“A flock of pelicans, their white wings dyed

apricot by the setting sun, sailed low over the acacia trees of the garden with

a sound like tearing silk, and the sudden swish of their passing sent Alice’s

heart into her throat and dried her mouth with panic”

The opening lines of M.M. Kaye’s

Death in Kenya, transports the reader into Flamingo

a sprawling plantation on the banks of Lake Naivasha dominated by the huge

sprawling single storied house with “thatched roofs, wide verandahs and

spacious rooms paneled in undressed cedar wood, that defied all architectural

rules and yet blended with the wild beauty of the Rift Valley” dominated by the

septugenaraian Kenyan settler, Lady Emily De Brett, tramping about the estate

in her scarlet dungarees, flashing diamonds and a pith helmet. Despite the

gardens bursting with color, frolicking hippos, tea on the verandah, the army

of servants, the heady round of picnics to the Crater Lake and sundowners with

friends, there’s at atmosphere of lurking menace. The year is 1955, and despite

the official narrative being that the Mau Mau rebellion had been crushed,

characters worry about the Mau Mau on the run or being disguised among the plantation

staff, particularly rumors around the mysterious “General Africa” (a reference

to Waruhiru Itote, the real life Mau Mau fighter who went by the name General

China) who was rumored to be in hiding near Naivasha. Flamingo itself had successfully held off a Mau Mau attack in the

past, though it’s manager had died in the crossfire. As the settlers drink they

umpteenth gin and tonic, they look over their shoulders convinced that the “secret

ceremonies, extortion, intimidation-same old filthy familiar ingredients

simmering away again ready to boil over in the drop of the hat”. The lurking

tension spills into outright fear, as one by one characters are murdered, and

while it could well be the Mau-Mau (the choice of weapons includes a panga and

an poison tipped Masai arrow), it’s equally likely to be one of the small

community of Europeans living around the plantation.

I

read Death in Kenya in the Fall of 2016, after a day’s research at the National

Archives of Kenya in Nairobi where the files I was reading portrayed another

kind of terror, unleashed upon the Kenyan population by the colonial state. As

documented extensively by scholars like Caroline Elkins and David Anderson and

leading up to a High Court case for reparations, the Kenyan Emergency saw the

suspension of civil liberties, tens of thousands of deaths, the imprisonment of

around 400,000 Kikuyu into concentration camps and “enclosed villages, torture,

beating, mutilation, castration and sexual assault. Ostensibly to curb the Mau

Mau insurgency, a guerilla movement prompted by the expropriation of land by

White settlers, the retaliation attacked not just the Mau Mau gureilla fighters but a large

majority of the civilian population. By 1957, in a secret memoranda, the

Attorney General advised the Governor that the situation was prompting “comparisons

with Nazi Germany” and argued for a legal regulation of torture, famously

saying “those who administerviolence … should remain collected, balanced and dispassionate".

How

does one read light fiction set amid such unspeakable violence? At first,

Kaye’s sympathies with the settlers seem clear, as she says in the Authors

note, much of opinions voiced by her characters were taken from life, and very

few of the Kenya born settlers would believe the “winds of change” would blow

strongly enough to blow them out of the country they looked upon as their own.

This comes through brutally when Drew Stratton, the swarthy sunburned settler,

who walked like a cowboy displays a tally of “Mau Mau” kills on the verandah to

the queasy Victoria Caryll, newly arrived from England. Stratton and his

friends are reported to have gone underground, with blackface, to infiltrate

the Mau Mau groups. Describing the horrors of the Mau Mau, and the losses

suffered by loyalist Africans and Europeans, Stratton roughly rejects

Victoria’s plaintive statement that “it is their country” making the case for

settler colonialism in the crudest possible terms, “I want to stay here, and if

that is immoral and indefensible colonialism, then every American whose pioneer

forebears went in the covered wagon to open up the West is tarred with the same

brush; and when the UNO orders them out, we may consider moving”.

It is here, in its crudest and most

violent articulation, that the uncertainties of the settler imagination are

also highlighted. The awareness that their methods are under critique, the role

of the UN and the shift in power towards the United States. The self-awareness

comes through in Stratton’s apology for “the grossly oversimplified lecture on

the Settler’s point of view”. Settler

society is seen as a corrupted European society, as the gentle Alice de Brett

shudders at the “casual attitude of most women towards firearms and the sight

and smell of blood”. Morals are seen as lax, and several married characters are

having affairs outside their marriages. Kenneth Brandon, the Byronic 19 year

old, “capacity for falling in love with other men’s wives” makes him qualified

as the right type for Kenya.

Kenyan settlers, particularly the

hedonistic aristocrats who belonged to the Happy Valley Set had making

international scandal pages including its very own real life murder mystery,

when the Earl of Errol was foundmysteriously shot in his Buick in Ngong road. His lover’s husband another

British aristocrat was tried and acquitted of his murder and would later commit

suicide. As Lady De Brett asserts, it would unlikely that any jury in Kenya

would find her (and by implication any prominent settler) guilty of murder.

Martin Weiner and Elizabeth Kolsky have documented that Europeans were rarely

found guilty of violence in colonial trials. The impunity of white violence and

close, besieged nature of settler society, also makes it awkward for the police

inspector to conduct his investigation having to interrogate and detain his

friends and social acquaintance.

While

Kaye had spent a short period of time in Kenya, her powers of observation on

local culture are acute and are reflected in the book. A key alibi is

established by several African staff members hearing a suspect play a piano,

and when the suspect suggests that “none of the servants would know the

difference between one tune and another”, the inspector points out that the

average African has a better ear for music than one imagines. Peter Leman’srecent work traces how orality in accounts of legal trials has the “the capacity to challenge the narrative foundations of

colonial law and its postcolonial residues and offer alternative models of

temporality and modernity that give rise, in turn, to alternative forms of

legality”. Songs, verbal oath takings and music formed a key part of the

evidence in the famous Kapenguria trial, which sought to prosecute Jomo

Kenyatta and other Kikuyu leaders for managing the Mau Mau.

The violence against Africans during the Emergency is an

uncomfortable reminder offstage, as a character worries about her maid giving

evidence to the police, “they may take here away and hold her for questioning.

You know what they are like”. Another notes that the police had roped into the

house servants for questioning and turned the labour lines on the plantation

“into the nearest thing to a concentration camp”. The role of the Brandons, Flamingo’s neighbours, in the brutal suppression of the revolt,

offers a possibility that the Mau-Mau might take revenge by putting poison in

their medicine box. As Lady Brett acknowledges, there are things worse than

murder, including, “trials, hanging, suspicion, miscarriage of justice”.

As Erik Lindstrum shows

in his recent article, British knowledge about violence in the colonies was

both widespread, but also “fragmented and ambiguous”. British newspapers trying

to position themselves as neutral failed to convey the extent of colonial

violence and some of the most widely circulated narratives were framed by

fiction and film. The

solution to Death in Kenya (not to give away spoilers) is an ambiguous

statement to the question of the settler colony. The serial murders insanity is

driven by their desire to mark out a permanent presence in the colony, to

master its future, even though it requires the sacrifice of English men and

women. The murder is also revenged by an African, posing a problem for the

British policeman, who don’t know what to do with an African who had killed a

European but in the process saved the life of another.

Murder by the Panga: The Bassan

Murder Case

In

1960, the plot of Death in Kenya seemed to take real life turn. Satyavadi

Bassan, a young Kenyan-Indian and her two infant daughters were found hacked to

death by a panga in their car on the road to Nyeri. Pyarelal Bassan, her

husband and her four year old daughter were also found gravely injury and

recounted at attack by three African men who had stopped their car, demanded

money and attacked the family. The Indian Association of Nyeri rejected the

idea of a robbery gone awry and insisted the murder was political, linking it

to secret gatherings of Africans and the targeting of Indians as “outsiders”

and “parasites” in Kenyan nationalist rhetoric. The use of the panga (like the

wounds of Alice de Brett in Death in Kenya) were seen as “reminiscent of the

Mau Mau killings”. As Sana Aiyyar in her

study of the Indian diaspora in Kenya notes, “the use of the panga and

mutiliation..became the catalyst for politicization of the Nyeri murder”. Aiyar

argues that wile the Indian leaders in Kenya attacked African leadership for

not condemning the violence, the emergent African political leaders also

assumed that the attack was carried out by Africans and marked a “resurgence of

ritualistic violence that threatened their leadership”

The subsequent trial and

investigation revealed, as in Kaye’s who-dunnit, the crime originated neither

from economic reasons nor the political churn of nationalism, but from a domestic setting. Pyarelal Bassan

was found to have hired the men to murder his wife and children, and the trial

hinted at both Pyarelal and Satyavati having extra-martial liaisons. Once again we see a crime that originates in the "malice domestic" of a settler society, being initially framed as a crime arising out of the violent churn of African politics.

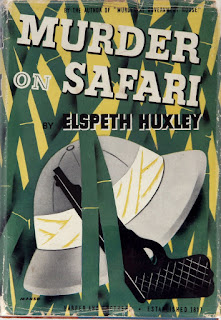

Crime in the Colony: Elspeth

Huxley’s Murders in Chania

Colonial

Kenya also forms the setting for a series of murder mysteries by ElspethHuxley. Huxley, the author of over 42 books is best known for her memoir, TheFlame Trees of Thika, serialized in television and frequently analysed by

literary scholars working on colonialism, memory and nostalgia. Huxley’s murder

mysteries set in the fictional country of Chania (standing in for Kenya) draw

richly from colonial legal sources.

Katherine Luongo opens her

compelling study of Witchcraft and Colonial Rule in Kenya, 1900-1950 with an

extract from Huxley’s first crime novel, Murder

at Government House (1937), a long digression from the process of

investigating the murder of the Governor of Chania in his study.

“included

a lengthy, elaborate anecdote about another high-profle murder case in the

colony, the “Wabenda witchcraft case.” Chania’s secretary for Native Affairs

recounted the local narrative of the “Wabenda witchcraft case” to the detective

in charge of investigating the governor’s murder: The Wabenda, among whom

witchcraft was more strongly entrenched than among most Chania tribes, had put

to death an old woman, who, they alleged, was a witch. The woman had stood

trial before the elders and the chiefs of the tribe, had been subjected to a

poison ordeal, and found guilty of causing the death of one of the head chief’s

wives and the deformity of two of his children. Then, following the custom of

the tribe, she had been executed, in a slow and painful manner. . . . It was a

horrible death, but meted out after due trial, and for the most anti-social crime

in the Wabenda calendar. After outlining

the circumstances surrounding the witch-killing, the secretary for Native

Affairs turned to how Wabenda and British conceptions and processes of justice

collided in the context of the case. He elaborated, The chiefs and elders were

put on trial for the murder of the old witch. Forty-i ve of them appeared in

the dock – a special dock built for the occasion. They did not deny that the

witch had died under their instructions. They claimed that in ordering her

death they were protecting the tribe from sorcery, in accordance with their

obligations and traditions. They were found guilty and condemned to death.

There was no alternative under British law; the judges who pronounced sentence

did so with reluctance and disquiet.

But

as the secretary for Native Affairs noted, the “Wabenda witchcraft case” was

not easily resolved by the sentencing of the forty-i ve Wabenda in the British

courts. He noted, The Government was in an awkward position. It could not,

obviously, execute forty-five respectable old men, many of them appointed to

authority and trusted by the Government, who had acted in good faith and

according to the customs of their fathers. In the end it had compromised.

Thirty-four of the elders had been reprieved and pardoned. Ten had been

reprieved and sentenced to terms of imprisonment. In one case, that of the

senior chief who had supervised the execution, the death sentence had been

allowed to stand. 4 Finally, the secretary for Native Affairs addressed some of

the ways in which the case was figured in additional “judicial settings”; in the

Supreme Court of Chania, in the governor’s Privy Council, and in the equally

salient “courts of opinion” of various metropolitan and Chanian publics. He

explained, The case was not yet over. The sentenced chief, M’bola, had appealed

to the Supreme Court, lost, and finally appealed to the Privy Council. Feeling

in native areas ran high. Agitators had seized upon the case as an example of

the tyranny and brutality of British rule. Administrators feared serious troubles

should it be carried out.”

As

Luongo asks, “Why would a story of

witchcraft, law, and the colonies have resonated with British reading publics

at home and abroad?”. She does on to show that these fictional events mirrored a real life witch killing case in the 1930s,

i.e. the Wakamba Witch trials, which “long-standing, circuitous, imperial story

of African witchcraft beliefs and practices challenging the ability of colonial

states to achieve law and order in the British African Empire”. Huxley’s who-dunnits are not Mayhem Parva imported to the colony, but arise from it’s settings. For instance, in Death of a Safari, a lions kills and a charging buffalo are turned into weapons of murder. or in African Poisons shows extensive knowledge of land use rights, animal husbandry and African toxins.

Huxley,

unlike Kaye, was a long term resident in Kenya and her murder mysteries offer better

rounded characters and complex accounts of the changing political situation.

The women are not damsels in distress, but professionals.

In Murder in Government House, the

detective is assisted by Olivia Brandeis is an anthropologist who documents a

Kenyan secret society with rituals of seizing power from the English (possibly

inspired by Mary Leakey), the safari in Murder

on an African Safari (1938) is led by the dashing aviatrix (modelled on real life

Beryl Markham) who flies ahead to spot the wild game; The African Poison Murders (1939) has a female solicitor trying to set up

a practice (modelled on K.P Hurst, the sole female Barrister in Kenya who was

one of the rare European lawyers who had engaged to defend Africans accused as

Mau-Mau) and Thomasina Labouchiere is an assistant to the British commission

negotiating independence an at the Incident

at the Merry Hippo (1963) (mirroring perhaps Huxley’s own experience as an independent

member of the commission for the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland) . Her who-dunnits spaced out over two decades

offer an acutely changing awareness of politics, for instance in African Poison Murders tensions break

out between English and German settlers, when a possible Nazi sympathizing German

is found poisoned on his farm. She demonstrates acute insights into the nature

of the colonial bureaucracy, outlining the differences between different kinds

of training in Murder in Government

House, or the awareness that the Governor can suspend the right of a

solicitor to practice in African Poison

Murders.

The Historian as a Detective: Richard Rathbone's Murder and Politics in Colonial Ghana

How can legal historians draw from structures of detective novels? In many ways, their methods of collecting and evaluating evidence, building off fragments and constructing the "who dunnit" is the same. One model is Richard

Rathbone's Murder and Politics in Colonial Ghana, which as reviewer notes, “is not the West African companion to Elspeth Huxley's East

African whodunnit, Murder at Government House. Nor, despite its trailer of

'Colonial Ghana' (itself a curious chronological byline), is it a critique of

Colonial Office administration” Rathbone uses the “ritual murder” of an Ghanian chief during a

royal funeral procession, and subsequent investigation and trial to trace how

traditional and new Ghanian elites engaged with the local and imperial

administration during the transition from late colonial rule to independence. The

book is also a whodunit, as Rathbone seeks to also solve the mystery of Akea

Mensa’s death (aided by none other than mystery writer and British civil

servant P.D James, who is acknowledged in the book). Did Mensa really die or did

he go into exile? Was this suicide, an accidental fall into a mineshaft or a

public lynching? Was the motive “ritual murder” or unpopular treasury reforms?

In my next post, I'll return to M.M Kaye's sojourns to Zanzibar, Cyprus, India and Germany and reflect upon the absence/presence of empire in the Golden Age Detective Novel

PS: I am grateful to Surabhi Ranganathan for talking through some of these ideas.

PS: I am grateful to Surabhi Ranganathan for talking through some of these ideas.