[The exam in my American legal history course consists of two essays, one on the legal history of some regulatory regime my students did not study but which developed much like those they did. The other is a biographical essay on some Black, Jewish, and/or female lawyer who made for an interesting comparison with those we studied. Below is a slightly augmented version of the first essay from this year's exam. For earlier ones, start here. DRE.]

Although the world’s first powered flight took place in the United States on December 17, 1903, when Orville Wright flew 120 feet on a North Carolina barrier island, for many years the U.S. lagged behind other nations in promoting and regulating aviation. As an American treatise writer observed, while Americans still regarded aviation as “a very dangerous sport carried on by the more adventurous barnstormers of the day,” Europeans had taken it seriously as “a war weapon and a means of fast transportation knowing no national boundaries.” Their governments directly regulated air transportation and placed civilian and military aviation under a single, national Ministry of Aviation. In contrast, the United States did not even begin scheduled air mail service until 1918. Two more years passed before transcontinental air service arrived, with night flights guided by bonfires.Indeed, well into the 1920s, American jurists still had not cleared the most fundamental legal hurdle to commercial flight, the maxim Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos (“Whoever owns the soil, owns to the heavens and to the depths”). If followed strictly, a commentator observed, the ad coelum maxim would “create a private property right in the airspace, placing absolute ownership to the heavens in the surface owner.” Aviators would not be able to negotiate with the countless surface owners whose airspace they crossed and would therefore face “continual litigation in trespass.” Conferring eminent domain power on airlines also was no solution, if only because weather commonly forced aviators to depart from their flight plans.

American lawyers set out to solve this law-made problem. Soon after World War I, a committee of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws started work on a model statute. Approved by the American Bar Association in 1922, it legalized flight over the land of others unless it occurred “at such low altitudes as to interfere with the then existing use to which the land . . . or the space above the land . . . is put by the owner.” In 1923, a Minnesota trial judge reached the same result without a statute. The ad coelum maxim, wrote Judge J. C. Michael, was “adopted in an age of primitive industrial development . . . when any practical use of the upper air was not considered or thought possible.” But now, thanks to “marvelous . . . mechanical inventions,” the “great public usefulness” of air travel was obvious to all. “Modern progress and great public interest should not be blocked by unnecessary legal refinements,” he declared. Courts had long adapted common-law rules to “new conditions arising out of modern progress”; now they should recognize that “the upper air is a natural heritage common to all of the people.”

A single federal agency charged with regulating all aspects of civilian aviation did not arrive until 1938. Until then, two different federal departments-and, briefly, an existing independent commission-imperfectly set aviation policy.

|

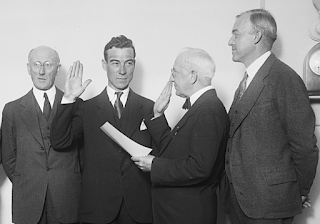

| MacCracken, right, observes his successor's swearing-in (LC) |

Starting in 1922, Secretary Herbert Hoover lobbied for the creation of a bureau within the Department of Commerce to regulate civilian aviation. Congress finally obliged with the Air Commerce Act of 1926, which empowered the Secretary of Commerce to a register and inspect aircraft, examine and rate pilots, certify airports, and promulgate safety regulations. It also created an “Aeronautics Branch” within the Commerce Department, headed by an Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics, nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The first holder of that office was William MacCracken, a 1911 graduate of the University of Chicago Law School, who had served as a flight trainer during World War I, had chaired the American Bar Association’s Committee on the Law of Aeronautics since its creation in 1920, and helped draft the Air Commerce Act after studying European air ministries. “The great deal of discretion” the statute vested in the Commerce Department, MacCracken said, was necessary if its regulations were to “keep pace with the development of this new art.” Although some aviation lawyers, hoping to end competition from small “fly by night” air carriers, argued that the Air Commerce Act gave Hoover the power to establish price-and-entry regulation for the industry by issuing a limited number of “certificates of convenience and necessity” to air carriers for particular routes and setting the prices they could charge passengers, MacCracken could never persuade Hoover to take that step, probably because Hoover wanted the industry to organize itself through its own associations.

That left the job of imposing order on the market for air travel to the Post Office Department. Starting with the Air Mail Act of 1925, the United States heavily subsidized the airline industry with intentionally generous air mail contracts. In 1929, for example, the federal government paid airline over $9 million more to carry air mail than it received in postage on it. With passenger service rudimentary into the 1930s, those subsidies were needed to keep commercial aviation aloft.

With the first round of four-year contracts, awarded to legions of short-distance carriers, expiring in

1929, now-President Herbert Hoover’s new Postmaster General Walter Brown, a dominant figure in the Republican Party of Ohio, decided to award air mail contracts to a handful of financially secure carriers capable of flying an entire transcontinental route rather than rely on a patched-together network of financially precarious companies. (“A bankrupt is a poor person to do business with,” he explained.) William MacCracken, who had resigned as Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics to open an aviation-focused practice in Washington, DC, was one of several lawyers for the air carriers most likely to win transcontinental contracts, backed Brown and drafted the McNary-Watres Act, passed, in April 1930, to enable Brown to implement his plan.

Another lawyer was a woman. Since 1921, Mabel Walker Willebrandt (1889-1963) had been an Assistant Attorney General in the U.S. Department of Justice, tasked with overseeing federal prisons and enforcing Prohibition, since 1921. She had campaigned for Herbert Hoover in 1928 and expected a better job in his administration. When none arrived, she accepted the offer of a retainer by a recently created holding company, Aviation Corporation (AVCO), assembled from scores of small carriers by two great New York investment banks. AVCO wanted someone to help get their interests written into what became the McNary-Watres Act and to ensure that the Postmaster General designate its air fields as regular stops for air mail planes. A Washington lawyer told AVCO that not only could Willebrandt handle the legal phases of the operation; she also had “the necessary contacts,” including her good friend Postmaster General Brown! Willebrandt got the job and, some years later, would go on to chair the ABA Committee on Aeronautical Law.

Invoking his broad new powers to award ten-year contracts, Brown convened airline lawyers and executives in what his critics later called “the Spoils Conference.” After outlining the system he wanted, Brown left the representatives of the air carriers to bargain amongst themselves. Unsurprisingly, the lawyers failed to agree–much shouting ensued–and Brown ended up imposing a plan suggested by McCracken, under which four carriers, including his client (later known as TWA) and AVCO (later known as American Airlines), got transcontinental contracts. Payments to air mail carriers reached $19.5 million in 1933.

MacCracken

spoke out in September 1933 when economy measures by Franklin D.

Roosevelt’s new Secretary of Commerce left the nation’s air navigation

system in a dangerous condition. The lives and property of those who

fly had become “a plaything of politics,” he charged. But MacCracken’s

own time in the barrel was fast approaching. In the fall of 1933, Hugo

Black, then U.S. Senator from Alabama, opened an investigation of the

Spoils Conference. “It was at this stage that the money changers saw

their golden opportunity,” Black declared. “The control of aviation had

been ruthlessly taken away from men who could fly and bestowed upon

bankers, brokers, promoters and politicians, sitting in their inner

offices, allotting themselves the taxpayers’ monies.” Black’s committee

subpoenaed MacCracken and his office files, from which a client then

removed documents. McCracken refused to testify, claiming

attorney-client privilege, was held in contempt of Congress, and, after

battling the conviction up to the U.S. Supreme Court, served his brief

sentence in the Willard Hotel, ostensibly because the Senate’s

Sergeant-at-Arms had nowhere else to confine him.

By early 1934, a

historian has written, “allegations of conspiracy, corruption, and

favoritism [appeared] in massive headlines in newspapers across the

country.” FDR’s Postmaster General James Farley canceled all air mail

contracts as the product of corrupt bargaining and gave the Army Air

Corps the job of transporting air mail. The results were disastrous: in

less than a month, sixty-six forced landings left twelve army pilots

dead.

Congress acted at once. The Black-McKellar Act, passed in

June 1934, divided national aviation policy still further. Under a new

name (the Bureau of Air Commerce), the Aeronautics Branch carried on

its old duties at the Department of Commerce. The Post Office

Department continued selecting the carriers of air mail, awarding them, a

critic charged, solely on the requirements of air mail service,

heedless of the need to rationalize passenger service. But the Act gave

the job of setting rates for carrying air mail to the Interstate

Commerce Commission, with its long history of apolitical rate-setting

for railroads. (Rates for carrying passengers continued to be

unregulated by any government body.) Aviation industry figures

complained that the ICC was too protective of railroads to do the job

right.

FDR appointed a committee to study alternatives, but

Postmaster General Farley and Commerce Secretary Dan Roper fought all

attempts to transfer their jurisdiction elsewhere until 1938, when

Congress finally passed the Civil Aeronautics Act (CAA). It created, in

addition to the precursors of today’s National Transportation Safety

Board and Federal Aviation Administration, a body soon renamed the Civil

Aeronautics Board (CAB). It finally gave the biggest air carriers what

they had long sought: a regulatory body that would protect their routes

and revenues from what they considered “ruinous competition,” by

issuing certificates of public necessity and convenience for particular

routes and fixing the prices carriers could charge for carrying

passengers and mail. Under the CAA’s “grandfather clause,” eighteen

airlines automatically received permanent certificates for their

existing routes. To get new routes, they or new air carriers had to

show that they were “fit, willing, and able” to operate flights reliably

and that “the public convenience and necessity” required that the

routes be flown. All fares had to be “just and reasonable,” determined

with reference to five specified and open-ended factors and such other,

unspecified factors as the CAB thought appropriate. The CAA also

provided that the “findings of facts by the [CAB], if supported by

substantial evidence, shall be conclusive” in any judicial challenge to

its orders.

In October 1938, Edgar Gorrell, a spokesman for the

grandfathered airlines, acknowledged that “the tendency to make the same

agency both prosecutor and judge quite properly evokes protest,” but he

argued that to “transfer to the courts the judicial functions now

vested in administrative bodies” would be disastrous. Yes, a court

could overturn the order of the CAB “only if there is no possible

justification for the administrative action,” even if the court would

have decided otherwise had it been its decision to make. But Gorrell

was unconcerned. He expected the CAB to “exercise self-restraint in

passing upon the propriety of the conduct of management.” Of course, if

the CAB ever attempted to “do the work of industry,” the air carriers

would ask the courts to defend their prerogatives.

Our best view

of the CAB’s procedures is a monograph prepared by a recent law graduate

on the Walter Gellhorn-directed research staff of the Attorney

General’s Committee on Administrative Procedure (AGCAP). Its author

observed that the CAB attempted “to determine broad economic questions

through a procedure closely resembling the course of a lawsuit between

individual.” In fact, the resemblance was imperfect. When the CAB set

a hearing on, say, whether to issue a certificate of convenience and

necessity, it notified not only the applicant but also all the nation’s

air carriers and to transport associations, as well as any affected

state or municipality. Any interested party could become an

“intervenor” and oppose the certificate and present evidence. The CAB

told its trial examiners to exclude only “plainly inadmissible”

evidence. Because the relevant standards were so broad, they rarely

excluded any. The applicant’s lawyer could cross examine any witness,

including the intervenors’, who testified under oath.

Once all

the testimony was in, the applicants and intervenors could make oral

arguments to the trial examiner and submit briefs before the trial

examiner wrote his “intermediate report.” When finished, the trial

examiner’s report was released to the public; any party might except to

its findings of fact and conclusions of law. Then these exceptions,

with the record and the trial examiner’s intermediate report, went, not

to the five-member CAB but to a “Consulting Committee,” consisting of a

lawyer in the CAB’s general counsel office with no previous connection

to the case, a trial examiner (who might or might not have presided at

the hearing); and a member of the CAB’s staff of accountants and

economist. Applicants and intervenors could not discuss the case with

the Consulting Committee, but the Consulting Committee could and did

consult the CAB lawyer who appeared at the hearing or the trial examiner

who presided, if he was not one of its members. The Consulting

Committee prepared a draft opinion, which might bear little resemblance

to the intermediate report, and order that it sent to the five-member

CAB. At its meeting, the CAB general counsel and the member of the

Consulting Committee who drafted the opinion were present, but not the

parties or intervenors. At last, the CAB granted or denied the

certificate and issued its opinion.

The author of the AGCAP

monograph claimed that CAB opinions addressed “the questions of law and

fact in much the same way as do the decisions of an appellate court.”

Others denied the resemblance. After resigning in protest, the former

CAB member Louis Hector complained that the agency’s decisions followed

no consistent principle. The CAB altered its policies “from case to

case,” he said, “with no advance notice, no opportunity for argument by

the parties on a proposed change in policy, and no opportunity for the

parties to present new evidence in the light of the new policies.” The Covington & Burling lawyer Howard Westwood agreed: CAB opinions were

“grubby, uninspired, and sometimes incoherent.”

Yet Gorrell’s

1938 predictions proved correct: as a rule, the CAB respected the

managerial prerogatives of the grandfather airlines and protected their

markets, and as a rule the courts let the CAB alone. The best chance to

interject some competition into the airline industry came in 1946, when

Harry Truman appointed James Landis chair of the CAB. Landis had been

Felix Frankfurter’s prized student and chaired the Securities and

Exchange Commission before becoming dean of the Harvard Law School in

1937. His tenure at CAB was a deep disappoint to him. On all important

matters he was outvoted by his fellow members: a former Republican

congressman, a former Democratic senator, MacCracken’s successor as

Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics (who later became an

airline executive), and a former Assistant Postmaster General in charge

of air mail.

Perhaps the most galling moment for Landis

involved Truman himself. The CAA provided that the CAB’s issuance of

certificates of convenience and necessity for international flights or

flights between the United States and its possessions “shall be subject

to the approval of the President.” In 1946, the CAB certified a

Northwest Airlines route from Seattle to Honolulu, but because Hawaii

was still a territory, the matter went to the White House to be

finalized. Strange things then ensued. First, Truman denied Northwest a

certificate because, he somehow concluded, the route would not be

profitable. Not long thereafter, however, the president reversed

himself and approved Northwest’s certificate. This brought a protest

from Pan American and, a few weeks later, Truman’s decision to certify

both Northwest and Pan Am. Thus, a historian wrote, “the White House

ordered certificates for both airlines on a route it originally rejected

as too thin to sustain even one line.” What Landis probably thought at

the time, he said out loud sometime after Truman declined to reappoint

him in December 1947: Under Truman, victory in overseas airline

decisions went to whomever “supplied the palace guard at the White House

with adequate quantities of Bourbon.”

Could one challenge such

presidential decisions in court? You might have thought so from the

CAA, which made “any order” of the CAB subject to external review. The

only express exception was for orders involving foreign air carriers,

which the CAA said courts could not review after the President had

approved or rejected them. Although the section did not expressly

except the international or territorial flights of American carriers,

when such a case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Robert H.

Jackson, writing for a 5-4 majority in 1948, ruled that the President’s

decision was not reviewable. In exercising his powers as

“Commander-in-Chief and as the Nation’s organ in foreign affairs,”

Jackson wrote in Chicago & Southern Air Lines v. Waterman Steamship Corp.,

the President had access to “intelligence services whose reports are

not and ought not to be published to the world. It would be intolerable

that courts, without the relevant information, should review and

perhaps nullify actions of the Executive taken on information properly

held secret.”