This post, by Karen Tani (University of Pennsylvania), is the fifth in a series of posts in which legal historians reflect on Outside In: The Oral History of Guido Calabresi (Oxford University Press), by Norman I. Silber.

In three earlier posts in this series (here, here, and here), I suggested the fruitfulness of placing Guido Calabresi’s life alongside the rise of what sociologist Elizabeth Popp Berman has called “the economic style of reasoning”—an approach to governance that flourished in the later decades of the twentieth century and has now become embedded in institutions (e.g., the Congressional Budget Office) and in law (e.g., the consumer welfare standard in antitrust law, executive orders mandating cost-benefit analysis of proposed regulations). [All the Berman quotes in what follows are from Thinking Like an Economist: How Efficiency Replaced Equality in U.S. Public Policy (Princeton University Press, 2022) (“TLE”).] This rise to prominence merits our attention, Berman argues, because, over time, it narrowed the boundaries of what is politically possible, in domains ranging from environmental policy, to social welfare provision, to the governance of regulated industries. It did so by de-legitimizing or crowding out political claims that conflicted with those of the “economic style,” including “claims grounded in values of rights, universalism, equity, and limiting corporate power” (TLE 4). The result, in Berman's assessment, was to reinforce a “conservative turn” in American politics--even though “the most important advocates for the economic style in governance consistently came from the center-left” (TLE 13, 19). (For the fullest and most careful explanation of the argument, please read the book!)

In my previous posts, I argued that Calabresi’s scholarship has resonances with “the economic style,” but also sits outside of it. The insider/outsider character of Calabresi's work was a natural outgrowth of his unique path into Law & Economics. It also reflects his real-time reactions to the success of Law & Economics. As he helped that field expand and thrive, he also felt compelled to point out the limitations of economic theory and methodology. The question I ended my last post with was: Did Calabresi’s nuanced approach to Law & Economics help legitimize and spread the less nuanced “economic style” of Berman’s concern? Or (and?) did his work plant seeds of skepticism and resistance?

A historian cannot answer this question with any certainty (especially not in a short blog post!), but I will surface some evidence that seems relevant to me. In doing so, I must also acknowledge my affection for the subject of this post (I was one of Calabresi’s law clerks in 2007-08 and cherish that experience). That relationship colors my views, but also, I hope, gives me insight. In what follows, I’ll discuss (1) scholarship (which I’ll bundle with teaching), (2) judicial decisions, and (3) network.

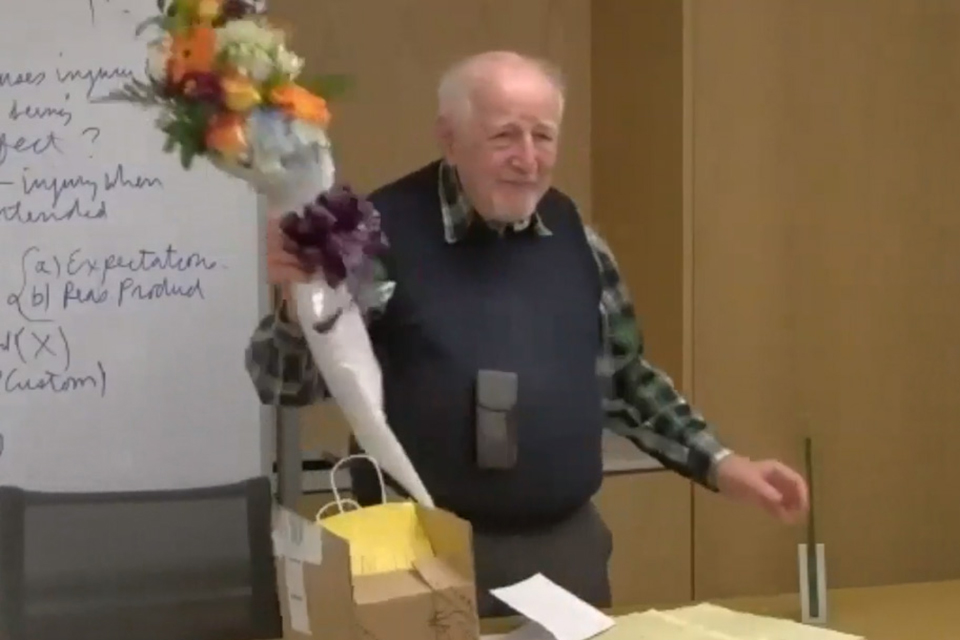

|

| "Guido Calabresi Lauded at His Final Torts Class" |

I’ve already discussed some of Calabresi’s most important scholarly writings, so I won’t repeat myself here. I’ll simply add this brief assessment. His writings—which informed six decades(!) of teaching at Yale Law School—undoubtedly did give some people their first exposure to the use of economic thinking in law and governance. That matters. Among the consumers of Calabresi’s ideas were powerful people in politics, policymaking, legal practice, and academia, as well as people who would become powerful in those domains later in life. Moreover, I suspect that Calabresi’s stature, reputation, and charisma gave weight to his ideas. In The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement, Steve Teles also credits Calabresi with giving Law & Economics respectability, by rebutting the notion “that it was an entirely conservative, University of Chicago project” (Teles 99).

That said, it difficult to gauge the precise nature of Calabresi’s influence, because his writings are open to multiple interpretations. A person enthused by “the economic style” might focus on those facets of Calabresi’s writings and teaching that enabled them to understand and apply insights from economics, such as how to use law to make the most efficient use of available resources. A person who was more skeptical of “the economic style” might feel equally validated. They might find in Calabresi’s writings the inspiration to explore whether efficiency is biased, for example, or whether regulatory uses of cost-benefit analysis adequately address distributional concerns (as a growing number of scholars are asking). Or they might seek out a different “view of the cathedral” altogether.Another way to think about Calabresi’s contribution to the spread of the “economic style” is to look at what he did when he became a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Here, the narrative in Outside In suggests at most a loose relationship between Calabresi’s Law & Economics work and his judicial decisionmaking. There were times when Calabresi did draw explicitly on his economics expertise, according to Outside In, such as in the respondeat superior case Taber v. Maine, 67 F.3d 1029 (2d Cir. 1995). (Basically, the case allowed him to make an important point about the function of respondeat superior: any enterprise carries with it certain risks, and when such a risk materializes, we ought to make the enterprise internalize the costs.) But Calabresi resisted the notion that he had used the occasion to embed his own views into law. Here’s Calabresi recounting an exchange with Richard Posner (then on the Seventh Circuit) in the wake of Taber:*

Amusingly, as soon as the opinion was released I received a note from Dick Posner telling me how wonderful he thought the opinion was, and what fun it was occasionally to be able to make one’s views the law. I didn’t think I had done that—I thought I had just clarified the law!(OI, v.2, 1999)

Elsewhere, Outside In shows that Calabresi took pains to respect that line – between what he thought the law should be and what it actually was. An example is Ciraolo v. City of New York, 216 F.3d 236 (2d Cir. 2000), where Calabresi’s opinion for the court adhered to a Supreme Court precedent that required reversal of a punitive damages award. Calabresi used a separate concurrence to air his own views on the correctness of this precedent: he explained that in the absence of punitive (or “extra-compensatory” damages), actors whom we want to deter from wrongdoing may not bear the full cost of their activities and so may not be adequately deterred. (Anthony Sebok offers a fuller discussion of Calabresi's concurrence here.)

But Outside In was never intended to be a full canvassing of Calabresi’s judicial record, and there is more to say regarding how insights from economics made their way into his opinions. One case that comes to mind for me, because of my current research on disability law, is Borkowski v. Valley Central School District, 563 F.3d 131 (2d Cir. 1995).

In brief, this case involved a teacher who had been denied tenure; she sued the school district, alleging that the decision represented discrimination on the basis of disability, in violation of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (an anti-discrimination mandate that resembles the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and has been interpreted similarly, but is limited to recipients of federal funds). The district court had granted summary judgment for the defendant school district and Borkowski had appealed.

The three-judge panel from the Second Circuit vacated the district court decision and remanded for further consideration – a move that will be familiar to many of Calabresi’s law clerks. My personal sense is that although Calabresi could appreciate the extraordinary case-management burdens that lower court judges faced, he sometimes worried that they were too quick to dispose of types of cases that they saw a lot of. When it came to antidiscrimination claims, he seemed to want to make sure that individual plaintiffs received as full and fair of a consideration as the legal system entitled them. (One might connect this to an anecdote in Outside In, involving one of Calabresi’s adult daughters, where Calabresi shows awareness of the underenforcement of antidiscrimination laws (OI, v.2, 248).)

In any event, the outcome of the case looks “liberal” in that it kept Borkowski’s claim alive and also instructed the district court to apply Section 504 in a more generous way than it had done so. Basically, Calabresi’s opinion told the lower court that it had missed a crucial step in the analysis when it had failed to consider whether there existed a “reasonable accommodation” for Borkowski’s disability that would have allowed her to meet the essential requirements of her job and thereby satisfy the tenure standard. (There’s more to say here about how the opinion clarified a muddled area, but I’ll move on.)

If the outcome of the case was “liberal,” however, it was also a vehicle for economic understandings of law. Borkowski’s discussion of “reasonable accommodation” begins by noting that the word “reasonable” does not appear in the text of Section 504, a famously spare provision. It comes from the implementing regulations, which itself define the term only by example.** In other words, the word “reasonable” for purposes of Section 504 is not unlike the word “reasonable” in Tort law. It has little predetermined content and is open to interpretation.

In the face of this openness, Borkowski defined “reasonable” as follows:

“Reasonable” is a relational term: it evaluates the desirability of a particular accommodation according to the consequences that the accommodation will produce. This requires an inquiry not only into the benefits of the accommodation but into its costs as well. See Vande Zande v. Wisconsin Dep't of Admin., 44 F.3d 538, 542 (7th Cir.1995). We would not, for example, require an employer to make a multi-million dollar modification for the benefit of a single individual with a disability, even if the proposed modification would allow that individual to perform the essential functions of a job that she sought. In spite of its effectiveness, the proposed modification would be unreasonable because of its excessive costs. In short, an accommodation is reasonable only if its costs are not clearly disproportionate to the benefits that it will produce.

Borkowski, 63 F.3d at 138.

|

| Richard Posner (credit) |

This explanation might sound, well, reasonable, especially because it doesn’t require any rigid calculation or suggest that the benefits must outweigh the costs. But with the distance of time, it’s worth noting a few things --

Vande Zande, an ADA case, was authored by Richard Posner, of the “Chicago school” of Law & Economics. As I have mentioned, Calabresi and Posner often disagreed, with Calabresi critiquing Posner for essentially pushing economic concepts too aggressively into law. Moreover, in Vande Zande, Posner made an explicit analogy to Torts that, in my view, ought to have troubled Calabresi. After referencing “the duty of ‘reasonable care,’ the cornerstone of the law of negligence,” Posner invoked “Judge Learned Hand's famous formula for negligence” (famous, in no small part, thanks to Posner!) from United States v. Carroll Towing, 159 F.2d 169, 173 (2d Cir. 1947). (Torts students might remember this as the “BPL formula.”)

But, of course, Hand’s variant of cost-benefit analysis is just one way of giving content to “reasonableness”; we might just as easily consult common sense understandings of what seems appropriate, given the stakes. This is a very Calabresian point. But rather than question whether cost-benefit analysis ought to dominate this particular "reasonableness" inquiry (or interrogating the narrow set of benefits and costs that Vande Zande identified), Borkowski appeared to confirm that the Vande Zande approach was correct. (For a different view, see the EEOC’s 2002 guidance on the ADA: “Some courts have said that in determining whether an accommodation is "reasonable," one must look at the costs of the accommodation in relation to its benefits. . . . This "cost/benefit" analysis has no foundation in the statute, regulations, or legislative history of the ADA.”)

As a pair, Borkowski and Vande Zande sent a powerful message. They have been credited with "establish[ing] cost-benefit analysis as the cornerstone of reasonable accommodation jurisprudence.” Christopher B. Brown, Note, Incorporating Third-Party Benefits into the Cost-Benefit Calculus of Reasonable Accommodation, 18 Va. J. Soc. Pol'y & L. 319 (2011) (arguing that if cost-benefit analysis is the reigning paradigm, we ought to draw on Elizabeth Emens’s insights about the third-party benefits

of disability accommodations). The prominent disability law scholar Michael Ashley Stein describes Borkowski and Vande Zande similarly in "The Law and Economics of Disability Accommodations," 53 Duke L.J. 79, 96 (2003) -- an article that, in retrospect, looks noteworthy for showing just how much economists had been able to set the frame.

So, how do we judge a case like Borkowski? Looking at the decision overall—not just the language on “reasonable accommodation”—it appears to provide more room for argument for disabled plaintiffs than they had been getting, and therefore less room for summary dismissals. In this sense, it prioritized the value of equality. At the same time, Borkowski contributed to the “market discourse” that continues to affect the way that disabled employees and potential employees think of themselves and their rights. As Katharina Heyer has astutely noted, in a review of David Engel and Frank Munger's Rights of Inclusion, the cost-benefit standard in disability employment litigation is part of a broader framework that “focuses on the employer’s bottom line” and encourages people to believe that to request an accommodation is to claim some kind of “special right” rather than to seek equal opportunity (Heyer, 270-71). (For further thoughts on why cost-benefit analysis has worrisome implications for disability inclusion, see my 2022 LPEblog post on this topic. In retrospect, part of what concerned me is the behavioral economics phenomenon of "anchoring," another very Calabresian point!)

|

| Credit |

How to conclude? Fortunately, historical interpretation is not a zero-sum endeavor; we do not have to make “tragic choices.” My final assessment is that Calabresi’s legacy vis-à-vis “the economic style” is not unlike how he has long described Torts in the U.S. That is, it is a “mixed system.” Tort law is “mixed,” Calabresi has explained, in that one could never honestly describe its thrust as primarily libertarian or primarily collectivist; it is somewhere in between (OI, v.1, 368). Relatedly, Tort law is “mixed” in the goals it pursues. A concern for efficient use of social resources is apparent in some doctrines, but so, too are desires to correct perceived injustices, compensate injured people, spread costs, and express judgments about what society will and will not tolerate (OI, v.2, 271). All of these impulses exist at the same time. The ultimate lesson to take from Outside In and from these reflections is that Calabresi's legacy is similarly multi-faceted. We might wish for a simpler account, but to insist on such a narrative would do damage to the truth, and maybe also to each other as human beings. That would be an outcome Calabresi could not abide.

-- Karen Tani

* In this post, as in previous ones, I include some quotes from Calabresi himself. These come from Silber's interviews. One note of caution is that, as Silber explains in a helpful Author's Note, the "fluid monologue" one finds in the book is not a verbatim transcript. The language attributed to Calabresi was no doubt his own (as I think people who know him would attest), but its presentation on the page was "craft[ed] out of [interview] transcripts." (OI, v.1, xiv)

** Here’s the regulatory language that Borkowski quotes: “Reasonable accommodation may include: (1) making facilities used by employees readily accessible to and usable by handicapped persons, and (2) job restructuring, part-time or modified work schedules, acquisition or modification of equipment or devices, the provision of readers or interpreters, and other similar actions.” If you're interested in the history of Section 504 and the law's openness in its early years, I recommend Richard Scotch's From Good Will to Civil Rights. See also my forthcoming piece in Disability Studies Quarterly.