We think of James Madison as a political theorist, legislative drafter, and constitutional interpreter. Recent scholarship has fought fiercely over the nature of his political thought. Unlike other important early national leaders - John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, Edmund Randolph, James Wilson - law has been seen as largely irrelevant to Madison’s intellectual biography. Madison, however, studied law and, at least in one extant manuscript, took careful notes. These notes have been missing for over a century, and their loss contributed to the sense that Madison must not have been that interested in law. Now located, these notes reveal Madison’s significant grasp of law and his striking curiosity about the problem of language. Madison’s interest in interpretation is certainly not news to scholars. These notes, however, help to establish that this interest predated the Constitution and that his interest in constitutional interpretation was an application of a larger interest in language. Moreover, Madison thought about the problem of legal interpretation as a student of law, never from the secure status of lawyer. Over his lifetime, he advocated a variety of institutional approaches to constitutional interpretation, and this comfort with nonjudicial interpreters, along with a peculiar ambivalence about the proper location of constitutional interpretation, may owe a great deal to his self-perception as a law student but never a lawyer.

James Madison

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Bilder on James Madison as a Law Student

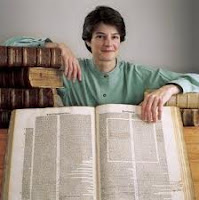

James Madison, Law Student and Demi-Lawyer by Mary Sarah Bilder, Boston College Law School, appeared in the Law and History Review, Vol. 28, pp. 389-449, May 2010. The abstract is now on SSRN, however for the publication itself, you'll need to go to the Law and History Review. Here's the abstract:

Symposium: The Legal Heritage of the Civil War

Northern Kentucky University's Chase College of Law is holding a symposium on The Legal Heritage of the Civil War, October 22, 2011.

The Civil War changed the fabric of the United States as a nation and also led to a number of landmark legal developments. These developments have had wide-reaching impacts on both national and international levels. The legal influence of the Civil War era can be seen in a number of areas of modern law, include the U.S. monetary system, the rise of federal power, military trials of terrorists, and the laws of war.

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, Chase College of Law and the Northern Kentucky Law Review will host its Fall Symposium on the Legal Heritage of the Civil War on October 22, 2011. The Symposium is an opportunity for academics, practitioners, and students to exchange ideas and explore current legal issues that originate from the Civil War era. The Northern Kentucky Law Review invites you to attend this unique Symposium as the crossroads of history and modern law are explored.

The symposium will be held in the Student Union Ballroom at Northern Kentucky University, in Highland Heights, Kentucky. Contact them here to register or for more information.

Dale, Criminal Justice in the United States, 1789-1939

Our former guest blogger Elizabeth Dale, University of Florida, has just published a smart new book Criminal Justice in the United States, 1789–1939, in the New Histories of American Law Series at Cambridge University Press.

Here's the book description:

Here's the book description:

You can find the cloth and kindle copies on Amazon, and they'll ship the paperpack later, but in the meantime you can request an examination copy from the press.

Here's the book description:

Here's the book description:This book chronicles the development of criminal law in America, from the beginning of the constitutional era (1789) through the rise of the New Deal order (1939). Elizabeth Dale discusses the changes in criminal law during that period, tracing shifts in policing, law, the courts, and punishment. She also analyzes the role that popular justice – lynch mobs, vigilance committees, law-and-order societies, and community shunning – played in the development of America's criminal justice system. This book explores the relation between changes in America's criminal justice system and its constitutional order.And the blurbs:

"This is a highly comprehensive, thoughtful, and insightful overview of the history of American criminal justice over the course of the long nineteenth century. Remarkably sensitive to larger trends and local nuance in the development of American criminal justice, Elizabeth Dale's masterful book should be read by all interested in the history of American law." – Michael J. Pfeifer, author of The Roots of Rough Justice: Origins of American Lynching

"This fine book provides both a broad synthesis and a thought-provoking interpretation of criminal justice in the United States from 1789 to 1939. Elizabeth Dale's analysis contains many moving parts: federal and state governments, courts and legislatures, judges and juries, constitutional rulings and lynch mobs, and more. The book's emphasis on the ever-changing interplay between formal law and popular notions of justice invites readers to reflect on the enduring tension between the rule of law and democracy." – John Wertheimer, Davidson College

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Swan on Gender and Erotic Triangles and Tort Law History

A New Tortious Interference with Contractual Relations: Gender and Erotic Triangles in Lumley v. Gye is a new article by Sarah Lynnda Swan, Columbia University Law School. It is forthcoming in the Harvard Journal of Law and Gender, Vol. 35, 2012. Here's the abstract:

The tort of interference with contractual relations has many puzzling features that conflict with fundamental principles of contract and tort law. This Article considers how gender influenced the structure of the tort and gave rise to many of these anomalies. Lumley v. Gye, the English case that first established interference with contractual relations, arose from a specifically gendered dispute: two men fighting over a woman. This type of male—male—female configuration creates an erotic triangle, a common archetype in Western culture. The causes of action that served as the legal precedents for interference with contractual relations – enticement, seduction, and criminal conversation – are previous instances where the law regulated gendered triangular conflicts. Enticement prohibited a rival male from taking another man’s servant, seduction prohibited a rival male from taking another man’s daughter, and criminal conversation prohibited a rival male from taking another man’s wife.

In Lumley v. Gye, the court expanded these precedents and created a cause of action that allowed Lumley to bring an action against his male rival for essentially “taking” his contracted female employee. The gendered basis for the tort explains its most problematic aspects, including why it imposes obligations on non-contractual parties, ignores the role of the breaching promisor in causing the wrong, and treats her as the property of the original promisee. In order to remedy these problematic features, the tort should be restructured as one of mixed joint liability. Further, damages should be limited to those available in contract.

Emanuel on Elbert Tuttle and Civil Rights

Anne S. Emanuel, Georgia State Law, has posted the preface to her new biography, Elbert Parr Tuttle: Chief Jurist of the Civil Rights Revolution (University of Georgia Press, 2011). Here is the abstract:

Dennis J. Hutchinson, William Rainey Harper Professor in the College and Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Chicago, says of the book:The preface to the first full biography of Elbert Tuttle, the judge who led the historic Fifth Circuit – the federal court with jurisdiction over most of the deep south – through the most tumultuous years of the Civil Rights Revolution. Tuttle had co-founded a prestigious law firm; litigated two major constitutional cases, Herndon v. Lowry (1937) and Johnson v. Zerbst (1938); earned a Purple Heart in the battle for Okinawa; and led the effort to build a viable Republican Party in Georgia – all before he joined the Fifth Circuit in 1954. When he became Chief Judge in 1960, six years had passed since Brown v. Board of Education had been decided and almost nothing had changed. Jim Crow segregation, our American apartheid, remained firmly in place. His swift, decisive rulings and his unprecedented use of the All Writs Act effectively neutralized the delaying tactics of diehard segregationalists, from school board members and voter registrars to obstructionist judges and governors, across the South.

The role of federal judges in the civil rights movement has been studied thoroughly, but Anne Emanuel has a larger story to tell about the man who served as chief judge of the largest appeals court in the South during the heyday of court-ordered racial desegregation. Elbert Tuttle, raised in Hawaii and educated in New York, led a remarkable life long before being appointed to the bench. He was active working to promote civil liberties during the 1930s, went to war in middle age and became a decorated combat veteran, and helped to secure Dwight Eisenhower’s nomination for President during the bitter 1952 Republican Convention. All the while he was a quiet, unassuming father of two and co-partner in one of the most successful law firms in the region. Emanuel knew the judge, has mined his working papers, and writes with a sure feel for this modest man who cast such a large shadow over his adopted South.And Mark Tushnet, William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law, Harvard Law School, writes:

Anne Emanuel admirably describes the career—in war, politics, and law—of a judge who was at the center of enforcing civil rights law in the 1960s. Full of interesting detail, Elbert Parr Tuttle tells us much about how one person’s life can shape the law.

Monday, August 29, 2011

University of Virginia Legal History Workshop

The University of Virginia School of Law announces the participants in our legal history workshop this academic year. Here are the presenters and the titles of their workshop papers:

Fall:

October 10: Allison Tirres, DePaul Law School

Title: “Contested Terrain: Citizenship in the Borderlands during Civil War and Reconstruction”

November 14: Ed Larson, Pepperdine Law School

Title: “The Constitutionality of Lame-Duck Lawmaking: The History, Intent, and Meaning of the Twentieth Amendment”

November 28: Cynthia Nicolletti: Mississippi College of Law

Title: "International Law and the American Civil War"

Spring:

February 13: Mitra Sharafi, University of Wisconsin Law School

Title TBA

March 12: Kara Swanson, Northeastern University Law School

Title: “Reproductive Medicine in the Legal Shadows: Artificial Insemination, 1890-1950”

April 9: Al Brophy, University of North Carolina Law School

Title: “The Jurisprudence of Slavery and Freedom at the University of Virginia – History, Natural Law, and Utility, 1831-1861”

April 23: Deborah Dinner, Washington University in St. Louis Law School

Title: “Costs of Life: Maternal Employment, Reproductive Choice, & the Debate over Pregnancy Disability Benefits”

So long, farewell

I often listen to Green Day’s Good Riddance (Time of Your Life), which begins:

Another turning point, a fork stuck in the road

Time grabs you by the wrist, directs you where to go

So make the best of this test, and don't ask why

It's not a question, but a lesson learned in time

These lines remind me of what I enjoy most about editing Law and History Review, and also why I decided to apply for the position in 2004. Although I have always been committed to my own research, after my first book went into production I was not entirely sure what to do next. I was working on a couple of articles, but did not at the time have a good idea for my next book-length project. I had run smack into a fork stuck in the road.

Journal editing, I learned from experienced colleagues, builds contingency into your everyday academic life. You never know when the next submission will arrive, who the author will be, or the topic. Opening my inbox, as I soon discovered, introduced me to people and subjects that were unfamiliar. I continuously reached the limits of my own knowledge of the field. It was (and is) a humbling experience, but also why so many of us became scholars in the first place. As it turned out, manuscripts grabbed me by the wrist and directed me where to go.

Every manuscript is a new test. I’ve already blogged about conducting the “in-house” review, but the next challenge is finding qualified reviewers for those manuscripts that I “send out” for peer review. LHR uses four reviewers per manuscript, which allows me to invite scholars with different perspectives to evaluate every submission. In some instances, I invite one reviewer to serve specifically as a generalist who can push an author to broaden his or her article to reach a larger audience. Occasionally, one or more of the reviewers who I would most like to evaluate a manuscript are unavailable for a variety of reasons. This can throw off the review process. But once you make the commitment to send a manuscript out, you don’t ask why. I also learned not to read reports as soon as they arrived. Instead, I wait until I have all the reports. The first report, which may be overly enthusiastic or negative, can color how you read subsequent ones.

As I have learned, editing a journal is like working on a book. As long as you are excited by the project, you need to continue. Once the enthusiasm is truly gone, you’ve reached another turning point. It is time to be done.

Fortunately, I still love to read new submissions. But soon enough, it will be time for someone else to have the time of their life with Law and History Review.

I truly appreciate the opportunity to have served as a guest blogger for my favorite blog, and look forward to seeing everyone at ASLH in November. Thanks for reading!

Another turning point, a fork stuck in the road

Time grabs you by the wrist, directs you where to go

So make the best of this test, and don't ask why

It's not a question, but a lesson learned in time

These lines remind me of what I enjoy most about editing Law and History Review, and also why I decided to apply for the position in 2004. Although I have always been committed to my own research, after my first book went into production I was not entirely sure what to do next. I was working on a couple of articles, but did not at the time have a good idea for my next book-length project. I had run smack into a fork stuck in the road.

Journal editing, I learned from experienced colleagues, builds contingency into your everyday academic life. You never know when the next submission will arrive, who the author will be, or the topic. Opening my inbox, as I soon discovered, introduced me to people and subjects that were unfamiliar. I continuously reached the limits of my own knowledge of the field. It was (and is) a humbling experience, but also why so many of us became scholars in the first place. As it turned out, manuscripts grabbed me by the wrist and directed me where to go.

Every manuscript is a new test. I’ve already blogged about conducting the “in-house” review, but the next challenge is finding qualified reviewers for those manuscripts that I “send out” for peer review. LHR uses four reviewers per manuscript, which allows me to invite scholars with different perspectives to evaluate every submission. In some instances, I invite one reviewer to serve specifically as a generalist who can push an author to broaden his or her article to reach a larger audience. Occasionally, one or more of the reviewers who I would most like to evaluate a manuscript are unavailable for a variety of reasons. This can throw off the review process. But once you make the commitment to send a manuscript out, you don’t ask why. I also learned not to read reports as soon as they arrived. Instead, I wait until I have all the reports. The first report, which may be overly enthusiastic or negative, can color how you read subsequent ones.

As I have learned, editing a journal is like working on a book. As long as you are excited by the project, you need to continue. Once the enthusiasm is truly gone, you’ve reached another turning point. It is time to be done.

Fortunately, I still love to read new submissions. But soon enough, it will be time for someone else to have the time of their life with Law and History Review.

I truly appreciate the opportunity to have served as a guest blogger for my favorite blog, and look forward to seeing everyone at ASLH in November. Thanks for reading!

Federal Court Records vs. The Shredder, Round 2

Earlier this month I noted the National Archives’ new retention policy on “non-trial” federal district court records created since 1970. The Associated Press reporter Michael Tarm published a story on the policy last Friday, entitled Millions of US Court Records Bound For Shredder. Here is an additional report, relating to criminal case files, which I can make thanks to some communications from Michael J. Churgin, a professor at the University of Texas Law School and chair of the Committee on Documentary Preservation of the American Society for Legal History.

The policy in question, N1-21-11-1, is being considered by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in consultation with the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. It would treat all court files in federal criminal cases created between the 1776 and 1970 as permanent records. It does the same for (1) “case files dated 1970 or later which were terminated during or after trial”; (2) “any criminal case file determined by court officials or by NARA to have historical value”; and (3) “non-trial criminal cases relating to treason and national security or to embezzlement, fraud, or bribery by a public official.” (The national security and treason offenses include alien registration, treason, espionage, sabotage, sedition, Smith Act, and exportation of war materials.)

Two classes of records are deemed temporary. First, under an earlier policy (N1-021-86-1), “misdemeanor and petty offense proceedings conducted by U.S. magistrate judges in cases not assigned a district court docket number” will be destroyed five years after closing. An appraisal conducted for NARA last May explained that the records “document minor routine offenses, such as traffic offenses on Federal property, that have no historical value.”

The second class of temporary records are non-magistrate criminal cases from 1970 on that never reached the trial stage, aren’t deemed to have historical value, and don’t relate to sedition or public corruption. According to the NARA’s appraisal, these case “are generally routine in nature and do not contain the substantive documentation that might make them useful for research.” If they cannot be donated, NARA will dispose of them 15 years after a file was closed. Trial cases, the appraisal opined, “will provide sufficient documentation of the operation of the criminal judicial system.” The largest categories of offenses in this class involve drugs (about 25 percent), immigration (about 25 percent), and property and firearms (about 30 percent).

This summer, Professor Churgin, on behalf of the ASLH’s committee, asked that NARA sample and permanently preserve files from this second class of temporary records. Churgin contrasted the proposed policy for criminal cases with that instituted for bankruptcy cases. Initially, many bankruptcy records created after 1940 were to be destroyed, but after Churgin assured NARA that “bankruptcy records certainly are not regarded as of limited interest by historians,” sampling was instituted. The precedent of the Harvard's Bankruptcy Data Project doubtless was influential. The project had already published several studies based on a random sample of 1500 to 2500 individual bankruptcies filed under Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 from ten districts for 1981, 1991, and 2001. The procedures NARA ultimately adopted will create a much larger and broader sample. For each district and every year, 2.5 percent of the “temporary” files will be preserved.

Churgin commented that “the strength of the bankruptcy schedule . . . is the use of sampling" and asked that non-trial criminal cases be sampled as well. After all, he observed, drug and immigration cases speak to “major issues of national policy." He directed NARA’s attention to California Rule of Court 10.855, which provides for the sampling of the trial and non-trial files of the state's superior courts.

Churgin also suggested that more immediate interests than those of historians and their readers were at stake. This summer the U.S. Sentencing Commission unanimously voted to give retroactive effect to a proposed amendment of the sentencing guidelines to reduce the sentences of federal crack cocaine offenders “who meet certain criteria established by the Commission and considered by the courts.” Had the NARA’s proposed policy been in place, Churgin remarked, “the case file records of countless inmates still in federal custody, who originally pled guilty, would already be destroyed.”

The policy in question, N1-21-11-1, is being considered by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in consultation with the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. It would treat all court files in federal criminal cases created between the 1776 and 1970 as permanent records. It does the same for (1) “case files dated 1970 or later which were terminated during or after trial”; (2) “any criminal case file determined by court officials or by NARA to have historical value”; and (3) “non-trial criminal cases relating to treason and national security or to embezzlement, fraud, or bribery by a public official.” (The national security and treason offenses include alien registration, treason, espionage, sabotage, sedition, Smith Act, and exportation of war materials.)

Two classes of records are deemed temporary. First, under an earlier policy (N1-021-86-1), “misdemeanor and petty offense proceedings conducted by U.S. magistrate judges in cases not assigned a district court docket number” will be destroyed five years after closing. An appraisal conducted for NARA last May explained that the records “document minor routine offenses, such as traffic offenses on Federal property, that have no historical value.”

The second class of temporary records are non-magistrate criminal cases from 1970 on that never reached the trial stage, aren’t deemed to have historical value, and don’t relate to sedition or public corruption. According to the NARA’s appraisal, these case “are generally routine in nature and do not contain the substantive documentation that might make them useful for research.” If they cannot be donated, NARA will dispose of them 15 years after a file was closed. Trial cases, the appraisal opined, “will provide sufficient documentation of the operation of the criminal judicial system.” The largest categories of offenses in this class involve drugs (about 25 percent), immigration (about 25 percent), and property and firearms (about 30 percent).

This summer, Professor Churgin, on behalf of the ASLH’s committee, asked that NARA sample and permanently preserve files from this second class of temporary records. Churgin contrasted the proposed policy for criminal cases with that instituted for bankruptcy cases. Initially, many bankruptcy records created after 1940 were to be destroyed, but after Churgin assured NARA that “bankruptcy records certainly are not regarded as of limited interest by historians,” sampling was instituted. The precedent of the Harvard's Bankruptcy Data Project doubtless was influential. The project had already published several studies based on a random sample of 1500 to 2500 individual bankruptcies filed under Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 from ten districts for 1981, 1991, and 2001. The procedures NARA ultimately adopted will create a much larger and broader sample. For each district and every year, 2.5 percent of the “temporary” files will be preserved.

Churgin commented that “the strength of the bankruptcy schedule . . . is the use of sampling" and asked that non-trial criminal cases be sampled as well. After all, he observed, drug and immigration cases speak to “major issues of national policy." He directed NARA’s attention to California Rule of Court 10.855, which provides for the sampling of the trial and non-trial files of the state's superior courts.

Churgin also suggested that more immediate interests than those of historians and their readers were at stake. This summer the U.S. Sentencing Commission unanimously voted to give retroactive effect to a proposed amendment of the sentencing guidelines to reduce the sentences of federal crack cocaine offenders “who meet certain criteria established by the Commission and considered by the courts.” Had the NARA’s proposed policy been in place, Churgin remarked, “the case file records of countless inmates still in federal custody, who originally pled guilty, would already be destroyed.”

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Tanenhaus, The Constitutional Rights of Children: In Re Gault and Juvenile Justice

Our guest blogger David Tanenhaus has a new book that is almost out: The Constitutional Rights of Children: In Re Gault and Juvenile Justice. The publication date is September 2011, so it is likely to start shipping any day. Here's the book description:

When fifteen-year-old Gerald Gault of Globe, Arizona, allegedly made an obscene phone call to a neighbor, he was arrested by the local police, who failed to inform his parents. After a hearing in which the neighbor didn't even testify, Gault was promptly sentenced to six years in a juvenile "boot camp"--for an offense that would have cost an adult only two months.Here are the blurbs:

Even in a nation fed up with juvenile delinquency, that sentence seemed over the top and inspired a spirited defense on Gault's behalf. Led by Norman Dorsen, the ACLU ultimately took Gault's case to the Supreme Court and in 1967 won a landmark decision authored by Justice Abe Fortas. Widely celebrated as the most important children's rights case of the twentieth century, In re Gault affirmed that children have some of the same rights as adults and formally incorporated the Fourteenth Amendment's due process protections into the administration of the nation's juvenile courts.

Placing this case within the context of its changing times, David Tanenhaus shows how the ACLU litigated Gault by questioning the Progressive Era assumption that juvenile courts should not follow criminal procedure. He then takes readers to the Supreme Court to fully explore the oral arguments and examine how the Court came to decide Gault, focusing on Justice Fortas's majority opinion, concurring opinions, Justice Potter Stewart's lone dissent, and initial responses to the decision.

The book explores the contested legacy of Gault, charting changes and continuity in juvenile justice within the contexts of the ascendancy of conservative constitutionalism and Americans' embrace of mass incarceration as a penal strategy. An epilogue about Redding v. Safford--a 2009 decision involving a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl, also from Arizona, who was forced to undress because she was suspected of hiding drugs in her underwear--reminds us why Gault is of lasting consequence.

Gault is a story of revolutionary constitutionalism that also reveals the tenacity of localism in American legal history. Tanenhaus's meticulous explication raises troubling questions about how local communities treat their children as it confirms the importance of the Supreme Court's decisions about the constitutional rights of minors.

This book is part of the Landmark Law Cases and American Society series, University Press of Kansas.

"A marvelous study that delivers a richly detailed, meticulously analyzed, and elegantly written exploration of the Court's seminal decision concerning the procedural rights of children. . . . An outstanding book."--Barry C. Feld, author of Bad Kids: Race and the Transformation of the Juvenile Court

"Tanenhaus brings the Gault case alive and shows how a seemingly trivial event can illuminate a very broad legal landscape."--Michael Grossberg, coeditor of the three-volume Cambridge History of Law in the United States

"A sophisticated and insightful account that tells the story of the last great battle in the due process revolution."--Franklin E. Zimring, author of American Juvenile Justice

Book Review Round-Up

Readers who work with images, either in teaching or scholarship, may be interested in Errol Morris's Believing Is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography) (Penguin), reviewed this week in both the Los Angeles Times and the Wall Street Journal (subscribers only). According to the WSJ review, it is the result of the film director's interest in the circumstances surrounding iconic photographs (Roger Fenton's famous shots from the Crimean War, Dorothea Lange's work for the Farm Security Administration, the damning images from Abu Ghraib) and, ultimately, about "what constitutes photo graphic truth."

Readers who work with images, either in teaching or scholarship, may be interested in Errol Morris's Believing Is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography) (Penguin), reviewed this week in both the Los Angeles Times and the Wall Street Journal (subscribers only). According to the WSJ review, it is the result of the film director's interest in the circumstances surrounding iconic photographs (Roger Fenton's famous shots from the Crimean War, Dorothea Lange's work for the Farm Security Administration, the damning images from Abu Ghraib) and, ultimately, about "what constitutes photo graphic truth." The WSJ (subscribers only) also reviews Leningrad: The Epic Siege of World War II, 1941-44 (Walker & Co.), by Anna Reid (here); Ethan Allen: His Life and Times (Norton), by Willard Sterne Randall (here); and The Life and Thought of Herbert Butterfield: History, Science and God (Cambridge), by Michael Bentley (here).

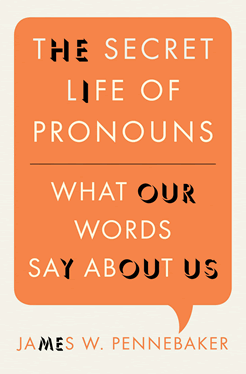

The New York Times covers The Secret Life of Pronouns: What Our Words Say About Us (Bloomsbury), by social psychologist James W. Pennebaker (here); Wendy and the Lost Boys: The Uncommon Life of Wendy Wasserstein (Penguin), by Julie Salamon (here); and Redeemers: Ideas and Power in Latin America (Harper/HarperCollins), by Enrique Krauze (here) (mentioned in an earlier round-up, here).

Readers might also enjoy Geoff Dyer's essay on "What We Do to Books." Fair warning: you might be grossed out by the part about the blood stains.

The Washington Post spotlights The Honored Dead: A Story of Friendship, Murder, and the Search for Truth in the Arab World (Spiegel & Grau), by Joseph Braude (here); The Secrets of the FBI (Crown), by Ronald Kessler (here); and Class Warfare: Inside the Fight to Fix America’s Schools (Simon & Schuster) by Steven Brill (here) (mentioned in last week's round-up, here). The Kessler review, by Bryan Burrough, is fun, if a bit snarky ("the FBI’s Quantico, Va., training ground . . . can’t be too secret if it was portrayed 20 years ago in 'Silence of the Lambs'").

The Post also spotlights three books on Libya, picked by Dirk Vandewalle (Dartmouth College). The two histories and one novel "admirably capture the evolution of Libya under its strong-arm leader."

Over at The New Republic: The Book, you'll find more discussion of a hot topic: teachers unions and their significance for the U.S. education system. Richard D. Kahlenberg reviews Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America's Public Schools (Brookings Institution), by Terry Moe. Here's a taste:

The book’s title, Special Interest, invokes a term historically applied to wealthy and powerful entities such as oil companies, tobacco interests, and gun manufacturers, whose narrow aims are often recognized as colliding with the more general public interest in such matters as clean water, good health, and public safety. Do rank and file teachers, who educate American school children and earn on average about $54,000 a year, really fall into the same category? Moe thinks so.Kahlenberg disagrees.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Saul on The Legal Response of the League of Nations to Terrorism

The Legal Response of the League of Nations to Terrorism has just been posted by Ben Saul, University of Sydney - Faculty of Law. It appeared in the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 78-102, 2006. Here's the abstract:

Terrorism was first confronted as a discrete subject matter of international law by the international community in the mid 1930s, following the assassination of a Yugoslavian king and a French foreign minister by ethnic separatists. The League’s attempt to generically define terrorism in an international treaty prefigured many of the legal, political, ideological and rhetorical disputes which came to plague the international community’s attempts to define terrorism in the fifty years after the Second World War. Although the treaty never entered into force following the dissolution of the League itself, the League’s core definition has been highly resilient and has influenced subsequent legal efforts to define terrorism. While the League’s 1937 Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of Terrorism is often referred to obliquely in international legal discussions of terrorism, the drafting of the Convention has seldom been intensively analysed. By closely examining its drafting, this article elucidates how the drafters of the Convention agreed on a definition of terrorism, and why they rejected alternative definitions. In doing so, it hopes to refresh and enliven current international debates about definition in the wake of the United Nation’s sixtieth anniversary year, which saw renewed emphasis placed on the quest for definition.

American Political Thought

[Here's an announcement of a journal that may be of interest.]

The University of Chicago Press is pleased to announce the launch of a new journal in association with the Notre Dame Program in Constitutional Studies and the Jack Miller Center, a non-profit foundation. Submissions are currently being considered for its inaugural year.

Interdisciplinary in scope, American Political Thought: A Journal of Ideas, Institutions, and Culture bridges the gap between historical, empirical, and theoretical, and is the only journal dedicated exclusively to the study of American political thought. APT will feature research by political scientists, historians, literary scholars, economists, and philosophers who study the texts, authors, and ideas at the foundation of the American political tradition.

Scholars from all related disciplines are encouraged to submit papers. The editors are seeking papers that will explore key political concepts such as democracy, constitutionalism, equality, liberty, citizenship, political identity, the role of the state, and classic thinkers in the American tradition.

Developed in response to renewed vitality in the field, APT will publish research articles, review essays, and book reviews. Each issue will contain approximately five articles (with a flexible length requirement), an essay book review, and eight to ten shorter reviews

The University of Chicago Press is pleased to announce the launch of a new journal in association with the Notre Dame Program in Constitutional Studies and the Jack Miller Center, a non-profit foundation. Submissions are currently being considered for its inaugural year.

Interdisciplinary in scope, American Political Thought: A Journal of Ideas, Institutions, and Culture bridges the gap between historical, empirical, and theoretical, and is the only journal dedicated exclusively to the study of American political thought. APT will feature research by political scientists, historians, literary scholars, economists, and philosophers who study the texts, authors, and ideas at the foundation of the American political tradition.

Scholars from all related disciplines are encouraged to submit papers. The editors are seeking papers that will explore key political concepts such as democracy, constitutionalism, equality, liberty, citizenship, political identity, the role of the state, and classic thinkers in the American tradition.

Developed in response to renewed vitality in the field, APT will publish research articles, review essays, and book reviews. Each issue will contain approximately five articles (with a flexible length requirement), an essay book review, and eight to ten shorter reviews

Friday, August 26, 2011

Kluge Fellows Announced

The Library of Congress has announced this year's Kluge Center Fellows. Among them is Emily Kadens, Texas Law (and currently visiting at Georgetown Law). Her topic is "Theories of Custom as Law in the Writings of Medieval and Early Modern Civilian Jurists."

Warren Center Fellowships on Everyday Life

The theme for next year's Warren Center at Harvard is: Everyday Life: The Textures and Politics of the Ordinary, Persistent, and Repeated. Here's the call for applications:

Harvard's Charles Warren Center invites applications from scholars of U.S. cultural history, social history, performance studies, historical sociology and anthropology, and related fields to explore everyday life in the United States. This seminar seeks to develop new ways to connect the closely-observed textures of small-scale experiences to broad political concerns. How might we understand the expansive stakes in ordinary, persistent, and repeated activities? To explore this question, we seek scholars from diverse disciplines and interdisciplines who will bring to the conversation distinct analytical tools by which to examine everyday life. Scholars of any period or region of the U.S., or the U.S in transnational context, are welcome. Topics of study may include everyday activities such as work, sex, public/civic engagement, consumption, schooling, religion, parenting, and the management of sickness and health; material culture (including clothing, food, books, vernacular architecture, land, computers, etc.); affect and emotions; and texts or performances that function through repetition or replication (theatre, periodical literature, photography, advertising, film, radio, television, MP3s, YouTube, etc.). Scholars who explore the connections between everyday life and the construction and maintenance of race, gender, sexuality, class, and other categories of analysis are especially welcome. Seminar participants will unite across diverse disciplines and topics through a shared commitment to analyzing the politics of ordinary rituals and behaviors.The theme for 2013-14 is: The Environment and the American Past: Hot Topic?

Fellows will present their work in a seminar led by Robin Bernstein (African and African American Studies and Studies in Women, Gender, and Sexuality) and Lizabeth Cohen (History). Applicants may not be degree candidates and should have a Ph.D. or equivalent. We especially seek applicants who embrace the challenges of forging scholarly conversations across disciplines. Fellows have library privileges and an office which they must use for at least the 9-mo. academic year. Stipends: individually determined according to fellow needs and Center resources. Application (from our website) due January 15, 2012; decisions in early March. Emerson Hall 400, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138

Phone: 617.495.3591

Fax: 617.496.2111

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)