Liberal subjectivity and its complications loom throughout nineteenth-century cultural and intellectual history. Owing largely to Scottish Common Sense, American thinkers posited a normative, but putatively descriptive, account of the human subject. The person was rational, discrete, and agentive. However, as many historians have shown, these assumptions were frequently challenged, and many people clearly did not fit this model. Of course, one point of this model was to exclude certain subjects, such as women, African Americans, and Native Americans. But there were other exceptions too, some of which were understood as less fixed states, like the drunkard, the monomaniac, or the lunatic. Scholars of American religion have shown some interest in these politics of personhood, especially as they relate to Christian anthropology and the influence of Protestant thought of American political forms. Antebellum reformers, for instance, thought carefully about vice and social responsibility as they worked for temperance and against prostitution. Social gospel leaders, in different terms, considered the role of modernization and industrialization amid perceived social breakdowns. Religious figures from all positions on slavery employed ideas about morality and mental capacity to forge their theological justifications. Educators acknowledged the importance of cultivating morality and worked to instill it in public schoolchildren while navigating the politics of nonsectarianism. These are all familiar topics. Less common in American religious studies, though no less important, are mundane but meaningful legal issues like insurance, wills, torts, and divorce. It was here, Susanna Blumenthal argues in Law and the Modern Mind, that philosophical, legal, and medical discourses about personhood, consciousness, agency, and rationality had salience. Blumenthal’s brilliant study of “the default legal person” locates these high-minded and thorny questions—What is a person? Who is rational? What is insanity? Wait, isn’t everyone a little irrational sometimes?—in courtrooms throughout the nineteenth century.Read on here.

Thursday, March 31, 2016

McCrary reviews Blumenthal, "Law and the Modern Mind"

We recently announced the publication of Susanna L. Blumenthal's Law and the Modern Mind: Consciousness and Responsibility in American Legal Culture (Harvard University Press). Via Religion in American History, we now have a review, by Charles McCrary (Florida State). Here's the first paragraph:

Meier on an Adverse Possession Landmark Case

Luke Meier, Baylor University Law School, has posted The Neglected History Behind Preble v. Maine Central Railroad Company: Lessons from the “Maine Rule” for Adverse Possession, which is forthcoming in the Hofstra Law Review

Under the “Maine Rule” for adverse possession, only possessors having the requisite intent can perfect an adverse possession claim. The Maine Rule has been consistently criticized. The history behind the adoption of the Maine Rule, however, and the purpose it was to serve, have been ignored. This Article fills that void. This inquiry leads to some surprising revelations about the Maine Rule. The Maine Rule was originally adopted so as to distinguish prior Maine cases rejecting adverse possession in mistaken boundary situations. The purpose behind the Maine Rule, then, was to enable — rather than prohibit — adverse possession. The history surrounding the adoption of the Maine Rule has contemporary value; this history powerfully demonstrates the pitfalls of using a claimant’s state of mind as part of an adverse possession analysis.

Geltzer's "Dirty Words and Filthy Pictures"

The University of Texas Press has published Dirty Words and Filthy Pictures: Film and the First Amendment, by Jeremy Geltzer, “an author and entertainment and intellectual property attorney.” Judge Alex Kozinski contributed a Foreword.

From the earliest days of cinema, scandalous films such as The Kiss (1896) attracted audiences eager to see provocative images on screen. With controversial content, motion pictures challenged social norms and prevailing laws at the intersection of art and entertainment. Today, the First Amendment protects a wide range of free speech, but this wasn’t always the case. For the first fifty years, movies could be censored and banned by city and state officials charged with protecting the moral fabric of their communities. Once film was embraced under the First Amendment by the Supreme Court’s Miracle decision in 1952, new problems pushed notions of acceptable content even further.

Dirty Words & Filthy Pictures explores movies that changed the law and resulted in greater creative freedom for all. Relying on primary sources that include court decisions, contemporary periodicals, state censorship ordinances, and studio production codes, Jeremy Geltzer offers a comprehensive and fascinating history of cinema and free speech, from the earliest films of Thomas Edison to the impact of pornography and the Internet. With incisive case studies of risqué pictures, subversive foreign films, and banned B-movies, he reveals how the legal battles over film content changed long-held interpretations of the Constitution, expanded personal freedoms, and opened a new era of free speech. An important contribution to film studies and media law, Geltzer’s work presents the history of film and the First Amendment with an unprecedented level of detail.

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Life & Law Panel Recap: "Violence and Resistance in Rural Communities"

[We’re grateful to Smita Ghosh, JD, Class of 2014, and PhD Candidate, American Legal History, at the University of Pennsylvania, for this thoughtful recap of a panel at the Life & Law in Rural America Conference.]

To continue our coverage of the interdisciplinary conference on law in rural communities, I’m reporting on the first panel, "Violence and Resistance in Rural Communities."

The panel began with Mia Brett (History, Stony Brook University)’s history of vigilantes in postbellum Montana. Vigilantism was an important component of Montana territory, even as formal legal institutions appeared in the area. In the 1860s, small towns were governed by local sheriffs, many of whom had criminal connections themselves. Unsatisfied with the formal criminal justice system, prominent business-owners, lawyers and community leaders joined vigilance committees These committees targeted thieves and gang-members, punishing even the most minor of crimes with death (one Montanan, who had been accused of public drunkenness, was hanged after unsuccessfully begging the committee to cut off his tongue). The vigilantes connected their barbarism to American identity, drawing on a regional history of warfare with Native Americans. Later, their accounts of vigilante activity reverberated in accounts like Mark Twain’s “Roughing It,” further cementing violence as an American tradition.

The panel began with Mia Brett (History, Stony Brook University)’s history of vigilantes in postbellum Montana. Vigilantism was an important component of Montana territory, even as formal legal institutions appeared in the area. In the 1860s, small towns were governed by local sheriffs, many of whom had criminal connections themselves. Unsatisfied with the formal criminal justice system, prominent business-owners, lawyers and community leaders joined vigilance committees These committees targeted thieves and gang-members, punishing even the most minor of crimes with death (one Montanan, who had been accused of public drunkenness, was hanged after unsuccessfully begging the committee to cut off his tongue). The vigilantes connected their barbarism to American identity, drawing on a regional history of warfare with Native Americans. Later, their accounts of vigilante activity reverberated in accounts like Mark Twain’s “Roughing It,” further cementing violence as an American tradition.

Jillian Jacklin (History, University of Wisconsin)’s “A Family Affair” is a study of labor activism among Wisconsin’s dairy farmers. Thrust into a particularly volatile market during the depression, the state’s dairy farmers organized in a “milk pool” and refused to sell their products to larger dairy companies. Resistance, like dairy farming itself, was truly a “family affair.” The women whose labor had sustained the industry worked organized working families at barn dances and picnics. As Jillian noted, these examples complicated the historiographical binary between productive and reproductive labor, giving even “turtle races” a radical meaning. (For people who, like me, had never heard of turtle racing, the sport is summarized here--scroll to “Danger” for a particularly interesting illustration of violence and resistance). Opposition to this direct action took the form of defamation--national media called the farmers greedy, blaming them for starving the nation--as well as tear gas from local sheriffs. Despite the defamers, the farmers offered free milk to hospitals, children and the poor, embracing Progressive-era while eschewing the experts and elites long associated with the period.

Tyler Davis (Religion, Baylor University) presented “Life Beyond Lynch Law: Imagining the Human and Utopia in Rural Texas,” his analysis of Sutton Griggs’ Imperium in Imperio in the context of the national non-response to lynching. Like his contemporary Ida B. Wells, Davis argued, Griggs recognized the collusion of the state in extralegal violence. Imperio is not merely an escapist utopia but an independent desire for a new society, animated by decolonial struggles and global networks of resistance. It is significant, too that Griggs located the society in rural Texas, which was far from the American metropole and had been contested since the Spanish-American war. In the rural periphery of empire Griggs could imagine a site of black independence outside of white supremacy.

Heath Pearson (Anthropology, Princeton University) presented his paper “The Carceral Outside: Living & Laboring in a NJ Prison Town,” with a narrative dynamism that, I’ve since learned, is typical of anthropologists. He related his ethnographic study of a New Jersey town (he calls it “Dayton”) that his home to one state and one federal prison facility. Heath’s interview agenda included members of the local police department, whose officers have been sued several times for beating and shooting local residents, in an interrogation room (“what have you learned?,” they grilled). In Heath’s assessment, the town’s elite made Dayton into a prison town, soliciting prison investment when the town’s factories closed. Furthermore, Heath argued, the town is an “incarcerating” place, since federal drug laws, exclusionary employment policies, and general capital abandonment keep the town’s residents “imprisoned” at the fringes of the formal economy and at the whims of an increasingly militarized police force.

As commentator Beth Lew-Williams observed, the four papers illustrated the state’s relationship with even extra-legal violence. Lew-Williams introduced a question that would be reiterated: what is the role of the rural? How do historical phenomena--progressivism, law-and-order, black resistance, the prison industrial complex--change in rural settings? We’d be stumbling on these questions (and the word “rural” itself) throughout the conference.

To continue our coverage of the interdisciplinary conference on law in rural communities, I’m reporting on the first panel, "Violence and Resistance in Rural Communities."

The panel began with Mia Brett (History, Stony Brook University)’s history of vigilantes in postbellum Montana. Vigilantism was an important component of Montana territory, even as formal legal institutions appeared in the area. In the 1860s, small towns were governed by local sheriffs, many of whom had criminal connections themselves. Unsatisfied with the formal criminal justice system, prominent business-owners, lawyers and community leaders joined vigilance committees These committees targeted thieves and gang-members, punishing even the most minor of crimes with death (one Montanan, who had been accused of public drunkenness, was hanged after unsuccessfully begging the committee to cut off his tongue). The vigilantes connected their barbarism to American identity, drawing on a regional history of warfare with Native Americans. Later, their accounts of vigilante activity reverberated in accounts like Mark Twain’s “Roughing It,” further cementing violence as an American tradition.

The panel began with Mia Brett (History, Stony Brook University)’s history of vigilantes in postbellum Montana. Vigilantism was an important component of Montana territory, even as formal legal institutions appeared in the area. In the 1860s, small towns were governed by local sheriffs, many of whom had criminal connections themselves. Unsatisfied with the formal criminal justice system, prominent business-owners, lawyers and community leaders joined vigilance committees These committees targeted thieves and gang-members, punishing even the most minor of crimes with death (one Montanan, who had been accused of public drunkenness, was hanged after unsuccessfully begging the committee to cut off his tongue). The vigilantes connected their barbarism to American identity, drawing on a regional history of warfare with Native Americans. Later, their accounts of vigilante activity reverberated in accounts like Mark Twain’s “Roughing It,” further cementing violence as an American tradition.Jillian Jacklin (History, University of Wisconsin)’s “A Family Affair” is a study of labor activism among Wisconsin’s dairy farmers. Thrust into a particularly volatile market during the depression, the state’s dairy farmers organized in a “milk pool” and refused to sell their products to larger dairy companies. Resistance, like dairy farming itself, was truly a “family affair.” The women whose labor had sustained the industry worked organized working families at barn dances and picnics. As Jillian noted, these examples complicated the historiographical binary between productive and reproductive labor, giving even “turtle races” a radical meaning. (For people who, like me, had never heard of turtle racing, the sport is summarized here--scroll to “Danger” for a particularly interesting illustration of violence and resistance). Opposition to this direct action took the form of defamation--national media called the farmers greedy, blaming them for starving the nation--as well as tear gas from local sheriffs. Despite the defamers, the farmers offered free milk to hospitals, children and the poor, embracing Progressive-era while eschewing the experts and elites long associated with the period.

Tyler Davis (Religion, Baylor University) presented “Life Beyond Lynch Law: Imagining the Human and Utopia in Rural Texas,” his analysis of Sutton Griggs’ Imperium in Imperio in the context of the national non-response to lynching. Like his contemporary Ida B. Wells, Davis argued, Griggs recognized the collusion of the state in extralegal violence. Imperio is not merely an escapist utopia but an independent desire for a new society, animated by decolonial struggles and global networks of resistance. It is significant, too that Griggs located the society in rural Texas, which was far from the American metropole and had been contested since the Spanish-American war. In the rural periphery of empire Griggs could imagine a site of black independence outside of white supremacy.

Heath Pearson (Anthropology, Princeton University) presented his paper “The Carceral Outside: Living & Laboring in a NJ Prison Town,” with a narrative dynamism that, I’ve since learned, is typical of anthropologists. He related his ethnographic study of a New Jersey town (he calls it “Dayton”) that his home to one state and one federal prison facility. Heath’s interview agenda included members of the local police department, whose officers have been sued several times for beating and shooting local residents, in an interrogation room (“what have you learned?,” they grilled). In Heath’s assessment, the town’s elite made Dayton into a prison town, soliciting prison investment when the town’s factories closed. Furthermore, Heath argued, the town is an “incarcerating” place, since federal drug laws, exclusionary employment policies, and general capital abandonment keep the town’s residents “imprisoned” at the fringes of the formal economy and at the whims of an increasingly militarized police force.

As commentator Beth Lew-Williams observed, the four papers illustrated the state’s relationship with even extra-legal violence. Lew-Williams introduced a question that would be reiterated: what is the role of the rural? How do historical phenomena--progressivism, law-and-order, black resistance, the prison industrial complex--change in rural settings? We’d be stumbling on these questions (and the word “rural” itself) throughout the conference.

AJLH 56:1

The American Journal of Legal History is now relaunched with the posting of the special issue: The Future of Legal History 56:1 (March 2016).

The American Journal of Legal History is now relaunched with the posting of the special issue: The Future of Legal History 56:1 (March 2016).Introducing the Future of Legal History: On Re-launching the American Journal of Legal History

Alfred L. Brophy and Stefan Vogenauer

The Future of Legal History: Roman Law

Ulrike Babusiaux

The Future of the History of Medieval Trade Law

Albrecht Cordes

Constitutional Meaning and Semantic Instability: Federalists and Anti-Federalists on the Nature of Constitutional Language

Saul Cornell

A Context for Legal History, or, This is not your Father’s Contextualism

Justin Desautels-Stein

If the Present were the Past

Matthew Dyson

For a Renewed History of Lawyers

Jean-Louis Halpérin

Is it Time for Non-Euro-American Legal History?

Ron Harris

A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe

Phillip Hellwege

Legal History as Political Thought

Roman J. Hoyos

Constitution-making in the Shadow of Empire

Daniel J. Hulsebosch

First the Streets, Then the Archives

Martha S. Jones

The Constitution and Business Regulation in the Progressive Era: Recent Developments and New Opportunities

Paul Kens

Expanding Histories of International Law

Martti Koskenniemi

Sir Ivor Jennings’ ‘The Conversion of History into Law’

H. Kumarasingham

Federalism Anew

Sara Mayeux and Karen Tani

Law, Culture, and History: The State of the Field at the Intersections

Patricia Hagler Minter

The Future of Digital Legal History: No Magic, No Silver Bullets

Eric C. Nystrom and David S. Tanenhaus

Writing Legal History Then and Now: A Brief Reflection

Kunal M. Parker

Beyond Backlash: Conservatism and the Civil Rights Movement

Christopher W. Schmidt

Beyond Methodological Eurocentricism: Comparing the Chinese and European Legal Traditions

Taisu Zhang

Bennion and Jaffe, eds., "The Polygamy Question"

New from Utah State University Press: The Polygamy Question, edited by Janet Bennion (Lyndon State College) and Lisa Fishbayn Joffe (Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Brandeis University). Here's a description from the Press:

The practice of polygamy occupies a unique place in North American history and has had a profound effect on its legal and social development. The Polygamy Question explores the ways in which indigenous and immigrant polygamous practices have shaped the lives of individuals, communities, and the broader societies that have engaged with it. The book also considers how polygamy challenges our traditional notions of gender and marriage and how it might be effectively regulated to comport with contemporary notions of justice.

The contributors to this volume—scholars of law, anthropology, sociology, political science, economics, and religious studies—disentangle diverse forms of polygamy and polyamory practiced among a range of religious and national backgrounds including Mormon and Muslim. They chart the harms and benefits these models have on practicing women, children, and men, whether they are members of independent families or of coherent religious groups. Contributors also address the complexities of evaluating this form of marriage and the ethical and legal issues surrounding regulation of the practice, including the pros and cons of legalization.

Plural marriage is the next frontier of North American marriage law and possibly the next civil rights battlefield. Students and scholars interested in polygamy, marriage, and family will find much of interest in The Polygamy Question.

Contributors: Kerry Abrams, Martha Bailey, Lori G. Beaman, Janet Bennion, Jonathan Cowden, Shoshana Grossbard, Melanie Heath, Debra Majeed, Rose McDermott, Sarah Song, Irene StrassbergFor more information, including a TOC and sample chapter, follow the link.

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

Life & Law Panel Recap: "Space Along the Rural-Urban Spectrum"

I’m delighted to report that the Life & Law in Rural America conference had an abundance of strong papers, and amidst a very interdisciplinary crowd there were many legal historians. We’re happy to have three of those legal historians provide us with panel recaps this week: Brooke Depenbusch, Smita Ghosh, and Jillian Jacklin will all contribute. More about the conference can be found, here.

Today, I want to provide a short recap of the panel that struck me the most, “Space Along the Rural-Urban Spectrum.” Elsa Devienne, a Princeton Mellon Fellow, acted as commentator for Alyse Bertenthal, Sean Fraga, Jessica Cooper, and Villiam Voinot-Baron. My apologies in advance for any mischaracterization of any of the panelists’ arguments.

Alyse Bertenthal, Ph.D. Candidate in Criminology, Law & Society at University of California, Irvine, started the panel with an insightful analysis of a publicity pamphlet from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Using the part-advertisement, part-travelogue, “Little Journeys into Water and Power Land,” her concise presentation pushed us to consider the rural as much of an ideology as place. Her analysis of the L.A. Department of Water and Power’s publicity campaign suggests that with regard to the Owen Valley Aqueduct, the rural as an ideology was constructed by urban public officials for the purposes of gaining support for the publicly owned utility and the building of the aqueduct in the early twentieth century. More than that, her narrative is one in which the “public good” was grounded in an urban area rather than those who lived in rural Owen County. Thus, attitudes toward the rural landscape and those who lived there were formed by the Department of Water and Power to achieve specific urban ends, despite the damaging long-term consequences for those in rural communities around the Owen Valley.

Kessler and Pozen's Life-Cycle Theory of Legal Theories

Jeremy K Kessler and David Pozen, Columbia Law School, have posted Working Themselves Impure: A Life-Cycle Theory of Legal Theories, which is forthcoming in the University of Chicago Law Review:

Prescriptive legal theories have a tendency to cannibalize themselves. As they develop into schools of thought, they become not only increasingly complicated but also increasingly compromised, by their own normative lights. Maturation breeds adulteration. The theories work themselves impure.

This Article identifies and diagnoses this evolutionary phenomenon. We develop a stylized model to explain the life cycle of certain particularly influential legal theories. We illustrate this life cycle through case studies of originalism, textualism, popular constitutionalism, and cost-benefit analysis, as well as a comparison with leading accounts of organizational and theoretical change in politics and science. And we argue that an appreciation of the life cycle requires a reorientation of legal advocacy and critique. The most significant threats posed by a new legal theory do not come from its neglect of significant first-order values -- the usual focus of criticism -- for those values are apt to be incorporated into the theory. Rather, the deeper threats lie in the second- and third-order social, political, and ideological effects that the adulterated theory’s persistence may foster, down the line.

Peabody to Lecture on Freedom in Law and Practice in the French Empire

On Thursday, April 7th, from 5-6pm, in HWC 2400 of Florida State University, Professor Sue Peabody, Washington State University, Vancouver, will deliver the

lecture "Freedom: Law & Practice in the French Empire.” It will be

drawn from Professor Peabody’s forthcoming book, Madeleine's Children: Family, Freedom, Secrets and Lies in France's Indian Ocean Colonies, 1750-1850.

The lecture, which is part of the Florida State University History Department’s Legal History Series, “is sponsored by the FSU Department of History’s Institute on Napoleon & the French Revolution and the Winthrop-King Institute for Contemporary French & Francophone Studies, with the generous support of the Weider Foundation.”

The announcement continues:

The lecture, which is part of the Florida State University History Department’s Legal History Series, “is sponsored by the FSU Department of History’s Institute on Napoleon & the French Revolution and the Winthrop-King Institute for Contemporary French & Francophone Studies, with the generous support of the Weider Foundation.”

The announcement continues:

Legal history is often a search for the development of coherent jurisprudence, but humans generally lead messy lives outside or even ignorant of the letter of the law. This is certainly the case with the authors of French slave law, who struggled to contain the agency of colonists and their descendants – free and unfree – in France’s Caribbean and Indian Ocean plantation colonies. The result, complicated by revolutionary disjuncture in the 1790s, was a hodgepodge and oftentimes contradictory set of policies regulating the privileges and rights of freedom: what they were and who could enjoy them.

Through the lens of biography, historians can turn legal history on its head. By following a particular set of people through time, we can see how they, themselves, understood slavery and freedom, as individuals and as a class. The story of Madeleine and her children, as slaves and in freedom, reveals not only how they forged lives and relationships within the system of colonial slave law, but how the planter class deployed legal instruments – contracts, testaments, and manumissions – to advance their own interests and to circumvent both the letter and the spirit of the law.

Goldstein on "The Cold War Trials of James Kutcher, 'The Legless Veteran'"

A new release from the "Landmark Law Cases and American Society" series at the University Press of Kansas: Discrediting the Red Scare: The Cold War Trials of James Kutcher, "The Legless Veteran," by Robert Justin Goldstein (Oakland University). A description from the Press:

During the Allies’ invasion of Italy in the thick of World War II, American soldier James Kutcher was hit by a German mortar shell and lost both of his legs. Back home, rehabilitated and given a job at the Veterans’ Administration, he was soon to learn that his battles were far from over. In 1948, in the throes of the post-war Red Scare, the hysteria over perceived Communist threats that marked the Cold War, the government moved to fire Kutcher because of his membership in a small, left-wing group that had once espoused revolutionary sentiments. Kutcher’s eight-year legal odyssey to clear his name and assert his First Amendment rights, described in full for the first time in this book, is at once a cautionary tale in a new period of patriotic one-upmanship, and a story of tenacious patriotism in its own right.

Credit

The son of Russian immigrants, James Kutcher came of age during the Great Depression. Robbed of his hope of attending college or finding work of any kind, he joined the Socialist Workers Party, left-wing and strongly anti-Soviet, in his hometown of Newark. When his membership in the SWP came back to haunt him at the height of the Red Scare, Kutcher took up the fight against efforts to punish people for their thoughts, ideas, speech, and associations. As a man who had fought for his country and paid a great price, had never done anything that could be construed as treasonous, held a low level clerical position utterly unconnected with national security, and was the sole support of his elderly parents, Kutcher cut an especially sympathetic figure in the drama of Cold War witch-hunts. In a series of confrontations, in what were highly publicized as the “case of the legless veteran,” the federal government tried to oust Kutcher from his menial Veterans’ Administration job, take away his World War II disability benefits, and to oust him and his family from their federally subsidized housing. Discrediting the Red Scare tells the story of his long legal struggle in the face of government persecution—that redoubled after every setback until the bitter end.A few blurbs:

“The case of James Kutcher, the “legless veteran,” is all but forgotten today, but it deserves to be a reminder of the mass hysteria that overtook the country during the Red Scare of the 1940s and 1950s. Robert Goldstein’s prodigious research and careful analysis do not hide the anger that he and we should feel about this case. It is a brilliant indictment of a country that forgot what the Bill of Rights meant, as well as the story of an “ordinary man” who showed extraordinary courage.” —Melvin I. UrofskyMore information is available here.

“The celebrated—Arthur Miller, Lillian Hellman, and J. Robert Oppenheimer—as well as ordinary librarians, teachers, and bus drivers—all suffered through the anti-communist hysteria of the Truman-McCarthy-Eisenhower years. Robert Goldstein’s well-researched and lively monograph helps to rescue two of the unsung heroes of this tragic era who stood up against the government witch-hunters: James Kutcher, the legless World War II veteran and outspoken Trotskyite, who triumphed over the loyalty machinery of the Veterans Administration, and his redoubtable lawyer, Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., who made that victory possible. ” —Michael E. Parrish

Monday, March 28, 2016

Fernandez on Henderson, "Creating Legal Worlds"

Over at JOTWELL, Angela Fernandez (University of Toronto - Law) has posted an admiring review of Creating Legal Worlds: Story and Style in a Culture of Argument (2015), by Greig Henderson (University of Toronto - English Department). Here are the first two paragraphs of the review:

Creating Legal Worlds, a new book by Greig Henderson, an English professor at the University of Toronto, is about rhetoric and the law and how story-telling is intrinsic to the law. Henderson revisits famous cases (and introduces readers to new cases) in which judges use a variety of rhetorical techniques to engage in persuasive (and, it turns out, at times, not so persuasive) story-telling.

Legal scholars will find value, especially for teaching, in Henderson’s analysis of judgment-writing as craft. However, I think the book has especial purchase power for legal historians, who can contrast Henderson’s approach to cases with the way they generally approach cases and their context. Rather than emphasizing the details of a case and its surrounding circumstances, Henderson emphasizes the technique of the judge as a writer. He explains the literary and rhetorical techniques that judges use (consciously and unconsciously) in order to paint a scene, play on a presumption or prejudice, generate empathy or reassurance that the right result has been reached with cool, clear and unemotional speech.Read on here.

Last call for ASLH proposals

Last call: Panel proposals for the October 2016 meetings of the American Society for Legal History in Toronto are due April 1. Details on the submission procedure are here.

LAPA Fellows Announced

The Program in Law and Public Affairs (LAPA) at Princeton University is pleased to announce its fellows for the 2016-2017 academic year:

The Program in Law and Public Affairs (LAPA) at Princeton University is pleased to announce its fellows for the 2016-2017 academic year:Kathryn Abrams, Herma Hill Kay Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of California Berkeley

Cornelia Dayton, Professor of History at the University of Connecticut

James Fleming, The Honorable Paul J. Liacos Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Intellectual Life at the Boston University School of Law

Melynda Price, Robert E. Harding, Jr. Professor of Law and Director of African American and Africana Studies at the University of Kentucky

David Rabban, Dahr Jamail, Randall Hage Jamail & Robert Lee Jamail Regents Chair in Law at the University of Texas

Sarah Schindler, Professor of Law and Glassman Faculty Research Scholar at the University of Maine School of Law

More.

Araiza, "Was Cleburne an Accident?"

William D. Araiza (Brooklyn Law School) has posted "Was Cleburne an Accident?" 19 U. Pa. J. of Const'l Law (2016, forthcoming). Here's the abstract:

City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center is a seminal case. It marked the last time the Supreme Court performed a serious analysis of whether a group should be denominated a suspect class, and thus receive heightened judicial protection from discrimination. At the same time, its application of a heightened variant of rational basis review, and its conclusion that the challenged government action was based in “irrational prejudice,” has generated three decades of academic and judicial speculation about the conditions under which such heightened rational basis review would or should be performed. Cleburne has also served as a font of the Court’s emerging “animus” doctrine, which has been at least responsible for, among other things, the remarkable string of victories gay rights plaintiffs have won at the Court over the last two decades.Hat tip: Legal Theory Blog

And yet, important parts of this consequential case may have been accidents – that is, they may have emerged as consequences not intended by a majority of the justices. Examination of several justices’ papers reveals that the majority originally planned to decide only the suspect class question, and to remand the case to the lower court for application of rational basis review. It was only late in their deliberations – and late in the 1984-85 term – when Justice White, the author of Cleburne, was prevailed upon to add the final substantive section of what became the majority opinion, which performed the rational basis review it had called for, and struck down the government’s action on that basis.

Those papers also reveal a late-erupting dispute between Justices White and Powell over whether that rational basis analysis ought to have resulted in a decision striking down the Cleburne ordinances on their face, or merely as applied to the plaintiffs’ particular group home. The resolution of that dispute ostensibly in favor of the latter approach helped create the more stringent, record-based, tone of the majority opinion’s rational basis analysis. Thus, the as-applied nature of the decision – a decision Justice White defended as allowing municipalities more leeway to regulate – helped color the opinion’s tone in a way that has since been interpreted as imposing stricter judicial review.

This Article examines the publicly-available justices’ papers to recount their deliberations in Cleburne and to consider what those deliberations tell us, not just about the case, and not just about equal protection, but about constitutional law doctrine and legal doctrine more generally. In addition to revealing and investigating the “accidents” described above, the Article also explains how the phenomena described here can have important impacts on the path of legal doctrine. This is especially true when the text – the opinion – tells a superficially logical but misleading story, as Cleburne does. For these reasons, it is both revealing and important to revisit the scene of Cleburne’s accidents.

Sunday, March 27, 2016

A Message from the ASLH Program Committee

[The following as from an email sent this evening to members of the American Society for Legal History.]

Please let us know if you have any questions or if you experience any glitches during the submission process. And thank you in advance for your patience with this transition.

As you will have seen on the ASLH website, we have put in place an on-line submission system for panel proposals for the 2016 Annual

Meeting in Toronto, and extended the deadline for proposals to April 1. The new system can be accessed here:

If you submitted your proposal early via email, please remember to resubmit using the new system.

Please let us know if you have any questions or if you experience any glitches during the submission process. And thank you in advance for your patience with this transition.

Best regards,

Victor Uribe (uribev@fiu.edu)

Bethany Berger (bethany.berger@uconn.edu)

Program Committee Co-chairs

Saturday, March 26, 2016

Weekend Roundup

- From In Custodia Legis: "Becoming the Plutarch of Renaissance Lawyers"

- From Rachel Hermann over at The Junto: "Evolution of an Article" (or, as she later puts it, a "thrilling romp through the wild and tangled forests of peer review"). Lots of good tips for junior scholars, including "A dissertation chapter is not a book chapter! And a book chapter is not an article!" and, my favorite, "This. Sh-t. Takes. Time." [KMT (alteration mine)]

- Via the Legal Scholarship Blog, word that former guest blogger Sophia Lee (University of Pennsylvania) presented a paper titled "Barnette and the First Amendment Right to Privacy" to the University of Texas faculty workshop.

- At a town hall meeting on Tuesday, April 5, at 2 p.m. in the University at Buffalo Law School, New Yorkers turn to the constitutional historian Peter J. Galie, professor emeritus in political science at Canisius College, among others, for insight into the November 2017 referendum on whether to convene a constitutional convention.

- On courtroom artists in Indiana and the Library of Congress, via the Indiana Lawyer and the New York Times.

- ICYMI: HNN's roundup on the Supreme Court confirmation fight and the Onion's savage satire, from somewhere beyond the realm of good taste.

Friday, March 25, 2016

Call for Nominations: Harold Berman Prize for Excellence in Law & Religion Scholarship

Via H-Law, we have the following call for nominations:

Harold Berman Prize for Excellence in Law & Religion Scholarship

Harold J. Berman (credit)

Starting this year, the AALS Section on Law & Religion will award the "Harold Berman Prize" to recognize scholarly excellence by an untenured professor at an AALS Member School.

The Prize will be given to the author of an article, published between July 15, 2015 and July 15, 2016, which has made an outstanding scholarly contribution to the field of law and religion.

The recipient must be a tenure-track faculty member at an AALS Member School and must have served no more than 6 years as a faculty member as of the date of the awarding of the Prize. The Prize will be awarded at the 2017 AALS Annual Meeting, scheduled for January 4-7, 2017.

Nominations should be sent by email to Professor Michael Helfand (michael.helfand@pepperdine.edu) and must be received by 5pm PST on August 15th, 2016. Nominations should include the full name, title and contact information for the nominated scholar, in addition to a PDF version of the published version of the article to be considered for the Prize. There is a limit of three nominations per nominator. Self-nominations are welcomed.

Questions about the Prize should be addressed to Professor Richard Albert (richard.albert@bc.edu), Chair of the Section on Law & Religion.

Prize Committee

Zak Calo (Hamad Bin Khalifa / Valparaiso)

Rick Garnett (Notre Dame)

Michael Helfand (Pepperdine)

Lisa Roy Shaw (Mississippi)

Our 2007 post on Harold Berman's passing is here.Contact Info:Nominations: Professor Michael Helfand, Pepperdine (michael.helfand@pepperdine.edu)

Questions about the prize: Professor Richard Albert, Boston College (richard.albert@bc.edu)Contact Email: michael.helfand@pepperdine.edu

Call for Applications: R. Roy McMurtry Fellowship in Canadian Legal History

From our friends at the Canadian Legal History Blog, a Call for Applications:

R. Roy McMurtry Fellowship in Canadian Legal History

The R. Roy McMurtry Fellowship in Canadian Legal History was created on the occasion of the retirement as Chief Justice of Ontario of the Hon. R. Roy McMurtry. It honours the contribution to Canadian legal history of Roy McMurtry, Attorney-General and Chief Justice of Ontario, founder of the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History and for many years (and currently) the Society’s President. The fellowship was established by Chief Justice McMurtry’s friends and colleagues, and endowed by private donations and the Law Foundation of Ontario.

The fellowship is to support graduate (preferably doctoral) students or those with a recently completed doctorate, to conduct research in Canadian legal history, for one year. Scholars working on any topic in the field of Canadian legal history are eligible. Applicants should be in a graduate programme at an Ontario University or, if they have a completed doctorate, be affiliated with an Ontario University. The fellowship may be held concurrently with other awards for graduate study. Eligibility is not limited to history and law programmes; persons in cognate disciplines such as criminology or political science may apply, provided the subject of the research they will conduct as a McMurtry fellow in Canadian legal history. The selection committee may take financial need into consideration.

The fellowship will be awarded in June 2016, and will have a value of $16,000. Applications will be assessed by a committee appointed by the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History and consisting of Society Directors and academics. Those interested should apply by sending:

A full curriculum vitaeA statement of the research, not exceeding 1,000 words, that they would conduct as a McMurtry fellow. The statement should clearly convey the nature of the project, the research to be carried out, and the relationship, if any, between the project and previous work done by the applicant. The names and addresses (including email addresses) of two academic referees. Please do not ask your referees to write; the Society will contact them if necessary.

For persons not currently connected with an Ontario University, an indication of how and when they intend to obtain such a connection.Please send applications to Marilyn Macfarlane, McMurtry Fellowship Selection Committee, Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, Osgoode Hall, 130 Queen Street West, Toronto, M5H 2N6, or by email to mmacfarl@lsuc.on.ca. The deadline for applications is April 30, 2016.

CLH 3:2: Lay Participation in Modern Law

A big hat tip to the ESCLH Blog for its post of the contents of Comparative Legal History 3:2, which we somehow overlooked when it appeared. The issue includes the papers from the symposium on lay participation in modern law.

A big hat tip to the ESCLH Blog for its post of the contents of Comparative Legal History 3:2, which we somehow overlooked when it appeared. The issue includes the papers from the symposium on lay participation in modern law.Introduction: Lay Participation in Modern Law: A Comparative Historical Analysis, by Markus Dubber & Heikki Pihlajamäki

Knowing the law and deciding justice: lay expertise in the democratic Athenian courts, by David Mirhady

In the rhetorically charged law courts in which ancient Athenian lay judges exercised their knowledge of the laws and so decided questions of justice, particularly where the quaestio iuris was most at issue, they exercised some quite sophisticated thinking. The judges abided by their oath to vote ‘according to the laws’, but did so with a comprehensive understanding both of the multiplicity of laws that might apply to particular cases and of the even greater number of legal principles implicit in them. After sketching the democratic aspects of Athens’ legal system, the paper begins with Plato’s Apology of Socrates before going on to detail legal reasoning advanced in Lysias’ On the Murder of Eratosthenes and Hyperides’ Against Athenogenes.Lay participation: the paradox of the jury, by Anthony Musson

Lay participation in the form of the jury has been integral to the administration of justice in England at all levels and in both civil and criminal arenas since the Middle Ages and is popularly regarded as a legacy of Magna Carta by dint of the constitutional significance attributed to the Great Charter over the centuries. Arguably juries provide a bastion against the potential harshness of the state and a buffer against arbitrariness on the part of the judge as well as injecting an element of amateurism to combat the increased professionalism of the legal system. Yet, for all the perceived benefits, serious inadequacies in jurors and even in the apparent fairness of the system have been exposed. Jury decisions, too, have come under scrutiny. This paper examines the paradox of the jury in criminal trials and compares their role in the modern legal system with the historical past.The politics of jury trials in nineteenth-century Ireland, by Niamh Howlin

This article considers aspects of lay participation in the Irish justice system, focusing on some political dimensions of the trial jury in the nineteenth century. It then identifies some broad themes common to systems of lay participation generally, and particularly nineteenth-century European systems. These include perceptions of legitimacy, state involvement and interference with jury trials, and issues around representativeness. The traditional lack of scholarship in the area of comparative criminal justice history has meant that many of the commonalities between different jury systems have been hitherto unexplored. It is hoped that this paper will contribute to a wider discussion of the various commonalities and differences in the development of lay participation in justice systems.Forensic oratory and the jury trial in nineteenth-century America, by Simon Stern

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the American jury trial was a form of popular amusement, rivalling the theatre and often likened to it. The jury's ability to find law, as well as facts, was widely if inconsistently defended. These features were consistent with a view of forensic oratory that emphasized histrionics, declamation and emotionally charged rhetoric as means of legal persuasion. By the end of the century, judges had gained more control of the law-finding power and various questions of fact had been transformed into questions of law. Many of the details that would have aided the lawyers’ dramatic efforts were screened out by a host of new exclusionary rules. These changes in forensic style may have helped to facilitate the decline of the trial, by reorienting its function away from a broadly representative one and towards one that emphasized dispassionate analysis in the service of objectivity.The schizophrenic jury and other palladia of liberty: a critical historical analysis, by Markus D. Dubber

The historiography of the jury is interestingly schizophrenic, even paradoxical. On one side is the once traditional, and still popular, history of the jury as palladium of liberty. On the other side is the once revisionist, but now widely accepted, account of the jury's origin as instrument of oppression. On one side is the jury as English, local, indigenous, democratic; on the other is the jury as French, central, foreign, autocratic. This paper reflects on this apparent paradox, regarding it as neither sui generis nor in need of resolution. Instead, from the longue durée comparative-historical perspective of New Historical Jurisprudence, the schizophrenic history of the jury and of other palladia of liberty, notably habeas corpus, can be seen to reflect the fundamental and long-standing tension between two modes of governance, law and police, rooted in the distinction between autonomy and heteronomy that has shaped the Western legal-political project since classical Athens.Book reviews:

Thursday, March 24, 2016

Weinberg on Proof of Identity and Racial Policing in US History

Jonathan Weinberg, Wayne State University Law School, has posted Proving Identity:

United States law, over the past two hundred years or so, has subjected people whose race rendered them noncitizens or of dubious citizenship to a variety of rules requiring that they carry identification documents at all times. Such laws fill a gap in the policing authority of the state, by connecting the individual’s physical body with the information the government has on file about him; they also entail humiliation and some degree of subordination. Accordingly, it’s not surprising that we’ve almost always imposed such requirements on people outside our circle of citizenship -- African-Americans in the antebellum South, Chinese immigrants, legally resident aliens. Today, though, there’s reason to think that we’re moving closer to a universal identity-papers regime.

Harriet Bolling’s Certificate of Freedom (1851) (LC)

Pfander on Standing and the Actio Popularis

James E. Pfander, Northwestern University School of Law, has posted Standing to Sue: Lessons from Scotland’s Actio Popularis:

Much of what we think we know about the judicial power in the early Republic comes from the history of English common law. Our focus on the common law seems natural enough: Blackstone’s commentaries on the laws of England shaped many an antebellum lawyer’s notion of legal practice and jurists in the twentieth century quite deliberately pointed to the courts at Westminster in discussing the origins of judicial power in America.H/t: Legal Theory Blog

An emerging body of scholarship has come to question this single-minded focus. Litigation in eighteenth century America was an eclectic affair, also drawing on the practices of the courts of equity and admiralty, which relied on Romano-canonical alternatives to the common law writ system. Recognizing an inquisitorial role for judges and often relaxing strict adversary requirements in the issuance of investitive decrees, these courts registered legal claims and tested the boundaries of official authority.

This Article examines the rules of standing to sue that emerged from one important court’s reliance on civil law modes of practice. The Scottish Court of Session heard cases both in law and equity and early developed a declaratory practice that allowed litigants to test their rights in a setting where no coercive judgment was contemplated. While the Scots imposed standing limits in private litigation – or what the courts referred to as title and interest to sue – they also permitted individuals to bring an actio popularis, or popular action, in certain circumstances. The Scottish actio popularis allowed individual suitors to press a legal claim held in common with other members of the public. By offering an account of Scots practice, this paper illuminates a remarkably mature but long ignored body of standing law, draws upon Scottish ideas to interrogate the rules of standing in the United States, and extends the growing literature on influential alternatives to the common law.

Hale on the Triumph and Decline of the Jury in America

The University Press of Kansas has released The Jury in America: Triumph and Decline (Feb. 2016), by Dennis Hale (Boston College). A description from the Press:

The jury trial is one of the formative elements of American government, vitally important even when Americans were still colonial subjects of Great Britain. When the founding generation enshrined the jury in the Constitution and Bill of Rights, they were not inventing something new, but protecting something old: one of the traditional and essential rights of all free men. Judgment by an “impartial jury” would henceforth put citizen panels at the very heart of the American legal order. And yet at the dawn of the 21st century, juries resolve just two percent of the nations legal cases and critics warn that the jury is “vanishing” from both the criminal and civil courts. The jurys critics point to sensational jury trials like those in the O. J. Simpson and Menendez cases, and conclude that the disappearance of the jury is no great loss. The jury’s defenders, from journeyman trial lawyers to members of the Supreme Court, take a different view, warning that the disappearance of the jury trial would be a profound loss.

In The Jury in America, a work that deftly combines legal history, political analysis, and storytelling, Dennis Hale takes us to the very heart of this debate to show us what the American jury system was, what it has become, and what the changes in the jury system tell us about our common political and civic life. Because the jury is so old, continuously present in the life of the American republic, it can act as a mirror, reflecting the changes going on around it. And yet because the jury is embedded in the Constitution, it has held on to its original shape more stubbornly than almost any other element in the American regime. Looking back to juries at the time of America’s founding, and forward to the fraught and diminished juries of our day, Hale traces a transformation in our understanding of ideas about sedition, race relations, negligence, expertise, the responsibilities of citizenship, and what it means to be a citizen who is “good and true” and therefore suited to the difficult tasks of judgment.

Criminal and civil trials and the jury decisions that result from them involve the most fundamental questions of right, and so go to the core of what makes the nation what it is. In this light, in conclusion, Hale considers four controversial modern trials for what they can tell us about what a jury is, and about the fate of republican government in America today.A blurb:

“Dennis Hale brings the broad vision of a gifted political theorist to assess the significance of the jury in American life, both its past centrality and its more recent marginalization. This important book provides an acute, detailed, and balanced judgment on all the central issues.” —Robert P. BurnsIt looks like Project Muse subscribers may access full content, here.

Wednesday, March 23, 2016

Zacharias on Brandeis and Judicial Review

Lawrence S. Zacharias, University of Massachusetts Amherst, has posted Reframing the Constitution: Brandeis, “Facts,” and the Nation's Deliberative Process, which appeared in the Journal Jurisprudence 20 (2013) 327-72:

During his first years on the Court, Louis Brandeis self-consciously used his opinions to reframe the Constitution and thereby refocus his colleagues' perspective on judicial review. This article elaborates on his tactical use of opening sentences to frame the Constitution's deliberative processes in their factual settings.

The reputation of Justice Louis Brandeis rests in significant part on revitalizing American legal positivism through his factual inquiry. Ironically, "Brandeis's facts," in particular their persuasive power, are still widely misunderstood. The commonplace is that Brandeis won judicial restraint simply by mustering an imposing array of facts to support rules, in particular social legislation, threatened by the Court's disapproval. Yet, as I argue here, Brandeis was more concerned with moving the Court away from a role in which it sought to replicate or second-guess the factual inquiries underlying legislative deliberations. To do so he had to divert his fellow justices' attention from "legislative facts" by using another set of facts that refocused their attention on constitutional processes. For the Constitution's structure implies requirements for the integrity and complementarity of the various deliberative processes - federal as well as state, local and administrative as well as legislative. So as the nation moved through industrialization and the nationalization of commerce, Brandeis used facts characterizing the transition to help appraise the quality of deliberation underlying the nation's laws. As I will show, these facts often appeared in the opening sentences of his opinions for the Court.

Conklin on the Political Theory of Justice Holmes

This is an old one, but, hey, it's on Holmes: William Conklin, University of Windsor, has posted The Political Theory of Mr. Justice Holmes, which appeared in Chitty’s Law Journal 26 (1978): 800-11:

Commentators of the judicial decisions of Justice Holmes have often situated the decisions inside the doctrines of freedom of expression and the rules and tests approach to legal analysis. This Paper situates his judgments in the context of a political theory. Drawing from his articles, lectures and correspondence, the Paper highlights Holmes’ reaction to the idealism and rationalism of the intellectual current before him. His view of human nature, conditioned by his war experience, is elaborated. The Paper especially examines his theory of political struggle with the process-oriented view that the dominant social groups invariably become the political elite. The Paper then connects his theory of human nature to his legal doctrines, the role of the judiciary, the nature of the state, and a legal right.H/t: Legal Theory Blog

Comparative Administrative Law at YLS

I’m pleased to be able to chair a panel at the 2016 Conference on Comparative Administrative Law, supported by the Oscar M. Ruebhausen Fund at Yale Law School and UConn Law School, and convened at the Yale Law School on April 29-30.

Administrative Law is becoming a lively field for comparative research, and the Comparative Administrative Law Initiative at Yale Law School is partly responsible for that development. In the interest of contributing to the growth of the field, the Oscar M. Ruebhausen Fund at Yale Law School and the University of Connecticut Law School will host a conference on April 29-30, 2016 for the second edition of Comparative Administrative Law, edited by Susan Rose-Ackerman and Peter Lindseth. The new edition will include many new chapters by emerging scholars and will give broader regional coverage than the first edition. Most of the contributors to the previous edition have either revised their chapters in light of current developments or asked that their chapters be reprinted. The website includes the program for the conference and a list of participants. As draft chapters arrive, they will be posted on the website with links on the conference program. Anyone interested in attending the conference should contact Cathy Orcutt.The whole schedule is here. The papers in my panel, entitled "Historical Perspectives," are

Révolution, Rechtsstaat and the Rule of Law: Historical Reflections on the Emergence of Administrative Law in Europe

Bernardo Sordi

Public Trust, Public Property, and Administrative Law: France, the UK and the US in Historical Perspective

Thomas Perroud

The Historical Impact of Administrative Law Models: Italy between the French and Anglo-American Traditions

Marco D’Alberti

Tuesday, March 22, 2016

Essays on South Carolina's First Female Supreme Court Justice

Madam Chief Justice: Jean Hoefer Toal of South Carolina, edited by W. Lewis Burke Jr. and Joan P. Assey, is out from University of South Carolina Press:

In Madam Chief Justice, editors W. Lewis Burke Jr. and Joan P. Assey chronicle the remarkable career of Jean Hoefer Toal, South Carolina's first female Supreme Court Chief Justice. As a lawyer, legislator, and judge, Toal is one of the most accomplished women in South Carolina history. In this volume, contributors, including a former and current U. S. Supreme Court justice, federal and state judges, state leaders, historians, legal scholars, leading attorneys, family, and friends, provide analysis, perspective, and biographical information about the life and career of this dynamic leader and her role in shaping South Carolina.

Growing up in Columbia during the 1950s and 60s, Jean Hoefer was a youthful witness to the civil rights movement in the state and nation. Observing the state's premier civil rights lawyer Matthew J. Perry Jr. in court encouraged her to attend law school, where she met her husband, Bill Toal. When she was admitted to the South Carolina Bar in 1968, fewer than one hundred women had been admitted in the state's history. From then forward she has been both a leader and a role model. As a lawyer she excelled in trial and appellate work and won major victories on behalf of Native Americans and women. In 1975 Toal was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives and despite her age and gender quickly became one of the most respected members of that body. During her fourteen years as a House member, Toal promoted major legislation on issues including constitutional law, criminal law, utilities regulation, local government, state appropriations, workers compensation, and freedom of information.

In 1988 Toal was sworn in as the first female justice on the Supreme Court of South Carolina, where she made her mark through her preparation and insight. She was elected chief justice in 2000, becoming the first woman ever to hold the highest position in the state's judiciary. As chief justice, Toal not only modernized her court, but also the state's judicial system. As Toal's two daughters write, the traits their mother brings to her professional life—exuberance, determination, and loyalty—are the same traits she demonstrates in her personal and family life. As a child Toal loved roller skating in the lobby of the post office, a historic building that now serves as the Supreme Court of South Carolina. From a child in Columbia to madam chief justice, she has come full circle.

Madam Chief Justice features a foreword by Sandra Day O'Connor, retired associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, and an introduction by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Devins & Klein on the Decline of Common-Law Judging

Neal Devins, William & Mary Law School, and David Klein, University of Virginia, have posted The Vanishing Common Law Judge? which is forthcoming in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review:

The common-law style of judging appears to be on its way out. Trial courts rarely shape legal policymaking by asserting decisional autonomy through distinguishing, limiting, or criticizing higher court precedent. In an earlier study, we demonstrated the reluctance of lower court judges to assert decisional autonomy by invoking the holding-dicta dichotomy. In this essay, we make use of original empirical research to study the level of deference U.S. District Judges exhibit toward higher courts and whether the level of deference has changed over time. Through an analysis of citation behavior over an 80-year period, we document a dramatic shift in judges’ practices. In the first fifty years of our study, district judges were not notably deferential to either their federal court of appeals or the U.S. Supreme Court and they regularly assessed the relevance and scope of precedents from those courts and asserted their prerogative to disregard many of them. Since then, judges have become far more likely to treat a given higher court precedent as authoritative. In so doing, lower courts have embraced a hierarchical view of judicial authority at odds with the common-law style of judging. The causes of this shift are multifold and likely permanent; we discuss several of them, including dramatic changes in legal research, the proliferation of law clerks throughout the legal system, the growing docket of lower court judges, the Supreme Court’s increasing embrace of judicial hierarchy, and the growth of the administrative state.H/t: Legal Theory Blog

The Second Hoover Commission: Lessons for Regulatory Reform

[We're moving this up, because the proceedings for this event, "on the Second Hoover Commission and the historical trajectory of regulatory reform," have now been posted on YouTube.]

The Second Hoover Commission's 60th Anniversary: Lessons for Regulatory Reform

On March 16, the ABA Section of Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice and the Hoover Institution will co-host an afternoon-long conference on the past, present, and future of regulatory reform.

Last year marked the 60th anniversary of the Second Hoover Commission's final report, "Legal Services and Procedure," proposing reforms to agency procedure, including several proposals still germane today. In honor of that report and its potential lessons for today, the Section and Hoover will present a variety of speakers looking at some historic proposals for regulatory reform, the present state of affairs, and the current prospects for reform. [RSVP here.]

2:00pm - 3:15pm: Panel 1- The Second Hoover Commission's Report on Legal Services and Procedure

David Davenport (Hoover Institution)

Joanna Grisinger (Northwestern University-Legal Studies Program)

Paul Verkuil (former chairman, ACUS)

Moderator — Nicholas Parrillo (Yale Law School; Chairman, Section’s Committee on Legal History)

3:15pm - 3:45pm: A Regulator's Perspective

FTC Commissioner Maureen Ohlhausen

4:00pm - 5:30pm: Panel 2 - Current Debates on Regulatory Reform

Maryam Brown (U.S. House of Representatives, Assistant to the Speaker for Policy)

Christopher DeMuth (Hudson Institute)

Robert Glicksman (George Washington University Law School)

Adam White (Hoover Institution; Co-Chairman, Section’s Committee on Judicial Review)

Moderator — Jeffrey Rosen (Chairman, ABA Section of Administrative Law)

5:30pm - 6:30pm: Reception

Keynote Speaker — Senator Orrin Hatch

The Second Hoover Commission's 60th Anniversary: Lessons for Regulatory Reform

On March 16, the ABA Section of Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice and the Hoover Institution will co-host an afternoon-long conference on the past, present, and future of regulatory reform.

Last year marked the 60th anniversary of the Second Hoover Commission's final report, "Legal Services and Procedure," proposing reforms to agency procedure, including several proposals still germane today. In honor of that report and its potential lessons for today, the Section and Hoover will present a variety of speakers looking at some historic proposals for regulatory reform, the present state of affairs, and the current prospects for reform. [RSVP here.]

2:00pm - 3:15pm: Panel 1- The Second Hoover Commission's Report on Legal Services and Procedure

David Davenport (Hoover Institution)

Joanna Grisinger (Northwestern University-Legal Studies Program)

Paul Verkuil (former chairman, ACUS)

Moderator — Nicholas Parrillo (Yale Law School; Chairman, Section’s Committee on Legal History)

3:15pm - 3:45pm: A Regulator's Perspective

FTC Commissioner Maureen Ohlhausen

4:00pm - 5:30pm: Panel 2 - Current Debates on Regulatory Reform

Maryam Brown (U.S. House of Representatives, Assistant to the Speaker for Policy)

Christopher DeMuth (Hudson Institute)

Robert Glicksman (George Washington University Law School)

Adam White (Hoover Institution; Co-Chairman, Section’s Committee on Judicial Review)

Moderator — Jeffrey Rosen (Chairman, ABA Section of Administrative Law)

5:30pm - 6:30pm: Reception

Keynote Speaker — Senator Orrin Hatch

CAL 3:1: The New Ancient Legal History

[Critical Analysis of Law: An International & Interdisciplinary Law Review, is out with Volume 3,, Number 1, the symposium issue The New Ancient Legal History, guest edited by Clifford Ando.]

[Critical Analysis of Law: An International & Interdisciplinary Law Review, is out with Volume 3,, Number 1, the symposium issue The New Ancient Legal History, guest edited by Clifford Ando.]The New Ancient Legal History gathers essays by some of the most interesting scholars in emergent areas of study in premodern law. Ancient legal systems are now attracting sophisticated study from a rising generation of interdisciplinary scholars. Their approaches are as varied as the material under study, but they share a critical engagement with the resources of contemporary legal scholarship and due regard for the evidentiary regimes that obtain in their separate fields.

The Varieties of Ancient Legal History Today

Clifford Ando

When Law Goes off the Rails: or, Aggadah Among the iurisprudentes

Ari Z. Bryen

Means and End(ing)s: Nomos Versus Narrative in Early Rabbinic Exegesis

Natalie B. Dohrmann

Law, Empire, and the Making of Roman Estates in the Provinces During the Late Republic

Lisa Pilar Eberle

Calculating Crime and Punishment: Unofficial Law Enforcement, Quantification, and Legitimacy in Early Imperial China

Maxim Korolkov

The State of Blame: Politics, Competition, and the Courts in Democratic Athens

Susan Lape

Jewish Law and Litigation in the Secular Courts of the Late Medieval Mediterranean

Rena N. Lauer

The Servitude of the Flesh from the Twelfth to the Fourteenth Century

Marta Madero

Consent in Roman Choice of Law

William P. Sullivan

Book Forum: Anna Su, Exporting Freedom: Religious Liberty and American Power (2016)

Book Forum: Anna Su, Exporting Freedom: Religious Liberty and American Power (2016)Exceptional and Universal? Religious Freedom in American International Law

Peter G. Danchin

Religious Liberty and American Power

Saba Mahmood

America, Christianity, and Beyond

Samuel Moyn

Saving Faith

Anna Su

Romeo on "Black Freedom and the Reconstruction of Citizenship in Civil War Missouri"

New from the University of Georgia Press: Gender and the Jubilee: Black Freedom and the Reconstruction of Citizenship in Civil War Missouri, by Sharon Romeo (University of Alberta). A description from the Press:

Gender and the Jubilee is a bold reconceptualization of black freedom during the Civil War that uncovers the political and constitutional claims made by African American women. By analyzing the actions of women in the urban environment of St. Louis and the surrounding areas of rural Missouri, Romeo uncovers the confluence of military events, policy changes, and black agency that shaped the gendered paths to freedom and citizenship.

During the turbulent years of the Civil War crisis, African American women asserted their vision of freedom through a multitude of strategies. They took concerns ordinarily under the jurisdiction of civil courts, such as assault and child custody, and transformed them into military matters. African American women petitioned military police for “free papers”; testified against former owners; fled to contraband camps; and “joined the army” with their male relatives, serving as cooks, laundresses, and nurses.

Freedwomen, and even enslaved women, used military courts to lodge complaints against employers and former masters, sought legal recognition of their marriages, and claimed pensions as the widows of war veterans. Through military venues, African American women in a state where the institution of slavery remained unmolested by the Emancipation Proclamation, demonstrated a claim on citizenship rights well before they would be guaranteed through the establishment of the Fourteenth Amendment. The litigating slave women of antebellum St. Louis, and the female activists of the Civil War period, left a rich legal heritage to those who would continue the struggle for civil rights in the postbellum era.And a blurb:

This is a landmark book. Rather than simply resulting from the work of lawmakers who ratified the Fourteenth Amendment during Reconstruction, the concept of ‘citizenship’ emerged out of the innumerable actions carried out by African Americans in the slaveholding states during the Civil War. Romeo shows that in war-torn Missouri, black women petitioned Union officers for their freedom, filed lawsuits against their former owners in military courts, and claimed widows’ pensions after the deaths of their veteran husbands. By documenting black women’s activism in a state where the Emancipation Proclamation did not even apply, Romeo forces us to reexamine precisely how and why constitutional and legal change occurred during this period.” —Timothy HuebnerMore information is available here.

Monday, March 21, 2016

Free Tom Mooney! A Yale Law Exhibit

[We’re moving this post up, because we’ve learned via H-Law of an exhibit talk by exhibition co-curator Lorne Bair: “A Martyr to the Cause: The Mooney Trial, the Communist Party, and the Pleasures of Propaganda”" at noon on Thursday, March 24, in Room 129 of the Sterling Law Building, Yale Law School (127 Wall Street, New Haven, CT.]

[Via H-Law, we have word of a new exhibit at the Yale Law Library, Free Tom Mooney!]

A hundred years ago, a bomb explosion was the pretext that San Francisco authorities needed to prosecute the militant left-wing labor organizer Tom Mooney on trumped-up murder charges. Mooney’s false conviction set off a 22-year campaign for his exoneration. The Yale Law Library, with a collection of over 150 items on the Mooney case, has mounted an exhibition marking the centennial of Mooney’s arrest.

“Free Tom Mooney! The Yale Law Library’s Tom Mooney Collection” is on display through May 27. The exhibition was curated by Lorne Bair and Hélène Golay of Lorne Bair Rare Books, and Mike Widener, Rare Book Librarian at the Yale Law Library.

The campaign to free Tom Mooney created an enormous number of print and visual materials, including legal briefs, books, pamphlets, movies, flyers, stamps, poetry, and music. It enlisted the support of such figures as James Cagney, Theodore Dreiser, Upton Sinclair, and George Bernard Shaw. It made Mooney, for a brief time, one of the world’s most famous Americans. The Law Library’s collection is a rich resource for studying the Mooney case, the American Left in the interwar years, and the emergence of modern media campaigns.

The exhibition is on display February 1 - May 27, 2016, in the Rare Book Exhibition Gallery, located on Level L2 of the Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School (127 Wall Street, New Haven, CT). Images of many of the exhibit items can be viewed in the Law Library’s Flickr site.

[Via H-Law, we have word of a new exhibit at the Yale Law Library, Free Tom Mooney!]

|

| Credit: Yale Law Library Blog |

“Free Tom Mooney! The Yale Law Library’s Tom Mooney Collection” is on display through May 27. The exhibition was curated by Lorne Bair and Hélène Golay of Lorne Bair Rare Books, and Mike Widener, Rare Book Librarian at the Yale Law Library.

The campaign to free Tom Mooney created an enormous number of print and visual materials, including legal briefs, books, pamphlets, movies, flyers, stamps, poetry, and music. It enlisted the support of such figures as James Cagney, Theodore Dreiser, Upton Sinclair, and George Bernard Shaw. It made Mooney, for a brief time, one of the world’s most famous Americans. The Law Library’s collection is a rich resource for studying the Mooney case, the American Left in the interwar years, and the emergence of modern media campaigns.

The exhibition is on display February 1 - May 27, 2016, in the Rare Book Exhibition Gallery, located on Level L2 of the Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School (127 Wall Street, New Haven, CT). Images of many of the exhibit items can be viewed in the Law Library’s Flickr site.

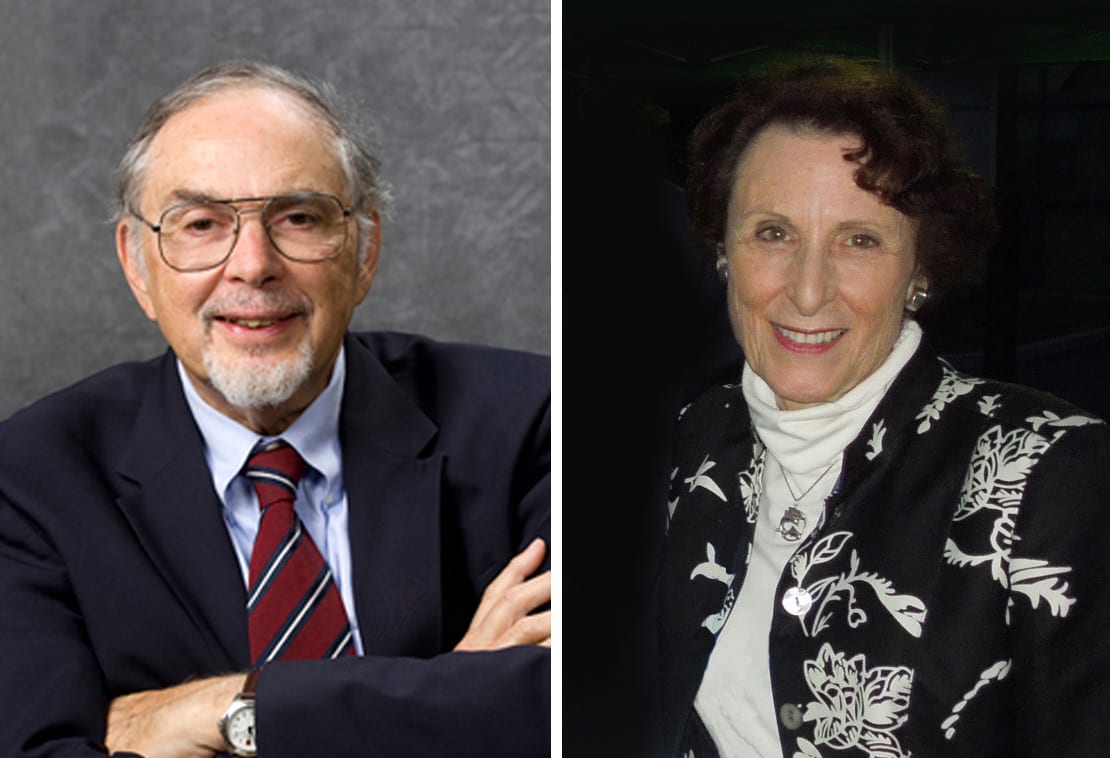

Scheiber and Scheiber on Martial Law in Hawai`i during World War II

The University of Hawai'i Press has released Bayonets in Paradise: Martial Law in Hawai`i during World War II, by Harry N. Scheiber and Jane L. Scheiber (University of California, Berkeley). A description from the Press:

Bayonets in Paradise recounts the extraordinary story of how the army imposed rigid and absolute control on the total population of Hawaii during World War II. Declared immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, martial law was all-inclusive, bringing under army rule every aspect of the Territory of Hawaiʻi's laws and governmental institutions. Even the judiciary was placed under direct subservience to the military authorities. The result was a protracted crisis in civil liberties, as the army subjected more than 400,000 civilians—citizens and alien residents alike—to sweeping, intrusive social and economic regulations and to enforcement of army orders in provost courts with no semblance of due process. In addition, the army enforced special regulations against Hawaii's large population of Japanese ancestry; thousands of Japanese Americans were investigated, hundreds were arrested, and some 2,000 were incarcerated. In marked contrast to the well-known policy of the mass removals on the West Coast, however, Hawai`i’s policy was one of “selective,” albeit preventive, detention.

Army rule in Hawai`i lasted until late 1944—making it the longest period in which an American civilian population has ever been governed under martial law. The army brass invoked the imperatives of security and “military necessity” to perpetuate its regime of censorship, curfews, forced work assignments, and arbitrary “justice” in the military courts. Broadly accepted at first, these policies led in time to dramatic clashes over the wisdom and constitutionality of martial law, involving the president, his top Cabinet officials, and the military. The authors also provide a rich analysis of the legal challenges to martial law that culminated in Duncan v. Kahanamoku, a remarkable case in which the U.S. Supreme Court finally heard argument on the martial law regime—and ruled in 1946 that provost court justice and the military’s usurpation of the civilian government had been illegal.

A sampling of the very impressive set of blurbs (other reviewers include Roger Daniels, John Witte, Jr., and Bob Gordon):Based largely on archival sources, this comprehensive, authoritative study places the long-neglected and largely unknown history of martial law in Hawaiʻi in the larger context of America's ongoing struggle between the defense of constitutional liberties and the exercise of emergency powers.

Harry and Jane Scheiber (credit)