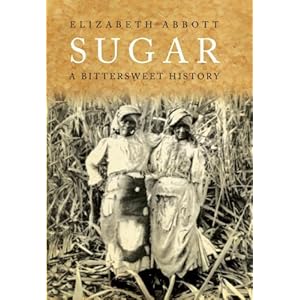

wait his book, Elizabeth Abbot has published SUGAR: A Bittersweet History, reviewed today in the New York Times.

wait his book, Elizabeth Abbot has published SUGAR: A Bittersweet History, reviewed today in the New York Times.“A hundred years before Pushkin described ecstasy as ‘a glassful of tea and a piece of sugar in the mouth,’ the demands of the sugar economy had ripped apart African communities and forced slaves across the Atlantic to work sugar cane plantations,” writes reviewer Isaac Chotiner. Though he views the author’s argument about sugar’s role in slavery to be too broad, he notes that “Abbott's book, which discusses the effects of sugar on everything from the Haitian revolution to Hitler's Germany, serves as a grim reminder that a consumer's choices register on a gigantic scale, and are therefore as much political as personal.”

Continue reading here.

Meanwhile, Will

iam Rosen takes up another transnational topic: the history of steam power in The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry, and Invention. Jeff Vandermeer writes for the Los Angeles Times that Rosen “makes interesting, even exciting, such subjects as patent law from the Roman Tiberius on, technological innovation in ancient China and the role of practice in separating out accomplished performers from the ‘merely good.’” There seems to be much law in this story. Vandermeer continues:

iam Rosen takes up another transnational topic: the history of steam power in The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry, and Invention. Jeff Vandermeer writes for the Los Angeles Times that Rosen “makes interesting, even exciting, such subjects as patent law from the Roman Tiberius on, technological innovation in ancient China and the role of practice in separating out accomplished performers from the ‘merely good.’” There seems to be much law in this story. Vandermeer continues:Rosen's central thesis is that the Industrial Revolution started specifically in Britain, despite a number of false starts elsewhere, due not just to a wealth of the necessary raw materials - a situation found elsewhere in the world - but also to such factors as a change from a patronage system for inventors to one that recognized intellectual property rights. Rosen further argues that the steam engine was "the signature gadget of the Industrial Revolution." Why? "Its central position connecting the era's technological and economic innovations: the hubs through which the spokes of coal, iron, and cotton were linked."Continue reading here.

The history of another technology, BRILLIANT: The Evolution of Artificial Light by Jane Brox is reviewed this week in the Washington Post. Joshua Glenn writes

:

:Until the 18th century, night was an impenetrable abyss. Tallow candles, made of rendered animal fat, barely lightened the darkness. The workday was tied to the sun; once you could no longer see your work, labor stopped. Then tallow candles began to be replaced by whale spermaceti candles, which were twice as brilliant, and by lamps that burned cheap and abundant whale oil. Small wonder that this era was later dubbed the Age of Enlightenment....Read the rest here.

But, Jane Brox asks, at what cost? Though she celebrates human ingenuity and technical advances in "Brilliant," her history of artificial light, Brox also presents damning evidence that in our millennia-long quest for ever more and brighter light, we've despoiled the natural world, abandoned our self-sufficiency and trained ourselves to sleep and dream less while working more.

Also reviewed this week: THE SULTAN'S SHADOW: One Family's Rule at the Crossroads of East and West by Christiane Bird in the Washington Post; A Short History of the Jews by Michael Brenner in the New Republic’s The Book; HIGH FINANCIER: The Lives and Time of: Siegmund Warburg by Niall Ferguson in the Washington Post; Golden Gate: The Life and Times of America's Greatest Bridge by Kevin Starr and Colossus: Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century by Michael Hiltzik are reviewed in the Los Angeles Times; YOUNG ROMANTICS: The Tangled Lives of English Poetry’s Greatest Generation by Daisy Hay in the New York Times.