In my teaching, I

often make a point to use—and discuss—the research I did for Black Litigants in the Antebellum American South (the cases, findings, implications, and so on). One question that

undergraduates, in particular, almost always ask me is: “what is your favorite case?”

|

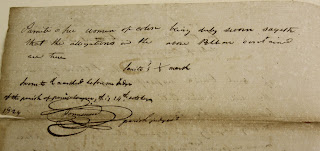

| Photo by the author |

My response varies. I have many “favorites.” Sometimes my answer involves

evidence that felt particularly hard won, such as one of the cases I found amongst

the bugs and rats in a Plaquemine, Louisiana, storage shed (research I

mentioned in a previous post). It involved a free black man who chased a white

man on horseback for miles, screaming insults and waving a loaded pistol. Sometimes

my response to the “favorites” question involves the women of the Belly family,

who took to the courts with regularity to protect and convey their property, to

enforce the terms of their contracts, and to adjudicate a number of other

disputes. They even sued their husbands. But most often my answer involves the

case that I used to open the book—the

case that I see as emblematic of the larger points about personhood and

property that I make throughout. This case involved an assault, and I will

share excerpts of my discussion of this lawsuit below.

|

| Photo by the author |

On

Sunday, September 6, 1857, two white men, William Calmes and John Buford,

violently seized, whipped, and attempted to kidnap Valerien Joseph in Pointe

Coupee Parish, Louisiana. Empowered by their duties as slave patrollers, Calmes

and Buford entered the property of another white man in search of runaway

slaves. There, they came upon Joseph, a free black carpenter engaged in his

work. Although Joseph had not given them any reason to believe he was a

runaway, and despite the protests of onlookers and Joseph’s own declarations

that he was a free man, Calmes and Buford grabbed Joseph and attempted to carry

him away. When others tried to intervene, Calmes yelled that he “would do what

he pleased,” for he intended to seize and then sell Joseph as a slave. In order

to subdue their prey, they took turns beating him in the head with a large

stick. Then Calmes removed Joseph’s clothing, forced him on his belly, and

whipped his naked body with a cowhide “forty to fifty times” while an armed

Buford stood guard to prevent others from assisting their bloodied captive. Eventually

the onlookers helped pull Joseph from the clutches of his captors, and he

managed to escape.

Five

days after the attack, Joseph sued Calmes and Buford in the Ninth Judicial

District Court, a local trial court held in Pointe Coupee Parish. He demanded

damages: the “illegal and wicked acts of said Calmes and Buford,” Joseph

insisted, “have caused your petitioner damage to the amount of fifteen hundred

dollars.” To that end, he requested that the white judge, A. D. M. Haralson,

summon his attackers to court for a public accounting of their offenses against

him, and “after due course of law,” “they be condemned” to pay him $1,500, plus

interest and court costs. The defendants denied the charges against them, and

the case went to trial. The court subpoenaed the testimony of several

witnesses, and each verified Joseph’s claims: one white man testified that

Calmes and Buford “fell upon Joseph” and “pulled him out of the yard and struck

him on the head with a stick.” Another white man (in charge of organizing slave

patrols) testified that Calmes and Buford were not in fact on patrol that day. And

still other white witnesses relayed that Joseph was “born free” of an Indian

mother and a black father. After hearing the evidence, a white jury found for

the plaintiff and issued a judgment for damages: $300 from Calmes and $200 from

Buford. The judge denied the defendants’ request for a new trial and ordered

the men to pay their debt. Both men also faced criminal charges for Joseph’s

attack, but the outcome is unknown.

|

| Photo by the author |

That

a black man would take his white attackers to court in the first place seems

paradoxical in itself. That he would win is yet more surprising. But perhaps

more interesting still is how Joseph

framed his suit.

Joseph

did not begin his petition to the court with a description of the violence

inflicted upon him (as one might in a lawsuit for damages). Instead, he framed

the case as a debt action, using the language of property and obligation. Calmes

and Buford, he insisted, owed him money: “The petition of Valerien Joseph, a

free man of color, residing in the parish, Respectfully shows,” he began, “That

William Calmes and [John] Buford, residents of the parish aforesaid, are justly

and legally indebted, in solido, unto him in the sum of fifteen hundred

dollars, with interest of 50% from judicial demand until paid.” They owed him

this amount, moreover, for their illegal assault on his property: his body.

The

jury agreed and awarded him $500 for his trouble. Buford paid the $200 shortly

after the trial, but Calmes ignored the judgment. When the amount went unpaid

over a year later, Joseph initiated additional legal proceedings against him. This

time, Judge Haralson ordered the sheriff to seize Calmes’s property, sell it at

auction, and settle his obligation to Joseph. Although Calmes absconded to

Mississippi before the court could seize his property, Joseph continued to

press his case. He made another white man, John A. Warren, a party to the

lawsuit and pursued garnishment proceedings against him. Warren possessed property belonging to Calmes, property that could be

seized and sold. When Warren failed to attend court, Joseph received a

judgment against him (in default). On April 20, 1860, mere months before

Louisiana left the Union to join a slaveholders’ republic, the court ordered

Warren to pay Joseph $350 (the original amount plus court costs and interest). When

Warren did not pay, the sheriff seized his property, sold it at auction, and

provided Joseph with the proceeds. One year later, almost to the day, shots

would be fired at Ft. Sumter initiating a war over the right to hold black

people as property.

At work in Joseph’s “demand” are a series of

interlocking understandings about the relation of one’s property to one’s

person, both in the sense of one’s physical body and in the more abstract sense

of one’s ability to be seen at law as someone who “counts” such that he or she

can make a claim. These relations between one’s person, one’s property, and

one’s legal claims form the subject of this book. To properly understand

Joseph’s suit, why he went to court, why he insisted on describing assault as a

matter of debt and obligation, why he won, and why he eventually managed to

have a white man’s property placed on the auction block, requires that we

re-evaluate our understandings of the relationship between black people,

claims-making, racial exclusion, and the legal system in the antebellum South

more broadly.

This case raises questions about who had access

to the power of the law and under what circumstances. Calmes and Buford

certainly expected that they did. After all, they were white men, men whose

race and status gave them claims to legal and political standing. They were

slave patrollers, empowered by state statute to detain possible runaways. As

slaveholders, they held property rights in black people. Thus, with the law on

their side, they might then get away with kidnapping and selling a free black

man. Their property, however, ended up on the auction block. Joseph, by

contrast, harnessed the power of the state to serve his interests and to do his

bidding: he sued two white men, bound them in obligation to him through debt,

and compelled the courts to seize white property and sell it at auction to

settle his claims and compensate him for his degradation. The court record of

the slave South is rife with stories like Joseph’s.

To encourage and recognize excellent legal scholarship and to broaden participation by new law teachers in the Annual Meeting program, the association is sponsoring a call for papers for the 33rd annual AALS Scholarly Papers Competition. Those who will have been full-time law teachers at an AALS member or fee-paid school for five years or less on July 1, 2018, are invited to submit a paper on a topic related to or concerning law. A committee of established scholars will review the submitted papers with the authors’ identities concealed.

To encourage and recognize excellent legal scholarship and to broaden participation by new law teachers in the Annual Meeting program, the association is sponsoring a call for papers for the 33rd annual AALS Scholarly Papers Competition. Those who will have been full-time law teachers at an AALS member or fee-paid school for five years or less on July 1, 2018, are invited to submit a paper on a topic related to or concerning law. A committee of established scholars will review the submitted papers with the authors’ identities concealed.