|

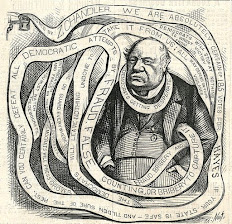

David Dudley Field (Harper's Weekly; NYPL)

|

[Guest Blogger

Michael S. Ariens's posts on his new book,

The Lawyer's Conscience, continues. DRE]

A notice printed in the December 16, 1870 issue of the

New York Times titled

James Fisk's Lawyers discussed the general retainer agreement between Fisk and the law firm of Field and Shearman, headed by David Dudley Field. The

Times reported and rejected the firm's claim that "it was the duty of the advocate to accept all cases offered him." Ten days later, the Times reprinted stories from two other newspapers about Field and Shearman's decision to take a general retainer from Fisk. One of the two simply reprinted the December 16

Times article, which gave the Times another opportunity to criticize the firm's claim that it was duty-bound to represent any client wishing to hire it. The second article came from the December 7, 1870 issue of Samuel Bowles' Springfield Massachusetts

Republican. That article quoted a letter from a young, unnamed New York lawyer, who like Field, was raised in western Massachusetts. The letter accused Field of receiving more than $200,000 in legal fees for his work for the Erie Railway and its principal owners, Fisk and Jay Gould. Though remunerative, the writer claimed Field had "destroyed his reputation as a high-toned lawyer with the public," and "lawyers disliked him for his avarice and meanness." Finally, the correspondent claimed the late and revered New York lawyer James T. Brady had once accused Field of being "'the king of the pettifoggers,' which title has stuck to Field ever since."

Field was then 65 years old. He was well known, both for his legal talents and his antebellum work as a legal reformer. He also seemed compelled to respond to any criticism from anyone. Field sent a letter to Bowles asking that he publicly disavow the contents of the letter. Bowles refused. They, joined by Field's son Dudley Field, continued a correspondence soon published in pamphlet form.

By the end of 1870, Field had represented Fisk, Gould, and the Erie for almost three years. He had just agreed to defend the notorious Tammany Hall leader William "Boss" Tweed against criminal charges. And public criticisms of his professional behavior had just begun. When initially representing the Erie, Field had accused Judge George G. Barnard of unlawfully conspiring with America's wealthiest person, Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt, to take control of the Erie. After that Erie "war" was settled, Field and his clients had a rapprochement with Barnard, first absolving him of any corrupt wrongdoing in concert with Vanderbilt (Barnard had also been accused of taking bribes, in his own court, by James Brady-Barnard neither denied it nor castigated Brady for his accusation, and Barnard had been accused of corruption by Field's partner Thomas Shearman even earlier). Now Barnard issued injunctions in favor of the Erie at the faintest whisper from its lawyers, including Field.

In the third of the four Erie "wars," Field represented the Erie in its attempted takeover of the Albany & Susquehanna (A&S) railroad. Barnard issued an arrest warrant for the officers of the A&S at the request of Field and Shearman, which included arresting A&S lawyer Henry Smith, making it impossible for him to defend the interests of A&S. Another judge, later assessing this extraordinary event, concluded the Erie's lawyers had "fraudulently procured an order for [their] arrest."

Bowles's criticisms were soon followed in an unsigned, three-part article in

The Nation, lawyer Francis C. Barlow soon revealed himself as its author. The

New York Tribune criticized Field in a January 31, 1871 article, and Barlow wrote letters to its editor published on March 7-9, quickly followed by a pamphlet,

Facts for Mr. Field. The

North American Review published two articles criticizing Field's conduct, one by Albert Stickney and the other by Charles Francis Adams, both of whom attempted to answer Field's question, what specific professional misconduct did I engage in? Those articles caused the Boston-based

American Law Review, edited by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Arthur Sedgwick, to opine that the Association of the Bar of the City of New York (ABCNY) investigate and, if necessary, disbar Field.

Field and his defenders responded to every criticism. A common response was that Field was improperly tarred with the "bad motives" of his clients. He was simply doing what every good lawyer should do: "everything for his client that he can honestly do." Though the Field fracas was in abeyance for the rest of 1871, successful anticorruption efforts in New York made reformers ascendant and Field on the defensive. The ABCNY began investigating Judge Barnard and two other judges who were believed in the Erie's pocket, Albert Cardozo (father of Benjamin) and John McCunn. Field's accuser Albert Stickney aided the state Assembly's impeachment investigation, in part by sharply cross-examining Field. Cardozo resigned from office, McCunn died three days after he was convicted, and Barnard was convicted and removed from office in August 1872. He was convicted of twenty-five articles of impeachment, including all related to the Erie wars.

The conviction of Barnard may have emboldened Stickney, who renewed his condemnation of Field's behavior, publishing them in

Galaxy. At the same time, he, joined by two fellow Barnard prosecutors, proposed the ABCNY's judiciary committee make recommendations concerning the lawyers connected with Barnard, Cardozo, and McCunn, meaning David Dudley Field, Dudley Field, and Thomas Shearman. In an extraordinary meeting in December 1872, Field demanded he be tried immediately and be either expelled or cleared. Much of Field's defense (as published the next day, for he was unable to read the entire speech at the meeting) consisted of

ad hominem attacks on Stickney (who sought "the little newspaper notoriety that he has coveted, begged and earned") and other accusers. Field also defended his actions by pointing to letters of support written by twelve lawyers and judges who, at Field's behest, assessed whether he acted unprofessionally or improperly. Several relied on the absence of evidence that Field possessed "knowledge" of Barnard's corruption to justify Field's actions.

The December meeting ended with no one satisfied. Field's demand was postponed for a month; when the ABCNY next met, the judiciary committee washed its hands of the matter. No action against Field would be taken.

Field lived for another twenty years, dying in 1894. The treasurer of the ABCNY informed its executive committee of Field's death. Ordinarily, the ABCNY would commission work on Field's memorial. Instead, it decided not to mention Field or commemorate his life "in any way."

Late medieval societies witnessed the emergence of a particular form of socio-legal practice and logic, focused on the law court and its legal process. In a context of legal pluralism, courts tried to carve out their own position by influencing people’s conception of what justice was and how one was supposed to achieve it. These “scripts of justice” took shape through a range of media, including texts, speech, embodied activities and the spaces used to perform all these. Looking beyond traditional historiographical narratives of state building or the professionalization of law, this book argues that the development of law courts was grounded in changing forms of multimedial interaction between those who sought justice and those who claimed to provide it. Through a comparative study of three markedly different types of courts, it involves both local contexts and broader developments in tracing the communication strategies of these late medieval claimants to socio-legal authority.