the History of Modern Anglo-American Law (Oxford and Portland: Hart Publishing, 2010).

The Law & Politics Book Review (sponsored by the Law and Courts Section of the American Political Science Association) has just posted a review of Eve Darian-Smith, Religion, Race, Rights: Landmarks in the History of Modern Anglo-American Law (Oxford and Portland: Hart Publishing, 2010).Here's a taste, from reviewer Christopher Malone (Department of Political Science, Pace University):

The chasm between the emancipatory assurances of Anglo-American law and its more ominous, less than noble history lies at the center of Eve Darian-Smith’s incredibly ambitious – and in some ways too ambitious – work, RELIGION, RACE RIGHTS: LANDMARKS IN THE HISTORY OF MODERN ANGLO-AMERICAN LAW. Professor Darian-Smith challenges the notion that western modern law is “the source of equal protection and enforceable rights for all” (p.18). Rather, she seeks to “underscore the sacred, irrational and ideological elements embodied in law” (p.2). Darian-Smith demonstrates “that today’s western understanding of the rule of law is historically grounded to the particularities of Christian morality, the institutional exploitation of minorities, and specific conceptions of state and individual rights” (p.2).The work selectively reaches back over five hundred years of Anglo-American law and events – from the emergence of Martin Luther and the onset of the Reformation, to the arrival of Sam Walton and the global capitalist expansion of his Walmart empire.Malone concludes by recommending the book to "anyone whose academic work even remotely touches on the issues of religion, race, and rights." He also suggests the book as a reference work "for any others interested in the last five hundred years of Anglo-American law."

While Darian-Smith’s thesis is that modern western law is not nor ever has been rational, objective, and secular, she offers a persuasive counter-argument largely backed up through the evidence: the proper norm to view Anglo-American law over the last five centuries is through religious exclusion on the one hand and racial discrimination on the other (the latter of which has been fueled by capitalist exploitation). And while Darian-Smith does not frame the argument directly in this way, RELIGION, RACE, RIGHTS could also be read broadly as a meditation on the debate between the false promises of classical liberalism and the dangerous excesses of communitarianism. While [*15] the former begins with a “methodological individualism” which views societies through the lens of the abstracted individual whose “natural rights” are protected by the social contract, the latter counters that the “individual” cannot and does not exist outside of the groups which historically, culturally, and ideologically circumscribe one’s society. As much as we would like to believe in the existence of a society of free, equal individuals protected by the rule of law, we are consistently met with the reality of an in-group/out-group dynamic, mostly not of our choosing, that both initiates and is exacerbated by a constant power dynamic. At its worst, this dynamic leads to conflict, bloodshed, discrimination, and social upheaval.

You can read the full review here.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

Obama's Wars, Supreme Court History, and more in the book reviews

The rest is here.a book about "just war" theory in which he concludes that Barack Obama, a president he clearly admires, has prosecuted the war on terror with no more regard for the theory’s ancient principles than George W. Bush (whom many of Carter’s readers no doubt consider a war criminal). The really discomfiting part is that Carter doesn’t advance this claim as a criticism, but rather as an acknowledgment of the way America’s leaders fight wars, and are quite likely to continue fighting this one.

Inherently Unequal: The Betrayal of Equal Rights by the Supreme Court, 1865-1903 by Lawrence Goldstone is taken up this week in the Los Angeles Times. Steve Oney writes:

In the years immediately following the Civil War, America appeared to possess the will and the means to end racial segregation and give the same rights enjoyed by whites to its 4 million recently freed black slaves. These noble goals, of course, were not achieved for another century. During the intervening decades, the South saw the rise of Jim Crow and Judge Lynch. In "Inherently Unequal,"...Lawrence Goldstone convincingly lays the blame for this tragedy at the door of the institution that could have made the difference but did not: the United States Supreme Court.Continue reading here.

THE NEOCONSERVATIVE PERSUASION: Selected Essays, 1942-2009, by Irving Kristol, Edited by Gertrude Himmelfarb, is reviewed in the New York Times; Theodore Roosevelt’s History of the United States: His Own Words, Selected and Arranged by Daniel Ruddy, is taken up in The New Republic's The Book; and INVENTING GEORGE WASHINGTON: America’s Founder, in Myth & Memory by Edward G. Lengel is reveiwed in the Boston Globe.

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Weekend Round-up

- The National Book Critics Circle finalists this year include, in non-fiction: Barbara Demick, Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea; S.C. Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History; Jennifer Homans, Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet; Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer; and Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration. Ralph Luker has the rest here.

- Just in time to serve as an object lesson to the students in my New Deal Legal History seminar before we troop over to the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress there appeared this story of a researcher's falsification of the date on a famous pardon by Abraham Lincoln. DRE

R.I.P. Harvard sociologist Daniel Bell. One of the last of the "New York intellectuals," Bell's publications include Marxian Socialism in the United States (1952), The End of Ideology (1960), and The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1978). Obituaries are here, here, and here. (image credit)

R.I.P. Harvard sociologist Daniel Bell. One of the last of the "New York intellectuals," Bell's publications include Marxian Socialism in the United States (1952), The End of Ideology (1960), and The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1978). Obituaries are here, here, and here. (image credit)

- Over at the Faculty Lounge, Al Brophy has posted an update on the status of "the second volume of the Morton Horwitz festschrift" (Transformations in American Legal History: Law, Ideology, and Methods -- Essays in Honor of Morton Horwitz). You can read his commentary and see the TOC here.

- Religion in American History (a group blog on American religious history and culture) has posted a two-part interview with David Sehat, author of The Myth of American Religious Freedom (Oxford University Press, 2010). (Part I, Part II)

- From Out of the Jungle, news that a digitization project at the Kennedy Library is not including papers of Robert Kennedy, which are "'stacked in a vault at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum ... , individually sealed and labeled.' They amount to '54 crates of records so closely guarded that even the library director is prohibited from taking a peek.'" More here.

Friday, January 28, 2011

H-Law seeks book review editor

H-LAW seeks an engaged, interested and energetic scholar for high-visibility appointment as an H-LAW book review editor. Applicants should be willing to assume responsibility for a wide range of subjects in the fields of legal and constitutional history, both American and non-American. H-LAW book review editors have the full support of the H-LAW editorial board, including the contribution of reviews. Junior scholars are encouraged to apply. Interested applicants, whether experienced book review editors or not, should send a short letter of interest and a copy of their CV to Charles L. Zelden, Chair of the Book Review Editor Search Committee [zelden@nova.edu]. Review of applications will begin immediately and the search will continue until the position is filled.Professor Zelden adds this "personal aside":

I was book review editor for H-Law for ten years. I found the job a useful way to keep current with research in the field (in fact, it introduced me to topics I would not otherwise have studied) and to network within the profession at a time when I was just starting out.If you're at all interested -- even simply curious about what the position entails -- I encourage you to reach out to Professor Zelden or others on the H-Law board. We routinely post H-Law reviews, so we have a vested interest in the success of this search!

Opening of the J.P. Coleman Papers

image creditThe Archives & Special Collections at the University of Mississippi is pleased to announce the opening of Fifth Circuit papers of Judge J.P. Coleman. To commemorate the occasion, the archive is hosting a program in the J.D. Williams Library on Tuesday, March 8th at 5:30 p.m. Judge Leslie Southwick of the Fifth Circuit will discuss the nomination and confirmation of Coleman, John B. Clark (senior partner of Daniel, Coker, Horton, and Bell in Jackson, MS) will recall his service as the judge’s law clerk, and Dr. John Winkle of the UM Political Science Department will address the realignment of the Fifth Circuit Court with particular attention to Coleman’s role in the process. The event is open to the public and also approved for one hour of Mississippi CLE and judicial education credit.

Born in 1914, J.P. Coleman had an active career in state politics: district attorney for the Fifth Circuit of Mississippi, state circuit judge, Mississippi Supreme Court justice, state attorney general, Mississippi governor, and Mississippi legislator. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Coleman to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. Although opposed by civil rights groups, the Senate confirmed the appointment.

Coleman served on the Fifth Circuit bench for nineteen years. During that period, he ascribed to color-blind, narrow constitutionalist interpretations that favored law enforcement against direct-action protest, supported local control of school operations, and restricted claims based upon employment discrimination and voting rights. In Connor v. Johnson, Coleman was part of a District Court panel that rejected a Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party challenge to the legislature’s 1966 reapportionment plan eliminating all majority black districts within the state.

Coleman became Chief Judge in 1979 and the following year relented to proposals for realignment that placed Mississippi in a western division retaining the designation “Fifth Circuit” while the eastern division transformed into the “Eleventh Circuit.” Congressional legislation authorizing the reorganization passed on October 1, 1981. Coleman assumed senior status in 1981 and retired from the bench in 1984. He died on September 28, 1991 and his body lay in state in the Old Capitol in Jackson, Mississippi prior to burial.

The J.P. Coleman Collection finding aid is available online here. Please direct any questions about the program or the collection to Leigh McWhite at 662-915-1850 or slmcwhit@olemiss.edu.

Leigh McWhite, Ph.D.

Political Papers Archivist & Assistant Professor

University of Mississippi

(662) 915-1850

Thursday, January 27, 2011

New Blog: Ancient Traditions, New Conversations

The blog is updated with new original content each Tuesday. In recent weeks Jessica Marglin, a PhD candidate in Princeton’s Near Eastern Studies department and a first year fellow at the Center for Jewish Law, has written a thought provoking review of Gideon Libson’s Jewish and Islamic Law: A Comparative Study of Custom during the Geonic Period. Previous blog entries have included a fascinating halakhic analysis of privacy on the Internet by Aryeh Amihay, a PhD candidate in Princeton's Religion department and a second year fellow at the CJL, and a well-reasoned review of Jeff McMahan's Killing in War by Shalom Carmy, co-chair of the Jewish Studies Department at Yeshiva College.I am adding the blog to our blogroll, so that LHB readers can easily find it in the future. Welcome to Ancient Traditions, New Conversations!

Over the coming weeks and months you can expect to see many other exciting essays and reviews on our site. Additionally, links to relevant content from throughout the web - along with brief commentary – are posted daily in a section entitled “Link Roundup.”

Bessler on Cesare Beccaria, the Enlightenment, America's Death Penalty, and the Abolition Movement

In 1764, Cesare Beccaria, a 26-year-old Italian criminologist, penned On Crimes and Punishments. That treatise spoke out against torture and made the first comprehensive argument against state-sanctioned executions. As we near the 250th anniversary of its publication, law professor John Bessler provides a comprehensive review of the abolition movement from before Beccaria's time to the present. Bessler reviews Beccaria's substantial influence on Enlightenment thinkers and on America's Founding Fathers in particular. The Article also provides an extensive review of Eighth Amendment jurisprudence and then contrasts it with the trend in international law towards the death penalty's abolition. It then discusses the current state of the death penalty in light of the U.S. Supreme Court's recent decision in Baze v. Rees and concludes that there is every reason to believe that America's death penalty may finally be in its death throes.

Law & Society Workshop at Indiana Law

Thursday, Jan. 27, 2011

Camille Walsh

Indiana University Jerome Hall Postdoctoral Fellow

"'We Are Tax Paying Citizens': Educational Equality Litigation in the U.S., 1929-1959"

Thursday, Feb. 3

Alasdair Roberts

Suffolk University Law School

"The Rise and Fall of Discipline: Economic Globalization, Administrative Reform, and the Financial Crisis"

Thursday, Feb. 10

Ed Watts

Indiana University Department of History

"Roman Anti-Pagan Legislation in Theory and Practice"

Thursday, March 24

Joanna Grisinger

Clemson University Department of History

"The Unwieldy State: Administrative Politics after 1945"

(Co-sponsored with IU History)

Thursday, April 7

Ho-fung Hung

Indiana University Department of Sociology

"Justice and Protest with Chinese Characteristics, Past and Present"

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Conversations in Law and Society: Edelman interviews Friedman, et al

The roster of interviewees is impressive: the first three were Joseph R. Gusfield (Professor of Sociology Emeritus, University of California, San Diego), Stewart Macaulay (Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Wisconsin-Madison), and Lawrence Friedman (Marion Rice Kirkwood Professor of Law and Professor of History and Political Science, Stanford University) (pictured at right). Laura Nader (Professor of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley) and Marc Galanter (Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Wisconsin-Madison) are on deck.

The roster of interviewees is impressive: the first three were Joseph R. Gusfield (Professor of Sociology Emeritus, University of California, San Diego), Stewart Macaulay (Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Wisconsin-Madison), and Lawrence Friedman (Marion Rice Kirkwood Professor of Law and Professor of History and Political Science, Stanford University) (pictured at right). Laura Nader (Professor of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley) and Marc Galanter (Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Wisconsin-Madison) are on deck.Videos of the interviews are available on the Center's website.

Vermeule and Lanni on Ancient Constitutional Design

Image credit: ZalecusThis paper identifies two distinctive features of ancient constitutional design that have largely disappeared from the modern world: constitution-making by single individuals and constitution-making by foreigners. We consider the virtues and vices of these features, and argue that under plausible conditions single founders and outsider founders offer advantages over constitution-making by representative bodies of citizens, even in the modern world. We also discuss the implications of adding single founders and outsider founders to the constitutional toolkit by describing how constitutional legitimacy would work, and how constitutional interpretation would be conducted, under constitutions that display either or both of the distinctive features of ancient constitutional design.

Purcell reviews Zelden on Bush v. Gore

Edward Purcell, New York Law School, takes up Charles Zelden's Bush v. Gore, a contribution to the Landmark Cases and American Society series of the University Press of Kansas, in an H-Law review. Professor Purcell concludes:

Edward Purcell, New York Law School, takes up Charles Zelden's Bush v. Gore, a contribution to the Landmark Cases and American Society series of the University Press of Kansas, in an H-Law review. Professor Purcell concludes:The subtlety and breadth of Zelden’s analysis precludes easy summary. Suffice it to say that, even in abridged form, the book tells the story of Bush v. Gore ably and comprehensively, treats highly controverted issues with fairness and intelligence, and offers a range of insights and conclusions sufficient to enlighten and stimulate any reader.More.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

CFP: U.S. Intellectual History Conference

The Intellectual History Blog has posted a call for papers for the 2011 U.S. Intellectual History Conference in New York City. This will be the fourth annual USIH conference put on by the Society for U.S. Intellectual History. This year’s conference theme is “Narratives,” and Pauline Maier will deliver the keynote address. I had a wonderful experience at the USIH conference when I presented a paper in 2009. It is a great conference for graduate students and a great opportunity for legal historians whose work has an intellectual history component to get feedback from scholars in intellectual history.

Here’s the CFP:

Call for Papers

U.S. Intellectual History: Narratives

Fourth Annual U.S. Intellectual History Conference

and Annual Meeting of the Society for U.S. Intellectual History

Co-sponsored and hosted by the Center for the Humanities,

The Graduate Center of the City University of New York

New York City

November 17-18, 2011

Submission deadline: June 15, 2011

The Conference Committee of the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH) invites paper and panel proposals for its fourth annual conference, to be held at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, on November 17-18, 2011. S-USIH is very pleased to announce that the keynote address will be delivered by Pauline Maier of MIT, author of Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 and American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence.

This year’s conference theme is “Narratives.” The theme highlights the fact that stories are essential to the study of American thought. Intellectual historians catalogue and interpret the narratives used by the figures they study, and construct narratives themselves in composing their own accounts of the past. The committee invites participants not only to reflect on narrative itself, but to compare and contrast it with other forms of expression, such as argument or declaration. While proposals that relate to the theme are particularly welcome, the conference committee encourages all submissions that are relevant to any aspect of U.S. intellectual history.

The most typical panels will feature three academic papers and one commentator, who will also serve as the panel chair. But submissions for sessions that will use other formats are also invited. Varieties of alternate sessions might include: roundtables (a series of ten-minute extemporaneous presentations on a topic followed by discussion among the panel and audience), discussion panels (in which the papers are circulated online in advance of the conference and the entire session is devoted to discussions of them), brownbags (one-hour long, lunchtime presentations), “author meets critics” events, retrospectives on significant works or thinkers, interviews, or performances. The conference organizers are happy to consider any proposed format that will fit a two-hour long session slot or a one hour-long lunch session (though session organizers should be aware that there are fewer of the latter than the former).

Submissions of both individual papers and complete panels (or alternate-format sessions) will be accepted, as well as applications from those who would be interested in moderating a session. Paper submissions should feature a 200-word abstract of the paper itself, and a one-page CV. Panel proposals must include an abstract of each presentation, a separate description of the panel itself, and one-page CVs for all participants. Submissions for alternate-format sessions must also include a full description of the proposed format. Those interested in chairing a session or commenting should send a CV indicating areas of expertise and interests. All submissions must include a postal and email address, and phone number for each participant. Individual papers in traditional panels should last no more than twenty minutes. All persons appearing on the program will be required to register for the conference and to become members of S-USIH.

All submissions must be emailed as attachments in MS Word or Google docs format. Deadline for submissions is Wednesday, June 15, 2011.

| Send all submissions to: | Other queries may be directed to: |

| S-USIH 2011 Conference Committee | Mike O’Connor |

| usih.2011@gmail.com | S-USIH Conference Committee Chair |

| oconnor@gsu.edu |

Garland, Peculiar Institution: America's Death Penalty in an Age of Abolition

The latest to cross my desk (a 2010 publication -- I'm catching up!), is David Garland, Peculiar Institution: America's Death Penalty in an Age of Abolition, with a review from Justice Stevens. Here's the book description:

The U.S. death penalty is a peculiar institution, and a uniquely American one. Despite its comprehensive abolition elsewhere in the Western world, capital punishment continues in dozens of American states– a fact that is frequently discussed but rarely understood. The same puzzlement surrounds the peculiar form that American capital punishment now takes, with its uneven application, its seemingly endless delays, and the uncertainty of its ever being carried out in individual cases, none of which seem conducive to effective crime control or criminal justice. In a brilliantly provocative study, David Garland explains this tenacity and shows how death penalty practice has come to bear the distinctive hallmarks of America’s political institutions and cultural conflicts.

America’s radical federalism and local democracy, as well as its legacy of violence and racism, account for our divergence from the rest of the West. Whereas the elites of other nations were able to impose nationwide abolition from above despite public objections, American elites are unable– and unwilling– to end a punishment that has the support of local majorities and a storied place in popular culture.

In the course of hundreds of decisions, federal courts sought to rationalize and civilize an institution that too often resembled a lynching, producing layers of legal process but also delays and reversals. Yet the Supreme Court insists that the issue is to be decided by local political actors and public opinion. So the death penalty continues to respond to popular will, enhancing the power of criminal justice professionals, providing drama for the media, and bringing pleasure to a public audience who consumes its chilling tales.

Garland brings a new clarity to our understanding of this peculiar institution– and a new challenge to supporters and opponents alike.

A snippet from Justice Stevens' review:

“Some of [Garland’s] eminently readable prose reminds me of Alexis de Tocqueville’s nineteenth-century narrative about his visit to America; it has the objective, thought-provoking quality of an astute observer rather than that of an interested participant in American politics...In his view, an important reason Americans retain capital punishment is their fascination with death. While neither the glamour nor the gore that used to attend public executions remains today, he observes, capital cases still generate extensive commentary about victims’ deaths and potential deaths of defendants. Great works of literature, like best-selling paperbacks, attract readers by discussing killings and revenge. Garland suggests that the popularity of the mystery story is part of the culture that keeps capital punishment alive...While he has studiously avoided stating conclusions about the morality, wisdom, or constitutionality of capital punishment, Garland’s empirical analysis speaks to all three...I commend Peculiar Institution to participants in the political process.”—John Paul Stevens, New York Review of BooksAnd the blurbs:

“This is indispensable reading for students of criminal justice, race, and American culture, for lawyers and judges in the pathways of death, and for all who want to understand why our country can neither put capital punishment to any good use nor put an end to it.”—Anthony G. Amsterdam, University Professor and Professor of Law, New York University

“Peculiar Institution provides the best explanation I have ever read as to why the United States, alone among western democracies, retains the death penalty, and why we have the odd system we do, in which a very small percentage of the people sentenced to death are actually executed.”—Stuart Banner, author of American Property

“Peculiar Institution tells a fascinating and important story that illuminates why the death penalty is so problematic and yet so well suited to American practices.”—Austin Sarat, author of When the State Kills: Capital Punishment and the American Condition

DC Area Legal History Roundtable

The D.C. Area Legal History Roundtable is an informal gathering of law professionals and historians who live and work around Washington, D.C.

The next meeting of the Legal History Roundtable will be held March 25, 2011 and hosted by the Federal Judicial Center’s Federal Judicial History Office at the Thurgood Marshall Federal Judiciary Building in Washington D.C. (located adjacent to Union Station).

We invite papers from legal scholars and historians whose work touches on any aspect of the history of federal law or the federal judicial system. Topics may include, but are not limited to, development of court organization, federal criminal and civil jurisdiction, litigation in federal courts, the evolution of federal practice and procedure, constitutional law, or judicial biography.

For further information and to submit a paper proposal, contact Ryan Rowberry, at rrowberry@fjc.gov. The deadline for proposals is January 31, 2011.

Monday, January 24, 2011

Important New Property Casebook

illustrate the centrality of race in contemporary property and in the development of property doctrine; and cases that integrate racial minorities into the first year curriculum as litigants . . . . Our hope was that faculty and students would turn to the book as a supplement to the first year property casebook.As a teacher of first-year property (is this still the most common "bread and butter" course taught by legal historians?), I think this book is quite valuable both for its careful and subtle use of history, and the new connections it brings to light. The book also offers a highly effective and creative way into the traditional Property course, one that highlights "law in action" across U.S. history and across property doctrine. Is this book a model for how legal historians could fashion casebooks to supplement other first-year courses? Or is Property in this case unique? Here is Al's description from The Faculty Lounge:

Integrating Spaces

I'll take advantage of the fact that I'm snow bound to talk about something that I've been meaning to blog about for a few weeks: Integrating Spaces: Property Law and Race, which is a supplemental property casebook that Alberto Lopez, Kali Murray, and I have put together. Aspen mailed copies to likely adopters (that is first year property professors) at the end of November.

We had a couple of goals in mind for Integrating Spaces -- we wanted to have some new cases that teach contemporary property doctrines in creative ways; cases that illustrate the centrality of race in contemporary property and in the development of property doctrine; and cases that integrate racial minorities into the first year curriculum as litigants even when race at issue. Our hope was that faculty and students would turn to the book as a supplement to the first year property casebook.Kim was kind enough to talk about one of our cases earlier this semester -- it's the Hershey Trust case, which actually has nothing to do with race; we included it because it dealt with a theme we develop in various places -- drawing a line between private property rights and "community" rights.I know I'm incredibly biased -- but there are a lot of really cool cases in Integrating Spaces. One of them, for instance, is United States v. Platt -- about a prescriptive easement that the United States asserted on behalf of the Zuni people who wanted to cross land that their ancestors had been crossing for at least as long as Europeans had been in the Americas, to reach a holy place, Kolhu/wala:wa, also known as "Zuni Heaven." (I have used one of John Hillers' late nineteenth century photographs of a Zuni pueblo in New Mexico to illustrate this.) What I really like about this case is -- first it's darn interesting -- and second you can do a lot with figuring out why the US is able to establish a prescriptive easement (the evidence that's used, including motion pictures from the 1920s) of the pilgrimage -- but also there are questions about why the landowner who had recently acquired the property took it subject to the easement.

We also have a couple of cases on partition by sale (or partition in kind), running from states that are quite permissive in partition by sale (like Arkansas) and those that are substantially more stringent (like Hawaii). Later I hope to talk some more about this and some of the other contemporary cases, like a Colorado case, Labato v. Taylor, that established an easement for pasturing animals that had been exercised since the land was acquired from Mexico -- which gives a way of reviewing the differences between easements by implication, by estoppel, and by prescription.I also want to talk later about a case from Texas in the 1920s that found a jazz club in San Antonio (the Silver Leaf Club) to be a nuisance and another case from South Carolina that found an African American church in Columbia (the United House of Prayer) to be a nuisance. That case -- which discusses the difference between Columbia's attempted ordinance to declare the House of Prayer a nuisance and the later judicial finding that it was a nuisance -- goes well with the Smithsonian's CD of music from the House of Prayer. You can listen to a sample of a sample of the CD here.

It's my hope (and I'm certain Aspen's as well) that lots of property professors will adopt this as a supplemental text for their first year classes -- but as an interim move, I hope that they'll teach some of the cases from it and see how they go. I'm pretty sure the students will like the cases; at least that's my experience from the last couple of years where I've taught much of the book to my first years.

CFP: Bench and Bar: The (Dis)appearance of Britain

CALL FOR PAPERS

Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly

Special Issue: Bench and Bar: The (Dis)appearance of Britain

We are compiling a Special Issue for the Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly (NILQ) on the topic of ‘Bench and Bar: The (Dis)appearance of Britain’. We wish to invite scholars with an interest in this broad theme to submit abstracts of around 250 words by Monday 28 February 2011. We will make a provisional selection in early March 2011 and then ask contributors to provide a full draft of their text by Wednesday 15 July 2011. These will then be refereed blind in the usual way. Final articles accepted for publication should be with the NILQ by December 2011 for publication in the first volume of 2012.

As the British Empire extended its reach during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Western (specifically British) concepts of law and justice were exported around the world. As the empire retracted in the twentieth century, a residual legal order was left in its wake: the common law. In many colonies and British territories, the early twentieth century was a time of uncertainty. As the roles of the imperial parliament and the judicial committee of the Privy Council changed, national legal systems began to emerge.

This Special Issue of the Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly seeks to address some of the issues which have arisen as a consequence of the (dis)appearance of British Imperialism.

Suggested topics include (but are not limited to): The role of national courts and legislatures in shaping ‘new’ legal orders How tension between old and new orders was resolved How the judiciary and legal community responded to the abolition of Privy Council appeals The role of law in the formation of new states How former colonies and dominions have diverged in their interpretation and development of common law principles The role of lawyers and legal professions in the transition from imperialism to independence Whether British systems of law and justice continue to exert influence over the legal systems of its former territories; and whether lawmakers in former colonies have looked and continue to look towards Britain for guidance The Bench and Bar in the UK and the colonies, for example:

o How was the English model exported?

o The extent to which the English model is still used?

o Whether ex-colonies made changes to their legal professions in the aftermath of independence?

o The influence of individuals who migrated from the English bar to the colonial bars?

Please send abstracts via email attachment to:

Dr Karen Brennan, Queen’s University of Belfast, School of Law,

Dr Niamh Howlin, Queen’s University of Belfast, School of Law,

Dr Sara Ramshaw, Queen’s University of Belfast, School of Law.

Tiersma on Language Policy in the United States

Peter Tiersma (Loyola, Los Angeles) has posted a chapter of The Oxford Handbook on Language and Law (forthcoming 2011), which he is co-editing with Lawrence Solan (Brooklyn Law School).

Peter Tiersma (Loyola, Los Angeles) has posted a chapter of The Oxford Handbook on Language and Law (forthcoming 2011), which he is co-editing with Lawrence Solan (Brooklyn Law School).The chapter

contains an overview of language policy in the United States, starting in the early days of the republic, the attempts to force Native Americans to assimilate culturally and linguistically to the dominant English-speaking American culture, the nativist movement around World War I, and the more recent efforts to make English the official language of the United States and of individual states. More specifically, it discusses the constitutionality of Official English (or English-only) laws and ends with a brief survey of rights of limited English speakers to social services in their own languages and to have their children receive bilingual education.You can download it here.

Hat tip: bookforum

Tirres on Immigrants and the Law in American History

Image credit.This essay will appear in the forthcoming Blackwell Companion to American Legal History. The essay explores the major works and themes in the history of U.S. immigration law, including attention to the histories of immigrants themselves. One of the challenges, and opportunities, of studying immigrants and the history of immigration law is grappling with the contradictions and inconsistencies of this politically-charged category. Immigration law is a window onto American perceptions of national identity. According to the classic formulation, the U.S. is a "nation of immigrants," its past and future tied inextricably to the waves of migrants who came, and continue to come, to its shores seeking the mythical "American Dream." Yet alongside that mythical, constitutive story of inclusion is an equally strong story of exclusion, more often than not along lines of race, class, and political ideology. Law has played a pivotal role in both these stories, serving alternately as a mechanism for drawing in immigrants and as a tool for excluding and marginalizing them. Law has been, and continues to be, central in shaping and defining the immigrant experience in the United States. This essay seeks both to explain the general trends over time in immigration law as well as to introduce the reader to the seminal texts in the field. It is divided into four main sections which proceed in rough chronological order, each exploring the major secondary literature and themes for that particular time period.

Sunday, January 23, 2011

Thurgood Marshall's Letters, Brinkley on Alaska, and more in the book pages

Thurgood Marshall the NAACP lawyer comes across in his letters as an advocate of unflagging commitment with a fighting spirit. He advised a Texas NAACP leader that the Dixiecrats who upheld segregation could only be defeated by “hitting back at them every time we can in every way we can.’’ In a 1940 report from Birmingham, Ala., to his boss, White, Marshall concluded, using the language of the day, “I’m all for these Negroes down here. They want to fight.’’The rest is here.

The Quiet World: Saving Alaska's Wilderness Kingdom 1879-1960 by Douglas Brinkley gets a mixed review from Geoffrey Mohan in the Los Angeles Times. He writes that the book is

But Brinkman's biographical approach "ultimately gives short shrift to Alaska as a place," so that the state "disappears for long passages that are located in the great elsewhere." Read the rest here.an exhaustively detailed account of the evolution of public policy and conservation philosophy that swirled around the 49th state from 1879, when John Muir began his eloquent prose epistles that brought "Seward's Folly" into the popular imagination, to 1960, when what now is known as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was established. It's a historical and intellectual terrain as complex and outsized as the state itself — with just as many hazards. Among them are the towering peaks of American conservation: Muir, Teddy Roosevelt, Aldo Leopold.

A STRANGE STIRRING: “The Feminine Mystique” and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s by Stephanie Coontz is taken up in the New York Times, and Revival: The Struggle for Survival Inside the Obama White House by Richard Wolffe is reviewed in the New York Review of Books.

Saturday, January 22, 2011

Weekend Roundup

- Penn's Supreme Court Clinic is working with American and English legal historians to draft a proposed amicus brief by a group of legal historians to the Supreme Court in Al-Kidd v. Ashcroft, the pending case on law-enforcement liability for pretextual use of the material witness statute to detain suspects. Legal historians interested in reading the brief and considering signing on (by January 26th) should contact Stephanos Bibas.

A new issue of Historically Speaking (the bulletin of the Historical Society) is out. It includes a forum on "Questioning the Assumptions of Academic History," as well as "Twenty Suggestions for Studying the Right Now that Studying the Right Is Trendy." You can find more info on the Historical Society blog. (image credit)

A new issue of Historically Speaking (the bulletin of the Historical Society) is out. It includes a forum on "Questioning the Assumptions of Academic History," as well as "Twenty Suggestions for Studying the Right Now that Studying the Right Is Trendy." You can find more info on the Historical Society blog. (image credit)

- Also at the Historical Society blog, a neat post by Dan Allosso on using probate records as primary sources. Read more here.

- The shooting of Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords has led to lots of musings on the history of the insanity defense. Dahlia Lithwick, writing for Slate, offers some good links here.

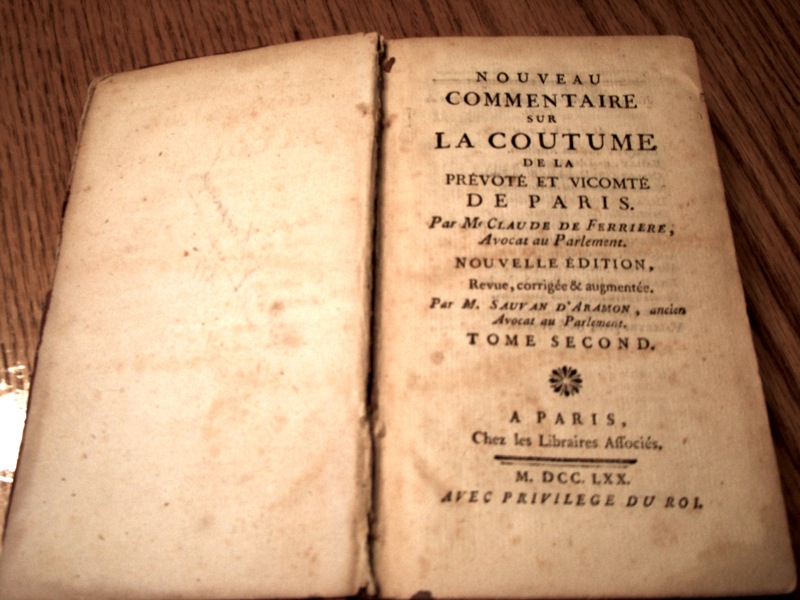

One of the law curators at the Library of Congress has put together a post spotlighting the Library's collection of coutumes, "one of the best written records of the diverse legal practices of local feudal jurisdictions." Read more at In Custodia Legis. (image credit)

One of the law curators at the Library of Congress has put together a post spotlighting the Library's collection of coutumes, "one of the best written records of the diverse legal practices of local feudal jurisdictions." Read more at In Custodia Legis. (image credit)

- At IntLawGrrls, Diane Amann notes the upcoming "Trial of Hamlet" at the University of Southern California, January 31, featuring Justice Anthony M. Kennedy (here for tickets) and suggests that the ABA should stage a mock trial based on women's legal history. A great idea, and I concur in her suggestion of the trial of Susan B. Anthony. [mld]

- People are still talking about Robert Tsai's Eloquence and Reason. We've posted a review by a legal historian and another by a first amendment scholar. Now we have one from a political scientist (Beau Breslin). You can find it here, in the most recent issue of Perspectives on Politics.

Two by Fernandez on the Antebellum U.S. Bar

This article is about a fraternal order operating in the first half of the Nineteenth Century in New York called “The Ancient and Honorable Court of Dover.” This group organized a mock trial, probably in 1834, to prosecute one of its members. A prosecutor was appointed and the President of the group gave a long speech. At issue was whether or not non-members could participate in the trial. After a description of these records and an account of their discovery, this article explains who the individuals involved in the trial were, Jacksonian politicians and lawyers with connections to the Custom House and the Tammany Society in New York City. It then describes what a “Court of Dover” was, asks about what the offence here was, and explores the connections between this group and the most famous “Ancient and Honorable” society, the Freemasons. It argues that the records of a group like this should be understood as a kind of “legal literature” that is best understood in relationship to the notion of “solemn foolery,” a phrase that has been used in connection to the legally-themed theatricals at the Inns of Court.The second is Tapping Reeve, Coverture, and America's First Legal Treatise:

Image creditIn his 1816 treatise, The Law of Baron and Wife, Tapping Reeve of Litchfield Law School fame, rejected the Blackstone/Coke maxim that a husband and wife were one person in law. This paper explains how Reeve used his book, his students, and his role as a judge to work against the principle of marital unity, for instance, causing his students to pass a statute in empowering married women to make wills. Reeve’s behavior was typical of ‘Fading Federalists,’ who losing their power in the political realm, turned to law book writing and law teaching in order to continue to press their influence. Reeve’s reasons for rejecting the one-person-in-law maxim are connected to his religion, his own marriage, and conditions that were unique to Connecticut during this period. This localism is ironic as Reeve maintained that his account was a description of English law and not anything specific to Connecticut. It is this pretense to the non-local, not avoided by his rival Zephaniah Swift, that made Reeve fit to be honored in later line-ups like Roscoe Pound’s celebration of the American ‘taught law’ textbook tradition. However, it is important to see that Reeve invoked English law as a way to challenge and contradict it, creating in effect a version of English law for America that no English lawyer would agree with. The strategy in the book was to invoke the authority of the common law while simultaneously challenging and re-creating it. What this paper shows is that the version of American common law the treatise put forward was tied very much to local conditions despite what it formally claimed and disclaimed.

Friday, January 21, 2011

Willrich on the History of Vaccine Scares in the United States

Michael Willrich, Associate Professor of History at Brandeis University, has an op-ed in The New York Times entitled “Why Parents Fear the Needle.” Willrich considers recent fears that vaccines cause autism in light of the history of vaccine scares in America. Popular resistance to vaccinations, he explains, raised important questions about the balance between public health and civil liberties in nineteenth and twentieth century America.

Read the op-ed here.

Willrich’s forthcoming book, Pox: An American History (Penguin Press) will be available in early April. Here’s the book description:

At the turn of the last century, a powerful smallpox epidemic swept the United States from coast to coast. The age-old disease spread swiftly through an increasingly interconnected American landscape: from southern tobacco plantations to the dense immigrant neighborhoods of northern cities to far-flung villages on the edges of the nascent American empire. In Pox, award-winning historian Michael Willrich offers a gripping chronicle of how the nation's continentwide fight against smallpox launched one of the most important civil liberties struggles of the twentieth century.

At the dawn of the activist Progressive era and during a moment of great optimism about modern medicine, the government responded to the deadly epidemic by calling for universal compulsory vaccination. To enforce the law, public health authorities relied on quarantines, pesthouses, and "virus squads"-corps of doctors and club-wielding police. Though these measures eventually contained the disease, they also sparked a wave of popular resistance among Americans who perceived them as a threat to their health and to their rights.

At the time, anti-vaccinationists were often dismissed as misguided cranks, but Willrich argues that they belonged to a wider legacy of American dissent that attended the rise of an increasingly powerful government. While a well-organized anti-vaccination movement sprang up during these years, many Americans resisted in subtler ways-by concealing sick family members or forging immunization certificates. Pox introduces us to memorable characters on both sides of the debate, from Henning Jacobson, a Swedish Lutheran minister whose battle against vaccination went all the way to the Supreme Court, to C. P. Wertenbaker, a federal surgeon who saw himself as a medical missionary combating a deadly-and preventable-disease.

As Willrich suggests, many of the questions first raised by the Progressive-era antivaccination movement are still with us: How far should the government go to protect us from peril? What happens when the interests of public health collide with religious beliefs and personal conscience? In Pox, Willrich delivers a riveting tale about the clash of modern medicine, civil liberties, and government power at the turn of the last century that resonates powerfully today.

Even more on lynching: McClure reviews Segrave, Lynchings of Women in the United States

Here is the first paragraph of the review, by Helen McLure (Southern Methodist University):

In Lynchings of Women in the United States, Kerry Segrave, author of short studies on such topics as vending machines, drive-in movie theaters, tipping, jukeboxes, ticket scalping, smoking, and American women and capital punishment, presents an equally brief précis of the extrajudicial execution of women in U.S. history. Segrave’s work is important because it addresses a major gap in the literature of this topic, as it is only the second published study of the lynching of American women and the first to attempt to chronicle these collective killings on a national scale. The book proceeds in a chronological fashion and consists of summaries of ninety-seven lynching cases based on nineteenth- and twentieth-century newspaper reports. Several of these cases have not been previously documented by lynching scholars, and this new information, when adequately sourced, constitutes one of the book’s major contributions to the scholarship. However, Segrave’s inclusion in this compilation of several completely unsourced, unconfirmed cases from the Web site autopsis.org also suggests using considerable caution regarding some of these alleged incidents. The case summaries are based on contemporary newspaper reports and flesh out the stark details of most of the previously known cases, and the collection serves as a valuable and convenient reference and starting point for more serious research and analysis. This book should be most useful to historians of American crime, lynching, and mob violence; the American South; and women’s and gender history; as well as a wider audience of the reading public interested in crime and violence in U.S. history.You can access the full review here.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

At Common-place: Connolly on Transnationality in Early American History; Chu Reviews LaCroix, “The Ideological Origins of American Federalism”

For those interested in some of the questions about international history that I raised in an earlier post, the January issue of Common-place features an article by Brian Connolly calling for critical analysis of transnationality in the history of early America. In, “Intimate Atlantics” Connolly asks: “If we turn to the transnational as a critical frame in order to expose the fragility of the nation, where do we turn to the expose the fragility of the transnational?” He writes:

The desire for ever larger geographic scales as arbiters of historical truth should be apparent to anyone working in early American studies over the last two decades. The scholar working on a community, town, or city study is questioned on its relevance to the region. Those working on regions or towns are asked about their relevance to the nation. Those working on the nation find themselves fielding questions about the Atlantic, the hemispheric, or the transnational. Those working on the Atlantic, hemispheric, or transnational arenas are questioned on the scale of the global. Those working on the global … well, I guess the astronomical is next. To put it more pointedly, would moving forward to the universe be a return to the universal?

Common-place also has a review of Alison LaCroix, The Ideological Origins of American Federalism by Jonathan Chu. Chu writes:

The Ideological Origins of American Federalism is an important work that points out the necessity of seeing Revolutionary developments in a larger context. In so doing it also makes three important specific contributions.It demonstrates how the arguments supporting opposition to British tax policies evolved into ideological and constitutional innovation. Second, in assessing the ideological legacies of the American Revolution, it compels us to reconsider Federalist history—our tendency to assume that the Constitution was simply the repudiation of a set of failed structures and intellectual paradigms and was the starting point for subsequent constitutional analysis. And third, like Jack Rakove's Original Meanings, it should give most serious pause to those who assume that the original intentions of the founders are easily discerned.

Read the rest of the review here.

Mirow on The Constitution of Cadiz (1912) in Historical and Constitutional Thought

This chapter examines the ways the Spanish Constitution of 1812, also known as the Constitution of Cadiz, has been viewed in historical and constitutional thought. The document is a liberal constitution establishing constitutional rights, a representative government, and a parliamentary monarchy. It influenced ideas of American equality within the Spanish Empire, and its traces are observed in the the process of Latin American independence. To these accepted views, one must add that the Constitution was a lost moment in Latin American constitutional development. By the immediate politicization of constitutionalism after 1812, the document marks the beginning of constitutional difficulties in the region.

This chapter has sections addressing: national sovereignty and popular representation, historical justification in the Cadiz process, liberal constitutionalism and constitutional rights, American equality and independence, and the politicization of constitutional texts and processes.

Harris reviews Vile, Pederson, Williams, eds., "James Madison: Philosopher, Founder, and Statesman"

Via H-Law, we have a review of James Madison: Philosopher, Founder, and Statesman (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2008), a collection of essays edited by John R. Vile (Middle Tennessee State University), William D. Pederson (Louisiana State University), and Frank J. Williams (former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island).

Via H-Law, we have a review of James Madison: Philosopher, Founder, and Statesman (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2008), a collection of essays edited by John R. Vile (Middle Tennessee State University), William D. Pederson (Louisiana State University), and Frank J. Williams (former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island).Here's an excerpt from the review, by Matt Harris:

The essays, though not of equal quality, cover Madison the “Philosopher, Founder, and Statesman,” which is the subtitle of the book. It is divided into six sections spanning a range of topics including Madison’s intellectual influences, Madison’s constitutional contributions, Madison and religious freedom, Madison as president and party leader, and Madison and the Supreme Court. Though some of the essays lack originality and insight, they offer a trenchant insight into why Madison is important “for understanding the American experiment in constitutional government” (p. vii).Harris concludes that, taken together, the essays

provide a rich and nuanced look at Madison’s life and legacy. In addition, they suggest new lines of inquiry for scholars to pursue. Finally, they force us to grapple with the editors’ claim that Madison was indeed primus inter pares among his countrymen with respect to liberty under law, freedom of conscience, and for “understanding the American experiment in constitutional government” (p. vii).You can read the full review here.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Lanni on Transitional Justice in Ancient Athens

This article presents our first well-documented example of a self-conscious transitional justice policy - the classical Athenians’ response to atrocities committed during the reign of the Thirty Tyrants - as a case study that can offer insight into the design of modern transitional justice institutions. The Athenians carefully balanced retribution and forgiveness: an amnesty protected collaborators from direct prosecution, but in practice private citizens could indirectly sanction even low-level oligarchic sympathizers by raising their collaboration as character evidence in unrelated lawsuits. They also balanced remembering and forgetting: discussion of the civil war in the courts memorialized the atrocities committed during the tyranny, but also whitewashed the widespread collaboration by ordinary citizens, depicting the majority of the populace as members of the democratic resistance. This case study of Athens’ successful reconciliation offers new insight into contemporary transitional justice debates. The Athenian experience suggests that the current focus on uncovering the truth may be misguided. The Athenian case also counsels that providing an avenue for individual victims to pursue local grievances can help minimize the impunity gap created by the inevitably selective nature of transitional justice.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Nineteenth-Century International Law: Becker Lorca, Oszu, and Gozzi in the Harvard ILJ

The Harvard International Law Journal has a fascinating exchange on Nineteenth-Century International Law. In “Universal International Law: Nineteenth-Century Histories of Imposition and Appropriation,” Arnulf Becker Lorca challenges the notion that international law became universal through a unilateral process of European expansion. Rather, he argues, international law became universal during the nineteenth century as semi-peripheral jurists appropriated and reinterpreted international law to include non-Western sovereigns.

According to Becker Lorca, “a generation of non-Western international lawyers studied European international law with not only the purpose of learning how to play by the new rules of international law that Western powers sought to impose on them, but also with the aim of changing the content of those rules” (482). As Becker Lorca shows, non-Western jurists successfully reshaped some of the central elements of the European law of nations, namely, positivism, the standard of civilization, and absolute sovereignty “to advocate for a change in extant rules of international law and to justify the extension of the privileges of formal equality to their own states in their interactions with Western powers (482-483).”

Becker Lorca's article points up the enduring question of the tension between imposition and appropriation of Western legal norms in the nineteenth century. While his argument focuses on the development of nineteenth century international law, its central issues are relevant, more broadly, to legal historians working to understand the movement of laws and legal norms between Western and non-Western legal experts either under conditions of formal colonial rule, unequal treaty relations, or informal imperial rule in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

You can download the complete exchange, including a response from Gustavo Gozzi, “The Particularistic Universalism of International-Law in the Nineteenth Century,” at the website of the Harvard International Law Journal.