In my final post, I

want to end with a plea, or better yet, a pitch. Use local court records, in

your research and your teaching, and if you have the power to do so, help

preserve them. These records are important for the stories they tell and the

voices they feature.

In terms of my own research interests, the extant cases

reveal a previously unknown world of black legal activity. In these records,

you find the story of Milly, an enslaved Mississippi woman who sued a white man

for sizable debts he that owed her. She won, even though she didn’t have the

standing to initiate the suit in the first place. You will also meet

Franchette, a free woman of color who sued Isabella Hawkins (a free black woman

and former slave) three times to recover stolen property. In these lawsuits,

Franchette accused Hawkins of stealing her cows and branding them with the

letters “IH,” and in all three cases the court ordered Hawkins to return the

cattle and pay Franchette damages.

|

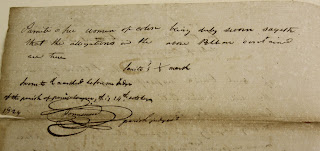

| Photo by the author |

Hawkins

herself was no stranger to the courtroom, although most often she did the

suing. For instance, in 1834, Hawkins sued Frederick Haydt, a white man, for

stealing her horse and attempting to sell it. The court ordered that Haydt

return the horse. She even successfully sued the local sheriff after he seized

her slave to settle a debt incurred by her former owner. She initiated this

lawsuit against the sheriff only a few short years after her manumission. In

addition, you see hundreds of enslaved people suing slaveholders for their

freedom and claiming ownership over their bodies and their labor. In their suits

for freedom, they also made claims to property they held as slaves and expected

the court to help them safeguard it. They also demanded (and received) back

wages, compensation for their unpaid labor.

|

| Photo by the author |

But there are other things you can

see as well. Because these records document the everyday workings of the court

system in local communities, it was ordinary people who used them. Many of them

were poor or living on the margins—people who, unlike wealthy planters, left

few records about their lives behind. Many were illiterate, for instance, so

they didn’t keep diaries or account books. As social historians and scholars of

race and gender have long shown, court records provide some insight into the

lives of those whose voices we may not have otherwise heard. Indeed, in some

cases these are the only records we have that document the lives of non-elites.

You also see married women—black and

white—using the courts to their own advantage. This too might seem surprising,

because in the early 19th century married women in the U.S. lacked a legal

personality. Once they married, they forfeited their legal rights. Yet, they

were present in the local legal record of Mississippi and Louisiana (and

elsewhere), acting at law in their own names and making contracts and suing to

enforce them. They also sued their own husbands for mismanaging their property

or for damages for abuse. In other instances, they sued their husbands for

divorce. Indeed, local court records show married women playing fast and loose with

the doctrine of coverture, ignoring it when convenient and using it when it

benefited them.

You might find interesting anecdotes

to tell your friends or new insults to hurl at your enemies. For instance, you

could tell them about a Mississippi man who was charged with using deception to

obtain a set of false teeth, or a Louisiana man who ran naked through a theater

with ladies present and then stripped off his pants in court while the judge

read the charges against him. Defamation lawsuits are full of great insults:

like one of my favorites, “grasshopper from hell.”

|

| Photo by the author |

In

using these records, you might even reach an audience outside of academia. For

instance, right after the publication of my book, a descendant of one of the

formerly enslaved litigants I wrote about emailed me. She found her family

member in my index (his name came up in Google Books in an internet search),

and she contacted me for more information about him and other members of her

extended family. I have also been lucky enough to meet several descendants of

the Belly/Ricard family, a family I discuss in a chapter-long case study at the

end of my book.

In addition, these records make

great teaching tools. I refer to the insights I have gained from reading them

in my lectures, and I make them available to my undergraduate students for use

in our class discussions (in classes that range from women’s and gender history

to legal history to the history of U.S. slavery). I also provide copies for both

undergraduate and graduate students interested in a wide range of research

topics. As I tell my students each time I teach with them, you should work with these types of records not only

because you might enjoy being a voyeur or at least a witness to everyday life,

but also because they demand a particular set of skills. They teach us how to

figure out a complex social landscape and how to think more robustly about

power; and they teach us how organizations work on the ground (rather than how

organizations think they work). In other words, working with

trial court records makes us attentive to what people value and the lengths

they are willing to go to in order to protect those things. Such skills are

valuable to the history major, but also beyond.

|

| Photo by the author |

Thanks again to the editors for the invitation to guest blog. Readers, there are copies of representative cases on my website (kimberlywelch.net). And if you have any questions about Black Litigants in the Antebellum American South or want to talk about accessing, using, or preserving local courts records, please get in touch.