in or about the years between 1640 to 1760 men were increasingly viewed as public beings and women as private ones. Her book presents case studies (in five chapters and four interludes) from both sides of the English-speaking Atlantic world to argue for a fundamental shift in definitions of political capacity.Initially, status mattered more than gender, so that female aristocrats could sometimes vote and participate in political affairs. "But by the end of the book, even female aristocrats had been shooed home and their views of public affairs reduced to tea-table gossip. Politics was now a masculine preserve."

Norton examines published and unpublished writing, showing that a "tightening verbal associations — 'public' equals men and 'private' equals women" becomes prevalent. Chopin finds her sources to be "rich," but thinks that the author "goes after them with the equivalent of a power tool that has lost its edge." After "at least a generation of women’s historians" have explored the concept of separate spheres, many "have concluded that any notion of a complete separation is misleading, because exceptions and crossovers were so frequent," Norton's examples "may match her analysis, but are they the only ones that existed?"

Read the rest here.

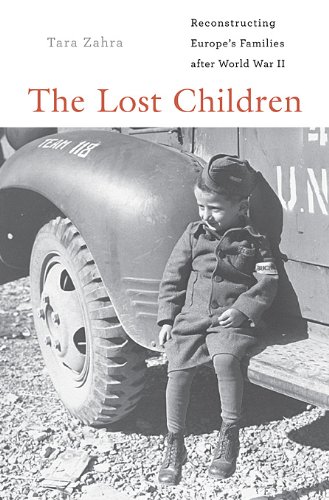

"Tara Zahra, a historian who made her name writing about the ambiguities of nationality in Czechoslovakia, has now added an important contribution to the growing literature on Europe’s reconstruction after World War II," writes historian Mark Mazower in a review of Zahra's new book The Lost Children: Reconstructing Europe's Families After World War II in The Book (New Republic).

Children—what was happening to them as a result of the war, and what to do with them after it—turn out to have been at the epicenter of what she terms a “psychological Marshall Plan.” Through the arguments about children we come to learn much about postwar Europe’s state of mind. In fact, the intense debate about how to care for children and bring them whole out of the war’s devastation was already underway before the end of hostilities.The post-WW II years saw intense debates about whether to raise children "as self-reliant individuals, or...as part of a collective," and whether the collective should be the family or the nation. "With the credibility and the prestige of Europe’s nation-state model challenged by the experience of Nazi rule, most political activists keen to guarantee the rebirth of their nation at liberation regarded children as a precious resource."

During these years there were "two contradictory trends: on the one hand, the revival of a discourse of familialism that made the nuclear unit the core of social stability and ultimately turned the 1950s into the most conservative decade of the century; and on the other, the emergence of a new state activism that supervised parents and children alike, and intervened in unprecedented ways in their personal affairs." The most extreme form of intervention was kidnapping.

Mazower's terrific review makes clear that Zahar's contributions go well beyond the history of children ad the family, and that The Lost Children illuminates not only postwar reconstruction but also the contours of postwar European nationalism. Read the rest here.

Other reviews this week: in the Washington Post, a review of a book on Grover Cleveland's secret cancer surgery, The President Is a Sick Man: Wherein the Supposedly Virtuous Grover Cleveland Survives a Secret Surgery at Sea and Vilifies the Courageous Newspaperman Who Dared Expose the Truth by Matthew Algeo; THE STORM OF WAR: A New History of the Second World War by Andrew Roberts in the New York Times; Desert Hell: The British Invasion of Mesopotamia by Charles Townshend in The Book (New Republic); MEDICAL MUSES: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris by Asti Hustvedt in the New York Times.