--Dan Ernst

Monday, January 31, 2022

Tushnet's "Hughes Court"

Witt on the US and Postwar International Law

John Fabian Witt, Yale Law School, has posted The View from the U.S. Leviathan: Histories of International Law in the Hegemon:

Histories of international law more or less follow the epistemic position of the jurisdiction in which they arise. The parochial Anglophone student of the comparative literature in the history of international law instantly sees a version of this phenomenon in action. With notable exceptions, even sophisticated work in the history of international law in the U.S. is importantly different from English-language work in the same field that has begun to pour out from scholars based in the U.K., Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and elsewhere. In this chapter, I propose that this is because U.S. scholars since at least the Second World War have taken up the history of international law through a set of questions and presuppositions structured by a standpoint inside the leviathan. The most powerful player on the international stage – the United States – has exerted a gravitational pull on scholars writing the history of international law and on the functions that such histories serve. In recent years, however, the cross-border professionalization of the field is helping produce histories increasingly further afield from, or at least in a newly complex relationship to, the epistemic domination of the hegemon.--Dan Ernst

Saturday, January 29, 2022

Weekend Roundup

- The Society for the Study of Nineteenth-Century Ireland has a CFP for its in-person annual conference 2022, New Perspectives on Conflict and Ireland in the Nineteenth Century, to be held at University College, June 24-25, 2022.

- The constitutional historian Jack Rakove is interviewed about his life and work at length here.

- The top five articles in Labor: Studies in Working Class History are ungated through Monday.

- James M. Banner, Jr. will speak online on “The Election of 1801: Constitutional Event,” as the guest of the David Center for the American Revolution.

- Reminder: On Monday, January 31, at 12:00, Christopher Brooks, East Stroudsburg University, speaks via Zoom on John Stewart Rock: A Trailblazed Path to the Supreme Court Bar under the auspices of the Supreme Court Historical Society.

- The German Law Journal has posted ungated recently conducted oral histories of Aharon Barak (born in 1936), President of the Israel Supreme Court (1995-2006); Sabino Cassese (born in 1935), Justice of the Italian Constitutional Court (2005-2014); and Dieter Grimm (born in 1937), Justice of the German Federal Constitutional Court (1987 to 1999).

- ICYMI: Our Legal Heritage: When Holyrood offered sanctuary to debtors (Scottish Legal Times). Eight Key Laws That Advanced Civil Rights (History Channel). Disqualify judges because they write legal history? Judge A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. would like a word (Law.com).

Weekend Roundup is a weekly feature compiled by all the Legal History bloggers.

Friday, January 28, 2022

Zier on In re Strittmater’s Estate

Magdalene Zier, a J.D. candidate at the Stanford Law School and a doctoral candidate in Stanford’s Department of History, has published “Champion Man-Hater of All Time”: Feminism, Insanity, and Property Rights in 1940s America, Michigan Journal of Gender & Law 28 (2021): 75-118:

Legions of law students in property or trusts and estates courses have studied the will dispute, In re Strittmater’s Estate. The cases, casebooks, and treatises that cite Strittmater present the 1947 decision from New Jersey s highest court as a model of the “insane delusion” doctrine. Readers learn that snubbed relatives successfully invalidated Louisa Strittmater’s will, which left her estate to the Equal Rights Amendment campaign, by convincing the court that her radical views on gender equality amounted to insanity and, thus, testamentary incapacity. By failing to provide any commentary or context on this overt sexism, these sources affirm the court’s portrait of Louisa Strittmater as an eccentric landlady and fanatical feminist.

This is troubling. Strittmater should be a well-known case, but not for the proposition that feminism is an insane delusion. Despite the decision’s popularity on law school syllabi, no scholar has interrogated the case’s broader historical background. Through original archival research, this Article centers Strittmater as a case study in how social views on gender, psychology, and the law shaped one another in the immediate aftermath of World War , hampering women’s property rights and efforts to achieve constitutional equality. More than just a problematic precedent, the case exposes a world in which the “Champion Man-Hater of All Time”--newspapers’ epithet for Strittmater--was not only a humorous headline but also a credible threat to the postwar order that courts were helping to erect. The Article thus challenges the textbook understanding of “insane delusion” and shows that postwar culture was conducive to a strengthening of the longstanding suspicion that feminist critiques of gender inequality were, simply put, crazy.

--Dan Ernst

"The Making of Consumer Law and Policy in Europe"

Just out from Bloomsbury: the anthology The Making of Consumer Law and Policy in Europe, edited by Hans-W Micklitz.

This book analyses the founding years of consumer law and consumer policy in Europe. It combines two dimensions: the making of national consumer law and the making of European consumer law, and how both are intertwined.

The chapters on Germany, Italy, the Nordic countries and the United Kingdom serve to explain the economic and the political background which led to different legal and policy approaches in the then old Member States from the 1960s onwards. The chapter on Poland adds a different layer, the one of a former socialist country with its own consumer law and how joining the EU affected consumer law at the national level. The making of European consumer law started in the 1970s rather cautiously, but gradually the European Commission took an ever stronger position in promoting not only European consumer law but also in supporting the building of the European Consumer Organisation (BEUC), the umbrella organisation of the national consumer bodies.

The book unites the early protagonists who were involved in the making of consumer law in Europe: Guido Alpa, Ludwig Krämer, Ewa Letowska, Hans-W Micklitz, Klaus Tonner, Iain Ramsay, and Thomas Wilhelmsson, supported by the younger generation Aneta Wiewiórowska Domagalska, Mateusz Grochowski, and Koen Docter, who reconstructs the history of BEUC. Niklas Olsen and Thomas Roethe analyse the construction of this policy field from a historical and sociological perspective.

This book offers a unique opportunity to understand a legal and political field, that of consumer law and policy, which plays a fundamental role in our contemporary societies.

--Dan Ernst

Thursday, January 27, 2022

Berger to Present in BC Legal History Roundtable

The organizers ask that attendees wear masks because of the small size of the Rare Book Room, and they regret that they will be unable to provide refreshments.

--Dan Ernst

Wednesday, January 26, 2022

AJLH 64:4

Articles

What Oath (If Any) Did Jacob Henry Take in 1809?: Deconstructing the Historical Myths

Seth Barrett Tillman

The American Bar Association Looks to England, 1924 and 1957

Christopher J Rowe

Victorian Railways Commissioners v Coultas: The Untold Story

Peter Handford

Book Reviews

Martha S. Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All

Kimberly A Hamlin

Bartosz Brozek, Julia Stanek, and Jerzy Stelmach (eds), Russian Legal Realism

Punsara Amarasinghe

--Dan Ernst

CFP: Early Modern Colonial Laws and Legal Literature

[We have the following Call for Papers. DRE.]

The Dynamics of Early Modern Colonial Laws and Legal Literature, 26-28 October 2022, Faculty of Law, University of Helsinki, Finland

The conference organizers invite papers exploring how legislative strategies of early modern colonial empires affected each other, what they had in common, and how colonial laws emanating both from Europe and the colonies themselves developed into different directions. Conference papers will look at early modern colonial legislation of the empires in multiple contexts: medieval inheritance of ius commune and legal pluralism; early modern transformations of legal orders, such as the growth of police regulation; and not the least, the local colonial realities and normativities.

Connected to the last point, contributions investigating local readings of "foreign" legal literature will also be welcome. One may ask what role legal literature had in the circulation of legal rules and concepts, and in confronting societal challenges. Examples from court practice and legislative bodies highlight these complex processes. "Legal literature" will not be understood in the sense of being strictly dogmatic or methodological, but in the broad sense of personally constructed texts on law, written for legal practitioners, both academically trained lawyers and laymen.

This conference will bring together legal scholars, historians, and social scientists to explore the complex entanglements of early modern colonial laws.

Confirmed keynote speakers are professors Thomas Duve (Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory, Frankfurt) and Andréa Slemian (University of São Paulo).

The conference is organized jointly by two projects, Comparing Early Modern Colonial Laws: England, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain (Academy of Finland, University of Helsinki) and Reading Law Glocally: Local Readings of Foreign Legal Literature in a Globalized World (Seventeenth to Early Twentieth Centuries) (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique / France, Ghent University, University of Helsinki, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid). The conference committee consists of professors Laura Beck (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), Serge Dauchy (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), Georges Martyn (Ghent University) and Heikki Pihlajamäki (University of Helsinki).

Please send, in one file, your abstract (max. 300 words) and short CV to the address:

heikki.pihlajamaki@helsinki.fi.

The language of the conference is English. There is no registration fee. The organizers will consider applications for reimbursement of travel costs and/or accommodation for junior researchers presenting papers. Participation online will be possible, and publication of the conference papers is foreseen. The deadline for submissions is March 31, 2022.

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

National Archives Digitizes DOJ and Supreme Court Records

CFP: A Conference on Coverture

[We have the following announcement. DRE.]

Married Women and the Law in Britain, North America, and the Common Law World, Gainesville, Florida, May 5-8, 2022

The University of Florida, Levin College of Law is hosting a conference on all aspects of coverture, broadly defined. This intimate conference will enable the participants to consider issues of marriage and married women's legal disabilities through multiple lenses, including by time period, legal system, as a colonial export, its economic and social impacts, as literary representations, and many others. If you are working on aspects of married women's legal incapacities in the common-law world, please consider submitting a paper. Accommodations for panelists during the conference will be covered. Publication opportunity may be available.

Please submit a 200 word abstract of your paper to Danaya Wright at wrightdc@law.ufl.edu by March 1, 2022 for consideration, or if you have any questions.

Monday, January 24, 2022

Stone on Constance Baker Motley's Housing Litigation

Donovan J. Stone, a 20211 graduate of the Duke Law School, has published Constance Baker Motley’s Forgotten Housing Legacy in the Utah Law Journal:

Constance Baker Motley led the legal assault on Jim Crow and became the first Black woman appointed to the federal bench. She spent two decades with the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund, assisting Thurgood Marshall in Brown v. Board of Education. Afterward, she desegregated the South’s public schools and universities and argued ten cases before the Supreme Court, winning nine. Motley also represented countless protestors jailed for their activism, including Martin Luther King, Jr.

Constance Baker Motley 1965 (LC)

Despite Motley’s achievements, scholars have largely overlooked her career. And those who have examined Motley’s work have generally focused on her efforts to dismantle school segregation. Public school desegregation was foundational to Motley’s LDF litigation, but her practice also extended beyond school desegregation. Motley filed scores of cases challenging racial discrimination in voting rights, public accommodations, and housing access.

Using archival research, this Article explores the latter category–Motley’s housing docket–through the lens of Stewart v. Clarke Terrace Unit No. 1, a case she litigated in Shreveport, Louisiana. Filed in 1954, Clarke Terrace was LDF’s first lawsuit challenging discrimination in privately constructed but federally insured housing developments. It sought to enforce the rights of African Americans who purchased homes in a new subdivision only to have nearby white residents sabotage the development. Uncovering Clarke Terrace challenges conventional narratives pigeonholing Motley as an education attorney. It highlights her housing advocacy and demonstrates that this work was pivotal to Motley’s clients, even if forgotten by historians. This analysis powerfully advances appreciation for and understanding of Motley’s civil rights legacy.

--Dan Ernst

ABF/Northwestern Legal History Colloquium

[We have the following announcement. DRE]

We are excited to announce that we will, once again, be hosting a collaborative ABF/Northwestern Legal History Colloquium this semester. As in the past, this colloquium will be a class for Northwestern law students (co-taught by Ajay Mehrotra and Nadav Shoked), as well as a workshop for the broader ABF legal history community.

The workshop will be held in-person, unless current pandemic conditions change, in Rubloff 339 at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law (375 E. Chicago Ave.) on Wednesday afternoons (4:10 – 5:10). The full schedule of speakers and password protected access to papers will be available soon on the ABF Legal History webpage.

We are looking forward to welcoming the following legal historians this semester:

January 26 – Allison Tirres (DePaul Law School)

February 2 – Joanna Grisinger (Northwestern U.)

February 16 – Kunal Parker (U. of Miami Law School)

February 23 – Stuart Banner (UCLA Law School)

March 9 – Barbara Welke (U. of Minnesota Law/History)

March 16 – Sophia Lee (UPenn Law)

April 6 – Amalia Kessler (Stanford)

April 13 – Emily Prifogle (U. of Michigan Law)

For more information, please contact Sophie H. Kofman, Academic Affairs Assistant, at the American Bar Foundation, at skofman@abfn.org.

Sunday, January 23, 2022

Cambridge History of Medieval Canon Law

The Cambridge History of Medieval Canon Law, edited by Anders Winroth, Universitetet i Oslo, and John C. Wei, has been published.

Canon law touched nearly every aspect of medieval society, including many issues we now think of as purely secular. It regulated marriages, oaths, usury, sorcery, heresy, university life, penance, just war, court procedure, and Christian relations with religious minorities. Canon law also regulated the clergy and the Church, one of the most important institutions in the Middle Ages. This Cambridge History offers a comprehensive survey of canon law, both chronologically and thematically. Written by an international team of scholars, it explores, in non-technical language, how it operated in the daily life of people and in the great political events of the time. The volume demonstrates that medieval canon law holds a unique position in the legal history of Europe. Indeed, the influence of medieval canon law, which was at the forefront of introducing and defining concepts such as “equity,” “rationality," "office,” and “positive law,” has been enormous, long-lasting, and remarkably diverse.

In addition to the editors, the other contributors are Caroline Humfress, Abigail Firey, Greta Austin, Christof Rolker, Wolfgang P. Mueller, Martin Bertram, Andreas Meyer, Péter Erdo, Norman Tanner, Gisela Drossbach, Gero Dolezalek, Anthony Perron, Susan L'Engle, Charles de Miramon, Elizabeth Makowski, M. Izbicki, Rob Meens, Thomas Wetzstein, Sara McDougall, Franck Roumy, Lotte Kéry, Edward Peters, Frederick Russell, Ryan Greenwood, Peter G. Clarke, Peter Landau, and Thomas Izbicki. The TOC is here.

--Dan Ernst

Saturday, January 22, 2022

Weekend Roundup

- Over at HNN, Bruce W. Dearstyne discuss his forthcoming book The Crucible of Public Policy: New York Courts in the Progressive Era (SUNY Press). He writes that it demonstrates that “New York’s high court was more progressive than many of its state counterparts or the U.S. Supreme Court at that time.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's library is up for auction (The Guardian). That reminds us to say that Georgetown Law has Charles E. Wyzanski, Jr.'s books, with much often fascinating marginalia.Wyzanski, 1937 (LC)

- Frank G. Colella reviews The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation 1760-1840, by Akhil Reed Amir, in the New York Law Journal.

- In The Times of India, January 20, 2022, Jehosh Paul, an LL.M in Law and Development candidate at the Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, has published a brief response to what we take to be Elizabeth Kolsky’s Codification and the Rule of Colonial Difference: Criminal Procedure in British India, Law and History Review 23 (Fall 2005): 631-683.

- New online from Law and History Review and Cambridge Core: Bengal Regulation 10 of 1804 and Martial Law in British Colonial India, by Troy Downs.

- ICYMI: Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw on Martin Luther King as CRT theorist avant la lettre (LA Times). A report on the exhibition of the Historical Society of the New York Courts on the Lemmon Slave Case (Lohud). The Strange History of Kansas's liquor laws (Flatland).

Weekend Roundup is a weekly feature compiled by all the Legal History bloggers.

Friday, January 21, 2022

Ranney's Social History of American Tort Law

Joseph A. Ranney has published The Burdens of All: Social History of American Tort Law (Carolina Academic Press, 2021). Front matter, including TOC and Introduction, is here.

Tort law, the law of how the costs of accidents and other harms should be allocated, is part of America’s larger story of social conflict and progress. The Burdens of All is the first book to fully recount tort law’s place in that story.--Dan Ernst

The book describes the law’s struggle to move from nineteenth-century individualism, which required accident victims to shift for themselves and protected corporations, to the view that accidents are an inevitable part of modern industrial society and must be paid for by society as a whole. Also, the book paints vivid pictures of the judges and social reformers who have shaped tort law’s course; the current struggle between individualism and socialization; and the historical struggle over the proper balance of power between judges and juries in tort cases. Its wealth of information and insights will intrigue law- and social-history devotees alike.

Bessler's "Private Prosecution in America"

John D. Bessler, University of Baltimore School of Law, has published Private Prosecution in America: Its Origins, History, and Unconstitutionality in the Twenty-First Century, with Carolina Academic Press:

Private Prosecution in America is the first comprehensive examination of a practice that dates back to the colonial era. Tracking its origins to medieval times and the English common law, the book shows how “private prosecutors” were once a mainstay of early American criminal procedure. Private prosecutors—acting on their own behalf, as next of kin, or though retained counsel—initiated prosecutions, presented evidence in court, and sought the punishment of offenders.The front matter, including the TOC and Introduction, is here.

Until the rise and professionalization of public prosecutors’ offices, private prosecutors played a major role in the criminal justice system, including in capital cases. After conducting a 50-state survey and recounting how some locales still allow private prosecutions by interested parties, the book argues that such prosecutions violate defendants’ constitutional rights and should be outlawed.

--Dan Ernst

Thursday, January 20, 2022

Cambridge Seeks an Assistant Professor of Legal History

The Faculty of Law is seeking to appoint an appropriately qualified person to a University Assistant Professorship in Legal History from 1 October 2022. The person appointed will teach at undergraduate and postgraduate level, conduct and supervise research, and participate in the general work of the Faculty.

The appointee will be an outstanding scholar and teacher in Legal History and will demonstrate potential to carry out and publish research of the highest calibre. The person appointed will normally hold a PhD or equivalent qualification. The appointee will be based in central Cambridge. The appointment will be permanent, subject to a probationary period of five years.

In exceptional circumstances, it may be possible to offer a supplement to the salary range stated for this role of up to 20%. Any such supplement would be awarded on the basis of a demonstrable history of outstanding achievement and an expected future level of contribution and is entirely at the discretion of the University.

We particularly welcome applications from candidates from a BME background for this vacancy as they are currently under-represented at this level in our Faculty. More.

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

Moral Regulation of "Economy" in the Early Modern Atlantic World

[We have the following announcement. DRE]

Symposium on Comparative Early Modern Legal History: Law, Theology, and the Moral Regulation of "Economy" in the Early Modern Atlantic World. Friday, March 25, 2022. Newberry Library, Chicago.

The time is long past when the Western world's emergent commercial culture could be understood solely in terms of a Protestant ethos or the division between commerce and social morality occasioned by the Protestant Reformation. Scholarship has shown that "modern" ideas regarding commerce and "economics" had their roots in late-medieval Catholic thought and in neo-scholastic ideas that blended theology, justice, and law. It is clear as well that the rise of commercial thinking was not a linear intellectual development. Protestants and Catholics alike, facing the moral and social implications of novel "economic" relations, undertook deep theological and legal reflections regarding unbridled, competitive, exchange-oriented gain seeking. Many of these concerns were raised in the context of Europe's westward expansion to the New World. Usury, just price, interest, legal personality, slavery, reciprocity, property, cases of conscience, doubts regarding self-regulating mechanisms, concerns for the poor-all figured in a vibrant legal discourse that simultaneously elaborated and critiqued a set of ideas regarding human economy that became dominant between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. This conference will bring together historians, legal scholars, and social scientists to investigate law's historical role in enabling and regulating behaviors now recognized as foundational to modern economies.

Brian Owensby (University of Virginia) and Richard Ross (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) organized "Law, Theology, and the Moral Regulation of 'Economy' in the Early Modern Atlantic World." The conference is an offering of the Symposium on Comparative Early Modern Legal History, which gathers every other year at the Newberry Library in Chicago in order to explore a particular topic in the comparative legal history of the Atlantic world in the period c.1492-1815. Funding has been provided by the University of Illinois College of Law.

Attendance at the Symposium is free and open to the public. Those who wish to attend should preregister by sending an email to Richard Ross at Rjross@illinois.edu. Papers will be circulated electronically to all registrants several weeks before the conference.

For information about the conference, please consult our website or contact Richard Ross at Rjross@illinois.edu or at 217-244-7890.

[Schedule after the jump.]

Monday, January 17, 2022

Swanson on Black Women Inventors

Kara W. Swanson, Northeastern University School of Law, has posted Inventing While a Black Woman: Passing and the Patent Archive, which is forthcoming in the Stanford Technology Law Review:

This Article uses historical methodology to reframe persistent race and gender gaps in patent rates as archival silences. Gaps are absences, positioning the missing as failed non-participants. By centering Black women and letting the silences fill with whispered stories, this Article upends our understanding of the patent archive as an accurate record of US invention and reveals powerful truths about the creativity, accomplishments, and patent savviness of Black women and others excluded from the status of “inventor.” Exposing the patent system as raced and gendered terrain, it argues that marginalized inventors participated in invention and patenting by situational passing. It rewrites the legal history of the true inventor doctrine to include the unappreciated ways in which white men used false non-inventors to receive patents as a convenient form of assignment. It argues that marginalized inventors adopted this practice, risking the sanction of patent invalidity, to avoid bias and stigma in the patent office and the marketplace. The Article analyzes patent passing in the context of the legacy of slavery and coverture that constrained all marginalized inventors. Passing, while an act of creative adaptation, also entailed loss. Individual inventors gave up the public status of inventor and also, often, the full value of their inventions. Cumulatively, the practice amplified the patent gaps, systematically overrepresenting white men and thus reinforcing the biases marginalized inventors sought to avoid. The Article further argues that false inventors were used as a means of appropriating the inventions of marginalized inventors. This research provides needed context to the current effort to remedy patent gaps. Through its intersectional approach, it also brings patent law into broader conversations about how law has supported systemic racism and sexism and contributed to societal inequality.--Dan Ernst

Saturday, January 15, 2022

Weekend Roundup

- Congratulations to Myisha Eatmon (University of South Carolina), who will join the departments of History and African and African American Studies at Harvard University! (via Twitter)

- From the Washington Post's "Made by History" section: Orville Vernon Burton (Clemson University) and Armand Derfner (Charleston School of Law), "Texas’s new attempt to circumvent the Constitution resurrects an old tactic"; Carole Joffe (University of California, San Francisco), "Failing to embed abortion care in mainstream medicine made it politically vulnerable."

- "Nine decades later, W.E.B. Du Bois’s work faces familiar criticisms": Martha S. Jones, Johns Hopkins University, on Black Reconstruction (WaPo).

- "Rescuing MLK and his Children’s Crusade": a excerpt from the forthcoming Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality by Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Harvard University (Harvard Gazette).

- New online from Law and History Review and Cambridge Core: Hanging Matters: Petty Theft, Sentence of Death, and a Lost Statute of Edward I, by Henry Summerson.

- George William Van Cleve explores “what he sees as the flaws in the United States Constitution,” in conversation with William Treanor, dean of Georgetown Law, in a virtual program was hosted by James Madison’s Montpelier in Virginia.

- From In Custodia Legis, news of a new Library of Congress acquisition: "A 14th-Century Manuscript of Registrum Brevium."

Weekend Roundup is a weekly feature compiled by all the Legal History bloggers.

Friday, January 14, 2022

Munshi on Dispossession and the Property Law Tradition

Sherally Munshi, Georgetown University Law Center, has posted Dispossession: An American Property Law Tradition, which appears in the Georgetown Law Journal:

Universities and law schools have begun to purge the symbols of conquest and slavery from their crests and campuses, but they have yet to come to terms with their role in reproducing the material and ideological conditions of settler colonialism and racial capitalism. This Article considers the role the property law tradition has played in shaping and legitimizing regimes of racialized dispossession past and present. It intervenes in the traditional presentation of property law by arguing that dispossession describes an ongoing but disavowed function of property law. As a counter-narrative and critique of property, dispossession is a useful concept for challenging existing property arrangements, often rationalized within liberal and legal discourse.–Dan Ernst

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Woolhandler on Parillo on Taxation and the Nondelegation Doctrine

Ann Woolhandler, University of Virginia School of Law, has posted Public Rights and Taxation: A Brief Response to Professor Parrillo:

A division exists between scholars who claim that Congress made only limited delegations to executive officials in the early Republic, and those who see more extensive delegations. In A Critical Assessment of the Originalist Case Against Administrative Regulatory Power: New Evidence from the Federal Tax on Private Real Estate in the 1790s, Professor Nicholas Parrillo claims that congressional delegations under the direct tax of 1798 undercut arguments that early delegations of rulemaking either addressed unimportant issues or were limited to special categories. Nondelegation scholar Professor Ilan Wurman responded to Parrillo in the volume of the Yale Law Journal in which Parrillo’s article appeared, particularly arguing that Congress itself addressed the important issues as to the 1798 tax. This paper instead focuses on Parrillo’s claim that the 1798 tax did not fall within any limited special category for nondelegation purposes. Admittedly, Parrillo’s evidence undermines some generalizations that early rulemaking was not “coercive and domestic.” Taxation, however, falls into the category of public rights, which could include matters that were domestic and coercive, but that nevertheless allowed for a more lenient application of separation of powers strictures.

--Dan Ernst

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

Blue, "The Deportation Express: A History of America through Forced Removal"

The University of California Press has published The Deportation Express: A History of America through Forced Removal, by Ethan Blue (University of Western Australia). A description from the Press:

A history of the United States' systematic expulsion of "undesirables" and immigrants, told through the lives of the passengers who travelled from around the world, only to be locked up and forced out aboard America's first deportation trains.

The United States, celebrated as a nation of immigrants and the land of the free, has developed the most extensive system of imprisonment and deportation that the world has ever known. The Deportation Express is the first history of American deportation trains: a network of prison railroad cars repurposed by the Immigration Bureau to link jails, hospitals, asylums, and workhouses across the country and allow forced removal with terrifying efficiency. With this book, historian Ethan Blue uncovers the origins of the deportation train and finds the roots of the current moment, as immigrant restriction and mass deportation once again play critical and troubling roles in contemporary politics and legislation.

A century ago, deportation trains made constant circuits around the nation, gathering so-called "undesirable aliens"—migrants disdained for their poverty, political radicalism, criminal conviction, or mental illness—and conveyed them to ports for exile overseas. Previous deportation procedures had been violent, expensive, and relatively ad hoc, but the railroad industrialized the expulsion of the undesirable. Trains provided a powerful technology to divide "citizens" from "aliens" and displace people in unprecedented numbers. Drawing on the lives of migrants and the agents who expelled them, The Deportation Express is history told from aboard a deportation train. By following the lives of selected individuals caught within the deportation regime, this book dramatically reveals how the forces of state exclusion accompanied epic immigration in early twentieth-century America. These are the stories of people who traveled from around the globe, only to be locked up and cast out, deported through systems that bound the United States together, and in turn, pulled the world apart. Their journey would be followed by millions more in the years to come.

Praise from reviewers:

"Exciting and original, this book is a significant contribution at the forefront of US history and immigration history. It examines the displacement and erasure of people of color in the nation-building project of white Americans beyond the colonial period. Using never-before-seen immigration officials' communications and correspondence, the memoirs of a physician hired on the deportation trains, employee records, train itineraries, and passenger lists, this book even opens up the experience of deportees as well as those of the middle managers and agents who made the state real."—Torrie Hester

"This book describes one of the first—but little known—steps taken by the federal government to systematize the deportation of immigrants who violated the rules governing their lives and work in the United States. This first step illustrates how and on what grounds the criminalization and incarceration of immigrants began. I know of no other competing works. This is, I believe, the first study of deportation trains, and it's very important and original as such."—Donna Gabaccia

More information is available here. An interview with the author is available here, at New Books Network.

-- Karen Tani

Tuesday, January 11, 2022

Hannay on the Statute of Marlborough

Ashley Hannay, Lecturer in Property Law, University of Manchester, has posted the prepublication draft of his article "By fraud and collusion": Feudal Revenue and Enforcement of the Statute of Marlborough, 1267-1526, which appeared in the Journal of Legal History 42 (2021): 69:

Following the Statute of Marlborough, 1267, feoffments which were designed to deprive lords of wardship could in some circumstances be deemed "collusive" or "fraudulent." This was further complicated from the mid fourteenth century onwards by the common practice of creating uses to circumvent the common law rules prohibiting the devise of land by last will. The effect of uses being created to perform last wills was that lords, in particular the king, were losing out on their feudal incidents. The current view, put forward by legal historians, is that the crown struggled to enforce the Statute of Marlborough after 1410, and that the ‘campaign’ against this loss of feudal revenue began in the 1520s. This paper seeks to re-examine this view, particularly in relation to how Marlborough and collusion were understood and the crown’s approach to the avoidance of feudal incidents in the reign of King Henry VII.--Dan Ernst

CFP: "Stabilising Regimes of Normativity" in the Iberian Worlds

[We have the following call for papers for the conference Change over time in the Iberian Worlds: stabilising regimes of normativity. DRE]

The Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory’s Glocalising Normativities project aims to construct a global history of normative production by studying the interaction of local processes of the cultural translation of normative knowledge within global networks in the early modern Iberian worlds.

For the project’s 2022 Annual Conference and the resulting publication, we are looking for contributions focusing on legal change and stability in any region of the Portuguese and Spanish empires in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas during the early modern period. We want to explore how legal history can offer a particular perspective for understanding legal change. Discussions of case studies, comparisons, long-term perspectives as well as methodological and analytical approaches – particularly in conversation with the long-standing tradition of discussions on legal change – are welcome. A detailed description of the conference’s topic and its conceptual framework can be found in the full text of the Call.

The selected papers will first be discussed as drafts in a virtual meeting to be held in April 2022. The final papers will be discussed in person (should the pandemic situation allow) in Frankfurt am Main at the Glocalising Normativities Annual Conference on 19–21 October 2022, and subsequently submitted for publication in the Brill series Max Planck Studies in Global Legal History of the Iberian Worlds. The deadline for submission of proposals is the 15th of January 2022.

Monday, January 10, 2022

Property, Religion and State Formation in the Meiji Constitution

[We have the following announcement from the Asian Legal History Seminar Series. DRE]

Property, Religion, and State Formation: The Meiji Constitution in the Context of East Asian History

Speaker: Professor Kentaro Matsubara (University of Tokyo)

Respondent: Professor Kevin YL Tan (National University of Singapore)

This presentation discusses some wider significances of the Japanese Constitution of 1889, by looking into its implications in the social changes of the time, both domestically and internationally. It begins by focusing on the relationships between the protection of property and the formation of the state in Tokugawa Japan and Qing China, highlighting the differences in the roles of what we might call religious beliefs. The protection of the private property is seen as a basic function of the modern sovereign state. However, before Japan was reformulated into modern a sovereign state through such processes as the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution, the relationships between state bureaucracy and property regimes functioning at the level of local communities was far more complex than envisaged in such a modern state. Moreover, it greatly differed from the state of affairs in traditional Chinese society. This paper looks into these differences, the different relationships between state bureaucracy and local communities, and the different formations of local communities, in turn tightly connected to roles of religious beliefs and religious power. In conclusion, it will be discussed how the differences in traditional social formation would influence the ways in which China and Japan would integrate themselves into the Westphalian system of sovereign states in the 19th century.

Date: Friday 14th January 2022. Time: 3:00 – 4:30pm (HK TIME) Via Zoom. All are welcome, but registration is required, via this link.]

Conveners

Dr. Michael Ng (HKU Faculty of Law)

Dr. Alastair McClure (HKU Department of Histor

Saturday, January 8, 2022

Weekend Roundup

- The latest newsletter of the Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of Watergate.

- Matthew Waxman, Columbia Law School, on "Remembering the Selective Draft Law Cases" (Lawfare).

- The Federal Judicial Center's History Office recaps its work in 2021 in this thread.

- The Northwestern University professors Michael Allen, Kevin Boyle, Kate Masur, and Alvin B. Tillery Jr. on January 6.

- "Twelve Tables Press announces ... its newest publication, American Lawyer: Twelve Attorneys Who Have Transformed the United States, written by attorney and Arizona State University Professor Gary L. Stuart." More.

- From the Washington Post's "Made by History" section: Leon Fink (drawing upon Steven F. Lawson) on how Progressive-era reformers looked beyond court-packing for reforms of the Supreme Court. (See also William Ross's A Muted Fury. )

- Which reminds us: Chief Justice Roberts's recent invocation of William Howard Taft and federal judicial administration has elicited comment by Steven Lubet, Northwestern Law, on NBCNews and Matt Ford in the New Republic.

- ICYMI: A pardon for Homer Plessy (MSNBC; Time). “A tentative agreement to transfer ownership of [Richmond's] now mostly removed Confederate monuments to the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia” (Virginia Lawyers Weekly). "90 years on: Remembering the Scottsboro Boys" (Alabama Political Reporter).

Weekend Roundup is a weekly feature compiled by all the Legal History bloggers.

Friday, January 7, 2022

CFP: Asian Legal History Conference

This is a gentle reminder that the submission deadline is 14 January 2022.

The Asian Legal History Association is accepting submissions for the 2nd Asian Legal History Conference, to be held from 23 to 24 July 2022. We invite you to submit an abstract on any subject under the general theme of "legal history in Asia." The length of the abstract should be between 100-250 words. Authors who have been chosen to present their abstracts will be contacted on 28 January 2022. To make a submission and find out more about the Conference, please visit our website (below). For inquiries, please contact alha.contact@gmail.com.

We look forward to your submissions and contributions to the study of Asian legal history. For more information, kindly check out our website and LinkedIn page.

Swain on Contract in 19th-Century New South Wales

Warren Swain, University of Auckland Faculty of Law, has posted The Laws of "An Old and Settled Society"? The Law of Contract in New South Wales in the Mid-Nineteenth Century:

The history of contract law in New South Wales in the decades after the closure of the Court of Civil Jurisdiction in 1814 hasn’t received much attention from legal historians. This is an important omission. At the heart of this story is a simple but critical inquiry about the way in which the law of contract in the colony mirrored or diverged from the law of contract that applied back in London. This was rarely a matter that judges addressed explicitly. Piecing together the relationship is an exercise in reconstruction. This can only be done by examining the body of case law. The creation of the Australasian Colonial Legal History Library combined with readily searchable newspaper reports has made this task easier. The evidence in the mid-nineteenth century is still sometimes sketchy. Context is relevant. The colony moved from a quasi-military penal colony to a significant hub of commercial activity. The period also saw a shift in the legal system as the old informal systems evolved into a much more legalistic one. Some issues like the desertion of sailors demanded local solutions. In fact there are a range of examples in which well-established English contract doctrine did not necessarily fit very well with the conditions of the colony.--Dan Ernst

Thursday, January 6, 2022

Scipio Africanus Jones, 1863/4-1943

[As I mentioned yesterday, the second of the two essays in my exam in my legal history course is biographical. This year's follows; for earlier exams' essays, start here.]

|

| Scipio A. Jones (wiki) |

Scipio Africanus Jones (1863/4-1943), named after a Roman general who won great battles in North Africa, was born in Arkansas to Jemima Jones, a nineteen-year-old enslaved woman, in either 1863 or 1864, but, in any event, while the doctor possessing her as guardian for an under-aged owner fled advancing Union forces during the Civil War. Light-skinned-he was the only member of his household listed as mulatto in the 1880 census-Jones was thought to be the doctor’s son, who was said to have paid for Jones’s education. He grew up in rural Arkansas, where he worked on farms, attended all-Black schools, and was the only member of his household listed as literate in the 1870 census. In his late teens, he moved to Little Rock, the state capital and Arkansas’s largest city, where he attended a Blacks-only preparatory academy and college while living in the home of a White man and working on the man’s nearby farm. From 1885 until at least 1887, he taught school while readying himself for a legal career. He applied to the University of Arkansas’s law school, which had never admitted a Black student, but was rejected--as was his offer to serve as the law school’s janitor if he could attend lectures. Instead, Jones studied in the law offices of three prominent White lawyers in Little Rock, one a federal judge.

In June 1889, after being examined by a committee of eminent lawyers, he was admitted to practice in the courts of the county in which Little Rock is located. Forty years later, in an address to the National Bar Association, he hinted that when he started out the Black bar left much to be desired. In those days, he explained, the “greatest endowment of the budding lawyer was the gift of speech and resounding rhetoric,” not “quiet, persistent, patient and laborious research into the mysteries and principles of the law.” Further, Black lawyers “had not become thoroughly imbued” with the ideal that their own interests should “fade into insignificance” next to those of their clients.

When Jones entered the legal profession, Republicans, relying on Black voters, who made up 37 percent of the state electorate, still contested Democrats for elective office. After Democrats won the governorship and control of the statehouse in 1890, however, a series of laws disenfranchised many of the state’s Blacks. The state Republican Party divided into a “Lily White” faction that excluded African Americans, and a “Black and Tan” faction that continued the biracialism of the Reconstruction era. As a leader of the Black and Tans, Jones helped send an alternate, biracial slate from Little Rock to the Republican state convention in 1900, served as an Arkansas delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1912, helped organize rival state Republican conventions in 1914 and 1916, and, in 1920, led Black Republicans into a Whites-only hotel where the Lily Whites were convening. In 1924, a compromise between the two factions was reached, under which Jones represented Arkansas in Republican National Conventions in 1928 and 1940.

Jones’s first professional association was the National Negro Business League (NNBL), founded in 1900 by Booker T. Washington, who served as its president. From the start, lawyers were members, if only because so many were also real estate brokers and bankers. In Little Rock in 1909, Jones helped found, as an auxiliary of the NNBL, the National Negro Bar Association (NNBA) and became its first treasurer. Many of the South’s Black lawyers joined the NNBA, but northern Black lawyers did not, because of the group’s association with Booker T. Washington. (They would establish their own “National Bar Association” in 1924.)

In 1891 Jones and another lawyer unsuccessfully opposed legislation segregating railroad cars in the state. In 1901 he won reversals from the Arkansas Supreme Court of two criminal convictions on the ground that he should have been allowed to prove that Blacks had been excluded from the state’s juries. (On remand, neither challenge succeeded.) And in 1905 he successfully fought to change a law that unfairly extended the time convicts needed to work off their fines.

At first, Jones’s law practice consisted overwhelmingly of domestic relations and criminal defense, including the court-appointed representation of the indigent. Over the course of his career, eleven of his criminal cases went to the Arkansas Supreme Court. But Jones soon acquired a substantial practice representing a variety of Black fraternal organizations when members sued to collect on their life insurance policies. His biggest client was the Mosaic Templars of America, headquartered in Little Rock, whose membership ultimately numbered 80,000 and for whom he became “national attorney general” around 1895. By 1928, an African American newspaper would call him “the mainstay of Negro business in Arkansas.”

Wednesday, January 5, 2022

Aviation, 1903-1948

[The exam in my American legal history course consists of two essays, one on the legal history of some regulatory regime my students did not study but which developed much like those they did. The other is a biographical essay on some Black, Jewish, and/or female lawyer who made for an interesting comparison with those we studied. Below is a slightly augmented version of the first essay from this year's exam. For earlier ones, start here. DRE.]

Although the world’s first powered flight took place in the United States on December 17, 1903, when Orville Wright flew 120 feet on a North Carolina barrier island, for many years the U.S. lagged behind other nations in promoting and regulating aviation. As an American treatise writer observed, while Americans still regarded aviation as “a very dangerous sport carried on by the more adventurous barnstormers of the day,” Europeans had taken it seriously as “a war weapon and a means of fast transportation knowing no national boundaries.” Their governments directly regulated air transportation and placed civilian and military aviation under a single, national Ministry of Aviation. In contrast, the United States did not even begin scheduled air mail service until 1918. Two more years passed before transcontinental air service arrived, with night flights guided by bonfires.Indeed, well into the 1920s, American jurists still had not cleared the most fundamental legal hurdle to commercial flight, the maxim Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos (“Whoever owns the soil, owns to the heavens and to the depths”). If followed strictly, a commentator observed, the ad coelum maxim would “create a private property right in the airspace, placing absolute ownership to the heavens in the surface owner.” Aviators would not be able to negotiate with the countless surface owners whose airspace they crossed and would therefore face “continual litigation in trespass.” Conferring eminent domain power on airlines also was no solution, if only because weather commonly forced aviators to depart from their flight plans.

American lawyers set out to solve this law-made problem. Soon after World War I, a committee of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws started work on a model statute. Approved by the American Bar Association in 1922, it legalized flight over the land of others unless it occurred “at such low altitudes as to interfere with the then existing use to which the land . . . or the space above the land . . . is put by the owner.” In 1923, a Minnesota trial judge reached the same result without a statute. The ad coelum maxim, wrote Judge J. C. Michael, was “adopted in an age of primitive industrial development . . . when any practical use of the upper air was not considered or thought possible.” But now, thanks to “marvelous . . . mechanical inventions,” the “great public usefulness” of air travel was obvious to all. “Modern progress and great public interest should not be blocked by unnecessary legal refinements,” he declared. Courts had long adapted common-law rules to “new conditions arising out of modern progress”; now they should recognize that “the upper air is a natural heritage common to all of the people.”

A single federal agency charged with regulating all aspects of civilian aviation did not arrive until 1938. Until then, two different federal departments-and, briefly, an existing independent commission-imperfectly set aviation policy.

|

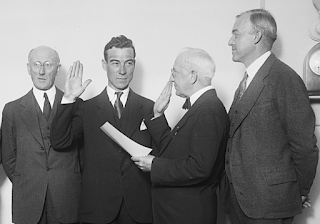

| MacCracken, right, observes his successor's swearing-in (LC) |

Starting in 1922, Secretary Herbert Hoover lobbied for the creation of a bureau within the Department of Commerce to regulate civilian aviation. Congress finally obliged with the Air Commerce Act of 1926, which empowered the Secretary of Commerce to a register and inspect aircraft, examine and rate pilots, certify airports, and promulgate safety regulations. It also created an “Aeronautics Branch” within the Commerce Department, headed by an Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics, nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The first holder of that office was William MacCracken, a 1911 graduate of the University of Chicago Law School, who had served as a flight trainer during World War I, had chaired the American Bar Association’s Committee on the Law of Aeronautics since its creation in 1920, and helped draft the Air Commerce Act after studying European air ministries. “The great deal of discretion” the statute vested in the Commerce Department, MacCracken said, was necessary if its regulations were to “keep pace with the development of this new art.” Although some aviation lawyers, hoping to end competition from small “fly by night” air carriers, argued that the Air Commerce Act gave Hoover the power to establish price-and-entry regulation for the industry by issuing a limited number of “certificates of convenience and necessity” to air carriers for particular routes and setting the prices they could charge passengers, MacCracken could never persuade Hoover to take that step, probably because Hoover wanted the industry to organize itself through its own associations.

Saturday, January 1, 2022

Weekend Roundup

- Episode 8 of the podcast Advocates features legal historian Carlton Larson (UC Davis Law). He "describes how the Founding Fathers of America, John Adams, Thomas

Jefferson, and James Wilson, were as lawyers and advocates. He also dips

into the career of Abraham Lincoln as lawyer and advocate."

- Over at Notice & Comment, the blog of the Yale Journal on Regulation and ABA Section of Administrative Law & Regulatory Practice, Eli Nachmany, a J.D. candidate at the Harvard Law School, has posted Evaluating the History of D.C. Circuit Judges Who Headed Agencies in Light of Judge J. Michelle Childs's D.C. Circuit Nomination.

- University of Chicago Federalist Society has created a writing prize for “members of the Federalist Society anywhere in the country so long as they do not have an extensive history of academic publication.” This year's topic: “Does originalism still work?” (H/t: Will Baude in The Volokh Conspiracy.)

- New online (and ungated) from Law and History Review and Cambridge Core: Policing Jim Crow America: Enforcers’ Agency and Structural Transformations, by Anthony Gregory. It is “a critical historiographical essay animated by the research question of how the decisions of police and sheriffs illuminated and drove the transformation of white supremacy through different forms from emancipation to the end of Jim Crow segregation.”

- The Historical Society of the New York Courts is sponsoring From Stonewall to Windsor: New York’s March to LGBTQ Rights, a free in-person (at this writing) and online event at the New York City Bar Association, from 6:00 pm to 8:00 pm EST on January 13, 2022.

- From the Washington Post's "Made by History" section: Rachel Michelle Gunter, "You didn’t always have to be a citizen to vote in America"; Duncan Hosie, "With the Supreme Court lurching right, state courts offer liberals hope."

- Some legal history highlights from recent JOTWELL posts: Cary C. Franklin (UCLA Law) reviews Jonathan Gienapp's "Written Constitutionalism, Past and Present," which appeared in Volume 39 of the Law & History Review (2021); Lael Weinberger (Harvard Law School) reviews Stuart Banner, The Decline of Natural Law: How American Lawyers Once Used Natural Law and Why They Stopped (2021).

- Update: Here is Katharine Q. Seelye’s NYT obituary for Karen Ferguson, “director of the Nader-backed Pension Rights Center in Washington for more than four decades.”