Ideology, charisma, conformism, hatred, greed, and war were all very important, but each was related to the others and all mattered within rapidly changing historical circumstances. In his profound study Holocaust, Peter Longerich puts forward an analysis that includes all these factors and shows how politics or, as he puts it, Politik, set them all in motion. In this amplified English edition of his Politik der Vernichtung (1998), Longerich preserves the German term Judenpolitik, and with good reason. In German Politik means both “politics” and “policy,” and the compound noun (Juden + Politik) gives a sense of a joining of concepts that English cannot quite convey. In Longerich’s analysis, Judenpolitik has three meanings: German policy toward Jews; the national and international politics of the Jewish question; and the manner in which discrimination against Jews and then their extermination permeated German political life between 1933 and 1945.Ultimately, this "impressive study of Judenpolitik is not a detailed recounting of the Holocaust, and makes no claim to take account of the perspective of the Jews who died and the neighbors who watched, collaborated, or more rarely rescued. But it supplies the best account we have of the relationship between anti-Semitism and mass murder, and conveys a melancholy plausibility."

Read the rest here.

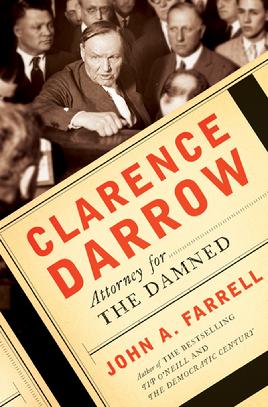

Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned, by John A. Farrell is a "clear-sighted, empathetic biography," Wendy Smith writes in the Los Angeles Times. Darrow was "a towering figure in U.S. jurisprudence and politics. He served as defense lawyer for the people most hated and feared by respectable society and was indeed, as his friend Lincoln Steffens wrote in 1932, an 'attorney for the damned.'" Darrow was "no left-wing saint. He was always in need of money and agreed to defend gangsters, bootleggers and crooked politicians for large fees." Yet he was devoted to "imperfect, troubled humanity. 'We are all poor, blind creatures bound hand and foot by the invisible chains of heredity and environment, doing pretty much what we have to do in a barbarous and cruel world,' he declared. 'That's about all there is to any court case.'" Continue reading here.

MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD: “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and the Battle for America by David S. Reynolds is an "informative account of the writing, reception and modern reputation of 'Uncle Tom’s Cabin," Andrew Delbanco writes in the New York Times. "Reynolds unstintingly celebrates its author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, as a colossal writer who mobilized public opinion against slavery, and proved, against long odds, 'a white woman’s capacity to enter into the subjectivity of black people.'" Delbanco finds the author to be a "rewarding researcher," even as he suggests that Reynolds goes too far in his conclusions. Ultimately,

Read the rest here.we are left at the end of this book with the unsettling question of how to think about “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” as part of our cultural inheritance. The case for it as a literary work of depth and nuance is dubious. Yet it belongs to the very short list of American books (including, say, “The Other America” by Michael Harrington and “Silent Spring” by Rachel Carson) that helped create or consolidate a reform movement — in Stowe’s case, the most consequential reform movement in our history. Perhaps the fact that readers today have trouble taking seriously its heroes and villains is a tribute to its achievement — since, in some immeasurable way, it helped bring on the war that rendered unimaginable the world that Stowe attempted to imagine.

Also this week, The Law of Life and Death by Elizabeth Price Foley is reviewed by Eric Posner in The New Republic's The Book; CAMBODIA’S CURSE: The Modern History of a Troubled Land by Joel Brinkley is reviewed in the New York Times.