This Article explores the religious origins of the right to alter or abolish government. I show in Part I that the right was widely accepted among the American colonies as expressed through their constitutions and, later, the federal constitution. In Part II, I usher the reader back in time and across the continent to seventeenth century England. There, I introduce two men who would have abhorred everything about American constitutional democracy - King James I and the philosopher Sir Robert Filmer. Both men, prominent in their respective domains of authority, devoted themselves to the governing axiom that kings were bequeathed a right by God to absolute rule. Part III sketches the seventeenth century arguments of two other Englishmen, also prominent--the philosophers John Locke and Algernon Sidney - who challenged James and Filmer. Locke and Sidney argued that God had never sanctioned the divine right of kings and instead had justified the people’s right to overthrow tyrants.

The arguments of Locke and Sidney will, as I show in subsequent sections, influence the American clergy who supported war against Britain and the right of revolution in general. Indeed, the development of this connection will occupy me for the remainder of the Article, but, in Part IV, I take a brief respite to summarize the historical circumstances that severely hampered governmental control over religion in colonial America and thus provided partially autonomous spaces for people to reflect on religion, including in ways that would inform their right to alter or abolish government. I illustrate in Part V how several prominent American clergymen, following Locke and Sidney, rejected as impossible the divine and supposedly infallible status of rulers. God, the clergy insisted, was the only one who could claim such infallibility; the clergy warned that rulers would do well to devote themselves to the people’s well being, not the former’s aggrandizement. In Part VI, I argue that, again echoing Locke and Sidney, a prominent group of American clergymen insisted that, contrary to the anti-democratic jeers of monarchists, God had given people the capacity for reason which enabled them to make meaningful decisions about their political future. I conclude in Part VII by illustrating how the federal and state constitutions following the American Revolution sought to protect conditions for the faithful to contemplate the religious meaning of the right to alter or abolish government.

Monday, November 30, 2009

Kang on The Religious Origins of the Constitutional Right of Revolution

Sunday, November 29, 2009

Sunday book review round-up

AMERICAN ORIGINAL: The Life and Constitution of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia by Joan Biskupic is reviewed in the Washington Post.

AMERICAN ORIGINAL: The Life and Constitution of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia by Joan Biskupic is reviewed in the Washington Post.Dominic Sandbrook, "History Books of the Year," Telegraph, 26 November, takes a crack at naming the best of a year's books in history. See also: "100 Notable Books of 2009: Non-fiction," NYT, 6 December; and Benjamin Schwarz, "Books of the Year," Atlantic, December.

Irish Legal History: Two New Essays

Thanks to Robert Richards for bringing to our attention the publication last September by the University College Dublin Press of People, Politics and Power: Essays on Irish History 1660-1850 in Honour of James I. McGuire, edited by James Kelly, John McCafferty, Charles Ivar McGrath, because we would otherwise have missed its two chapters on legal history: Hazel Maynard's "The Irish Legal Profession and the Catholic Revival, 1660-1689," and John Bergin's "Irish Private Divorce Bills and Acts of the Eighteenth Century."

Thanks to Robert Richards for bringing to our attention the publication last September by the University College Dublin Press of People, Politics and Power: Essays on Irish History 1660-1850 in Honour of James I. McGuire, edited by James Kelly, John McCafferty, Charles Ivar McGrath, because we would otherwise have missed its two chapters on legal history: Hazel Maynard's "The Irish Legal Profession and the Catholic Revival, 1660-1689," and John Bergin's "Irish Private Divorce Bills and Acts of the Eighteenth Century."

Saturday, November 28, 2009

Vintage Hovenkamp: The Classical Corporation in American Legal Thought

Classical political economy was dedicated to the principle that the state could best encourage economic development by leaving entrepreneurs alone, free of regulation and subsidy. The development of classical economic policy in the United States dramatically changed the concept of the business corporation. Within the preclassical, mercantilist model, the corporation was a unique entity created by the state for a special purpose and enjoyed a privileged relationship with the sovereign. The very act of incorporation presumed state involvement. State subsidy and the incorporators' public obligation were natural corollaries. Business firms that relied on the market alone to determine their prospects were simply not incorporated. As classical theory replaced the mercantilist model, the business corporation gradually evolved into a device for assembling large amounts of capital in a manner that could be controlled efficiently by a small number of managers. The classical model of the corporation did not emerge mature in a single decision. It evolved gradually in the nineteenth century, reaching its apogee in the 1880s and 1890s.The developing model of the classical corporation included two fundamental premises: (1) the corporate form is not a special privilege but merely one of many ways of organizing a business firm; and (2) the peculiar advantage of the corporation which the law should encourage is its ability to raise and concentrate capital more efficiently than other forms of business organization. These important developments formed the core of the classical corporate model: (1) the attack on the Marshall era contract clause; (2) the demise of the charter theory of business regulation; (3) the rise of the General Corporation Act and the decline of the special subsidy; (4) the application of the fourteenth amendment's protections to corporations; (5) the expansion of limited shareholder liability; (6) the narrowing scope of quo warranto and ultra vires; (7) the facilitation of multistate corporate business activities; and (8) the separation of ownership and control.

Schauer on Positivism Before Hart

Many contemporary practitioners of analytic jurisprudence take their understanding of legal positivism largely from Hart, and the debates about legal positivism exist largely in a post-Hartian world. But if we examine carefully the writings and motivations of Bentham and even Austin, we will discover that there are good historical grounds for treating both a normative version of positivism and a version more focused on legal decision-making as entitled to at least co-equal claims on the positivist tradition. And even if we think of the inquiry in philosophical and not historical terms, there are reasons to doubt the view that a theory of the nature of law is the exclusive understanding of the core commitment of legal positivism. Positivism as a descriptive theory of the nature of law is important, but so too is positivism as a normative theory about the preferable attitude of society or theorists, and so too is positivism as a normative or descriptive theory of adjudication and other forms of legal decision-making. Those who understand positivism and the positivist tradition as being more normative or more adjudication-focused than the contemporary understanding allows are not committing either historical or philosophical mistakes, and little would be lost were we to recognize the multiple important contemporary manifestations of the legal positivist tradition.

Olson on Extremism and Political Thought

This paper examines the use of the American jeremiad in the abolitionist and anti-abortion movements in the U.S. The American jeremiad is the lament, ubiquitous in political thought and culture in the U.S., that Americans are a chosen people who have failed to fulfill their calling, yet can still redeem themselves by returning to their moral and intellectual roots. Fanatics such as the abolitionist John Brown and anti-abortion activists Randall Terry, Paul Hill, and Scott Roeder embrace the structure and exceptionalism of the American jeremiad but, in contrast to political moderates, they insist on achieving the utopian ideals of the American jeremiad (unconditional emancipation, the outlawing of abortion) immediately rather than in the distant future. This leads them to reject political moderation and to embrace an extremist approach to politics.Olson, an Associate Professor of Politics and International Affairs is the author of The Abolition of White Democracy (University of Minnesota Press, 2004). He is at work on American Zealot, a book on the role of fanaticism in the American political tradition.

Friday, November 27, 2009

Comments temporarily turned off

Call for Papers: The Historical Society 2010 Conference

We especially encourage panel proposals, though individual paper proposals are welcome as well. And our interpretation of "panel" is broad: 2 or more presenters constitute a panel--chairs and commentators are optional. As at past conferences, we hope for bold yet informal presentations that will provoke lots of questions and discussion from the audience, not presenters reading papers word-for-word from a podium followed by a commentator doing the same. Please submit proposals (brief abstract and brief CV) by January 31, 2010 to Eric Arnesen, 2010 Program Chair, at jslucas@bu.edu.

Holloway on Disenfranchisement for Larceny in the Redeemer South

Between 1874 and 1882 all southern states (except Texas) amended their constitutions and revised their laws to disfranchise for petty theft. These revisions were part of a larger effort to disfranchise African American voters and to restore the Democratic party to political dominance in the region. This expansion of disfranchisement took the form of statutory revision, constitutional amendment, and judicial action. Some southern states changed their laws to upgrade misdemeanor property crimes to felonies. Felonies were already disfranchising offenses in most of these states. Several states amended or revised their constitutions to expand disfranchisement to include larceny and/or petit larceny. Two southern states that had never disfranchised for any crimes amended their constitutions to establish this penalty for the first time in the 1870s. Finally, southern courts interpreted existing laws to include misdemeanors as disfranchising crimes. While Democrats celebrated the success of these laws in disfranchising African Americans, Republicans criticized their racial and partisan impact. Although Democrats used a variety of techniques to ensure their electoral dominance, these new laws were one tool used by Democrats to deny the vote to Republicans in some of the most tightly-contested elections of this period. This article concludes with a discussion of the symbolic role that chicken theft played in discussions of petty theft. Experiences from the 1870s and 1880s demonstrate that partisan advantage can be obtained from laws disfranchising for crime, particularly when election officials with a partisan agenda exploit racially-skewed conviction and incarceration rates.

Thursday, November 26, 2009

Happy Thanksgiving!

Hat tip.

Hat tip.We have many things to be thankful for this year at the Legal History Blog. High on the list is you, dear reader. Thanks for visiting. That's what keeps the blog going.

The Legal History Blog will be back soon.

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

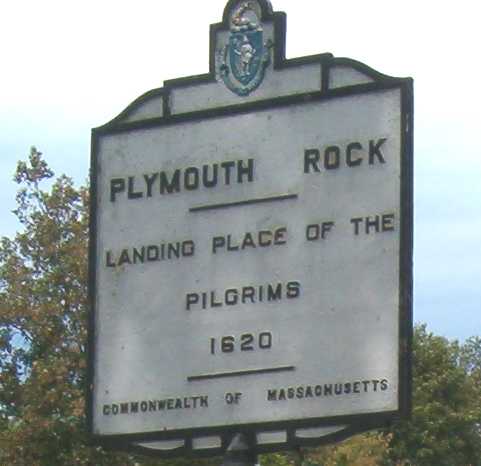

On the Pilgrims

As Americans prepare to stuff their faces with turkey, pie, turkey pie, and all manner of bread-related foods, and clock in millions of hours of TV football viewing, it’s worth considering the Pilgrims, originators of America's holiday....How do Pilgrims fit into American history and religious history in general?

How low the founders of our national myth have fallen. Nineteenth-century Protestants celebrated the Pilgrims as hearty, pure-of-heart forbearers. Yet even in the 19th century Pilgrims had their share of detractors....

In 1881, Mark Twain delivered an uproarious address, in the form of a plea, to the New England Society of Philadelphia. Why all this “laudation and hosannaing” about the Pilgrims? he asked his audience. “The Pilgrims were a simple and ignorant race. They never had seen any good rocks before, or at least any that were not watched, and so they were excusable for hopping ashore in frantic delight and clapping an iron fence around this one.” “Plymouth Rock and the Pilgrims” was a classic piece of Sam Clemens’ contrarianism. As the whole country went mad with Pilgrim fever, Twain shouted, “Humbug!”

Call for LHB Facebook Coordinator

og to have a Facebook presence. As with our Twitter feed, this would bring LHB content to a new space on the web. Having limited time for such things, your Legal History Bloggers would like some help from a Facebook-friendly reader.

og to have a Facebook presence. As with our Twitter feed, this would bring LHB content to a new space on the web. Having limited time for such things, your Legal History Bloggers would like some help from a Facebook-friendly reader.ASLH Meeting Highlights now Online

Charles Donahue, Jr., Harvard Law School, Past President of the American Society for Legal History and webmaster extraordinaire has posted details of the recent ASLH annual meeting in Dallas on the Society's webpage.

Charles Donahue, Jr., Harvard Law School, Past President of the American Society for Legal History and webmaster extraordinaire has posted details of the recent ASLH annual meeting in Dallas on the Society's webpage.Highlights of the meeting include election results and prizes, as well as photographs of the annual luncheon taken by Carol F. Lee. Among the news items:

- The ALSH website has a new address.

- The Law and History Review is moving from the University of Illinois Press to the Cambridge University Press, resulting in various changes.

The torch was passed, as President Maeva Marcus handed over the gavel to the incoming president, Constance Backhouse.

The torch was passed, as President Maeva Marcus handed over the gavel to the incoming president, Constance Backhouse.

Details about this year's program, including abstract for many of the papers, are here.

Info about next year's meeting in Philadelphia is here.

Photos by Carol F. Lee: Charles Donohue, Jr., President Maeva Marcus and incoming President Constance Backhouse.

Probert on Kept Mistressess and Cohabitation Contracts

This paper forms part of a wider project looking at the history of the legal treatment of cohabitants over the past 400 years. It begins with an examination of a set of cases often discussed under the umbrella of ‘cohabitation contracts’, and discusses how a contextual historical approach provides a different perspective on those cases. It then goes on to consider the legal approach to such arrangements, and the reasons, norms and assumptions that underpinned that approach. Finally, it discusses the relationship between law and behaviour – how far did the facts of these cases reflect the practice of the time?

Costello on Certiorari and Summary Convictions

The first sightings of the writ of certiorari being used as a means of attacking summary convictions can be found in the early-seventeenth century. This use of the remedy peaked in the early eighteenth century during the reign of George II. But even then the rate of usage was not high: there were barely more than four applications annually. It is likely no more than a few hundred convictions were ever removed by certiorari throughout the entire period 1660-1790.Image Credit: Sir John JervisDespite the relatively infrequent use of the remedy, from the late seventeenth-century onwards the employment of certiorari against criminal convictions attracted parliamentary attention and judicially-instigated procedural regulation. This account of certiorari and summary criminal convictions is concerned with three issues: (i) the measures adopted by parliament and the King’s Bench - the statutory recognisance, the no-certiorari clause, and, especially, the model form conviction - to limit this particular use of the writ; (ii) the nature of the review - review for formal defects on the face of the conviction - exercised by the King’s Bench when convictions were removed before it; and (iii) the reasons why convicted persons resorted to this expensive remedy to quash penalties for minor offences.

It concludes that the traditional account which identifies the model form conviction introduced by the Summary Jurisdiction Act 1848 as having killed off the remedy, exaggerates the effect of the 1848 Act. Sir John Jervis’s Act of 1848 did not terminate a flourishing jurisdiction. The 1848 Act was more of a tidying up measure; most convictions had already been rendered unreviewable.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Schmidt on The Debate over Law's Capacity and the Making of Brown v. Board of Education

From the late nineteenth into the mid-twentieth century, civil rights reformers fought, with little success, against the argument that law was powerless to change prejudicial attitudes and customs. It was widely assumed during the Jim Crow era that forcing the principle of racial equality on resistant southern whites might turn desegregation into yet another failed experiment in social reform by legal fiat — another Reconstruction or Prohibition. In the 1940s and 1950s, these assumptions began to give way because of the efforts of liberal scholars and activists who made the case that legal reform could be particularly effective at combating prejudice, and thereby improving race relations. Yet this struggle to overcome prevalent skepticism toward law’s capacity has been largely lost in historical scholarship. In this article I examine a generation of social scientists, historians, lawyers, and activists who made the case that race relations were more malleable than had been previously assumed and that properly conceived laws could affect not only outward behavior, but personal attitudes. Nowhere were these arguments more consequential than in the NAACP’s litigation campaign against segregated education. They provided an effective response to the fears of Supreme Court justices that a desegregation ruling would be ignored or, worse, rejected. I argue that the triumph of the idea that legal reform could reshape race relations was a critical factor in making possible the emergence of civil rights as a viable national issue in the early post-World War II period — and the great civil rights achievement of that era, Brown v. Board of Education.

Lavine on Berman v. Parker

The Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Berman v. Parker serves as the foundation for much of our modern eminent domain jurisprudence, including the controversial 2005 Supreme Court decision in Kelo v. New London. But the story behind the case starts well before 1954, and it carries implications that are relevant today. It’s a story that played out in many cities across the nation, just as it did in Washington, D.C., where the case took place. It’s the story of urban decay and urban renewal.

This working paper covers the history of redevelopment in Southwest Washington, from the turn of the century to today. It discusses the City Beautiful movement and progressive housing reform in Washington, the rise of public housing and slum clearance policies, the urban renewal planning process as it played out in Southwest D.C., and the demise of urban renewal as a federal policy in the wake of its failures. The conclusion points out while we may approach contemporary economic development projects differently than we approached urban renewal in the 50s and 60s, much can still be learned from the story behind this landmark case.

Ventry on the Mortgage Deduction

Image creditThis Article traces the mortgage interest deduction from accident to birthright, from one of many deductible personal interest items to one of the few left standing, and from a nominal tax offset to the second most expensive tax subsidy. It tells the story of how the mortgage interest deduction and other federal housing subsidies fueled the post-World War II surge in rates of homeownership and, more recently, how those programs contributed to the collapse of the housing and financial markets. Finally, the Article offers a eulogy to the mortgage interest deduction that draws on criticisms of the subsidy from two generations of tax reformers and tax policymakers that are more applicable today than at any time during the deduction’s nearly 100-year history.

Monday, November 23, 2009

Palmer on The Strange Science of Codifying Slavery

The Digest of 1808 was the first European-style code to be enacted in the Americas but it was also the first modern code anywhere in the world to incorporate slave law. The decision to combine the two subjects in a single code is curious and intriguing, and has not been explained. It is as if the Digest was to be the simultaneous expression of two contradictory impulses or perhaps two contrasting blueprints. It was, on the one hand, a code of enlightenment and natural reason, drafted shortly after the French and American revolutions, and embodying therefore all the acquis of those revolutions. On the other hand the Digest embodied slavery and was therefore a code of darkness, a code contra naturam, dedicated to the continuance of human bondage. The Digest of Orleans omitted sentimental, conscience-salving statements and made no apology for treating slavery. It has the tone of those who are comfortable in the right. Yet the task would seem problematic. Would not the juxtaposition of slavery in a liberal code produce a Janus-faced figure at war with itself? Was it possible to reconcile and unite the principles of liberal society with those of a slave-holding society? How would the slave be presented, as a person without rights or as human property without personality? How to reconcile the everyday contradiction that a slave could purchase his freedom, yet the law officially proclaimed that he or she was incapable of owning property, including that which he used in purchasing his freedom? Or how to reconcile that slaves were at times paid laborers (e.g., Sunday labor or hiring himself out in his free time) but remained enslaved the rest of the time? Could the code distinguish between the civil rights enjoyed by free whites and those rights held by free persons of color? Were those gradated distinctions even settled or understood in 1808 and what could be codified about them? One imagines that these must have been only some of the challenges facing Moreau Lislet, the principal draftsman.

Capozzola on ASLH panel: Circumnavigating the Pacific

On Friday morning, I participated in a session titled “Circumnavigating the Pacific: The United States and the Philippines, 1898-1945.”

Nancy Buenger, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Minnesota Law School, discussed “Home Rule: Equitable Justice in Chicago and the Philippines, 1898-1917.” Buenger argued that “home rule was a richly ambiguous slogan with an international pedigree,” and provocatively linked the concept with the rich traditions of equity jurisprudence in both Illinois and the Philippines. While many scholars have asserted the connections between domestic and imperial politics, Buenger documented these linkages with evidence ranging from intellectual history to legal biography.

“A Pacific ‘Quest for Power’: Governor General Forbes and the Rise of the Philippine Assembly, 1907-1913,” showed off the research of Anna Leah Fidelis Castañeda, who just completed her S.J.D. at the Harvard Law School. Drawing on a pathbreaking research project on Philippine political development that will mark her as one of the world’s leading scholars of Southeast Asian legal history, Castañeda showed how the members of the Philippine Assembly—Filipino elites who enjoyed limited suffrage rights—employed tactics that would have been familiar to any student of similar assemblies in colonial British North America. “Capitalizing on the need of American colonial actors to maintain ideological coherence, Filipino legislative leaders held their American tutors up to American principles to … hasten the pace of the tutelary program.”

Finally, Christopher Capozzola presented a paper on the tortuous history of postwar justice in the Philippines after World War II. “A Tale of Two Treasons: Adjudicating War Crimes and Collaboration in Manila, 1945,” explored the trial of Japanese General Yamashita Tomoyuki and his unsuccessful Supreme Court appeal in Yamashita v. United States (1945) alongside failed efforts to try Filipino collaborators in the Filipino People’s Court, an extraordinary court that briefly sat at war’s end. “Questions of imperialism and territoriality haunted both judicial undertakings,” I argued, and pointing to the use of Yamashita as a precedent for U.S. military commissions at Guantánamo Bay, I argued that “imperial problematics of territoriality and sovereignty continue to inform the legal structures of American power as it operates outside of U.S. territorial boundaries.

American legal historians have been paying attention to imperialism for some time now, but a full session devoted to some of the newest and most intensely archival research currently being done on the United States and the Philippines offered the audience new perspectives on a maturing subfield of U.S. and Asian legal history.

CFP: 2010 American Society for Legal History Conference

The Program Committee invites panel proposals in a wide variety of formats suited to 105-minute panel slots: Three papers and a comment; roundtable discussions of important subjects, projects or books; “author meets reader;” panels with more than three presenters who give short papers (10 minutes) without commentator; and other formats suggested by submitters.

The Program Committee invites early career scholars (including graduate students) and other scholars who have not been on the ALSH Program before to consult with the Co-Chairs of the Program Committee for advice in constructing a panel, including how to identify and contact others working in your field. Please send inquiries to Kenneth F. Ledford (kenneth.ledford@case.edu) or Barbara Y. Welke (welke004@umn.edu).

Panel proposals should include the following:

-- an abstract of the paper of no more than 300-words; and

-- a one-page c. v. or biography for the author, including complete contact information; please note whether this person appeared on the 2009 Program and in what capacity.

The deadline for proposals will be February 28, 2010. Proposals (preferably in a single PDF file, but acceptable in Word or WordPerfect) should be sent as email attachments to Kenneth F. Ledford at kenneth.ledford@case.edu. Those unable to send proposals as email attachments can mail hard copies to:

2009 ASLH Program Committee

c/o Kenneth F. Ledford

Department of History

Case Western Reserve University

11201 Euclid Avenue

Cleveland, OH 44106-7107

U.S.A.

Sunday, November 22, 2009

Sunday book news

cent book news:

cent book news: Sean Wilentz, "Into the West," NYT, 20 November, reviews Robert W. Merry's A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent.Ralph is collecting nominations through November for the best in history blogging.

Jonathan Yardley, "Forgotten Warrior," Washington Post, 22 November, reviews Joan Waugh's U. S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth.

Janet Maslin, "The Queasy Side of Theodore Roosevelt's Diplomatic Voyage," NYT, 18 November, reviews James Bradley's The Imperial Cruise: A Secret History of Empire and War.

Oliver on the History of Witnesss Detention

With the Ninth Circuit's opinion in al-Kidd v. Ashcroft holding that material witness detentions may not be used as a pretext to hold suspects, it is worth noting that as a practical matter the power has never been used any other way. The practice dates make to the 1840s as professional police departments were being created. In the mid-nineteenth century policing was becoming a career. For the first time, there were incentives to investigate crime; law enforcement provided opportunities for long-term retention and promotion. Officers employed by newly-established police departments began to aggressively investigate crime using powers unimaginable to their constable and night-watch predecessors. Among these new powers was the ability to detain material witnesses. Officers began to detain suspects, whom they lacked adequate suspicion to charge, as witnesses. As the public became aware of the incarceration of those identified only as "witnesses," officer found the public very unwilling to cooperate in investigations for fear of being held for the crime of possessing helpful information. In New York, the Police Department asked the legislature in the late nineteenth century to allow only the detention of witnesses suspected of being accomplices. The legislature's acquiescence to the law enforcement request demonstrates not only the rising influence of law enforcement interests in the late-nineteenth century, it also demonstrates that the public was comfortable with material witness detentions only when they were used as a pretext to hold suspects.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

The Case of the Thirsty Mollusk

I learned recently of the BBC radio series, The Cases That Changed Our World. The latest episode is "The legal case of the snail found in the ginger beer ," Donoghue v Stevenson (1932).

I learned recently of the BBC radio series, The Cases That Changed Our World. The latest episode is "The legal case of the snail found in the ginger beer ," Donoghue v Stevenson (1932).Image credit.

The Automated Academic

Hat tip to Bill Garcia, University of Chicago Law School, Class of 1983.

Friday, November 20, 2009

Sweeny on ASLH Panel: Biography and Legal History

Society for Legal History panel on Biography and Legal History.

Society for Legal History panel on Biography and Legal History.This panel varied widely in its focus, with the main theme being the examination of a particular person’s life and how that person influenced the formation of law. The panel was decidedly international and presented the fascinating stories of judges and attorneys around the world.

Catharine MacMillan (Queen Mary, University of London) presented a paper entitled “Judah Benjamin: An Émigré Barrister and International Law,” which explores the life of the well-studied member of the Confederate government after he fled to England. Professor MacMillan takes up Benjamin’s story after most historians have left it and explores how Benjamin profoundly influenced British commercial and international law. Benjamin represented British companies and citizens who were instrumental in helping fund the Confederate government and, in so doing, Benjamin caused the British courts to confront principles of international law for essentially the first time when they recognized, against the United States’ objections, that the Confederate government was a legitimate government capable of entering into contracts with British citizens.

Grant Morris’s (Victoria University of Wellington) paper entitled “Chief Justice James Prendergast and the Treaty of Waitangi: Judicial Attitudes to the Treaty in New Zealand during the Latter Half of the Nineteenth Century” focuses on a famous case in New Zealand wherein Chief Justice Prendergast ruled that the Waitangi treaty, in which set the terms of land ownership between the Maori people and the British crown, was a “legal nullity.” This holding basically extinguished the Maori’s claims of ownership to any New Zealand land and instead gave them “occupation rights” to land that belongs to the British sovereign. The holding (and Prendergast himself) has been recently criticized for its negative treatment of the Maori people but Professor Morris places this decision in its historical context. In doing so, Morris shows that Prendergast is not necessarily the villain he has sometimes been portrayed as, but is a man that failed to rise above the anti-native prejudices of his

time.The third paper presented was by David Marcus (University of Arizona) entitled “Charles Clark, Legal Realism, and the Jurisprudential Basis of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.” This paper focused on the main author of the Federal Rules, Charles Clark, and attempted to reconcile Clark’s legal realist philosophy with the formal approach taken by the Federal Rules. Academics have found a discrepancy between legal realism, which essentially posits that judges are swayed by their own beliefs and not some overarching concept of the “right decision,” and the Federal Rules, which appear to presume that judges will simply follow rules and not their own hearts. Professor Marcus is able to find a connection between these two concepts by showing that Clark’s legal realism allowed him to transcend prior procedural rules and focus on what would actually be effective and efficient for judges and litigators. The Federal Rules are therefore seen as means instead of ends unto themselves and they give enough discretion to judges to allow them to reach effective real-world outcomes.

The final Paper was Polly Price’s (Emory University) “‘The Intensely Practical Nature of the Political Process’: Judge Richard S. Arnold’s Legislative Role in the Third Branch,” which is part of a larger biography she is writing about Judge Arnold. Professor Price focuses on Judge Arnold’s background as a failed politician and shows how the knowledge of the political system he gained when running for elected office helped him in his judicial role. Judge Arnold used his experience when deciding the seminal case Jeffers v. Clinton, wherein he held the Voting Rights Act required the state of Arkansas to modify its apportionment plan for the next election to create more legislative positions in districts where the population was predominantly African American. Judge Arnold’s political experience also helped him as chairman of the Budget Committee of the Judicial Conference when he appeared before Congress to address the judiciary’s budget concerns.

The commentator for this panel was Paul Kens (Texas State University, San Marcos) who attempted to weave together these very distinct historical personages. For example, he noted that Judah Benjamin and Justice Prendergast were both involved in defining what constituted a nation that could engage in contracts.

Questions from the audience focused on some of the more interesting details of the biographical subjects’ lives such as Judah Benjamin’s life in New Orleans and Charles Clark’s academic writings on legal realism.

Walker on Justice Powell

Walker is the author of The Ghost of Jim Crow (Oxford University Press, 2009).Though diversity remains a compelling state interest, recent rulings like Ricci v. DeStefano and Parents’ Involved toll a menacing bell for schools employing racial classifications to admit minority students. Yet, defenders of diversity may find refuge in original meanings, particularly the original meaning of diversity as articulated by Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. in Regents v. Bakke in 1978. Virginian by birth, Powell’s interest in “genuine diversity” coincided with a forgotten version of pluralism extant in the American South during the first half of the Twentieth Century. Further, Powell’s conviction that diversity distinguished America coalesced during a trip to the Soviet Union in 1958. Recovering Powell’s pluralism not only sheds new light on the Justice, but might hold the key to new ways of thinking about diversity generally in university admissions.

Image credit.

Rosen on Unwanted Copyrights

Hat tip: Cohen, et al., Copyright in a Global Information EconomyThis article traces the development of copyright law in commercial prints and labels, looking at the history of the 1874 Act which placed registration of copyrights in the Patent Office (the "unwanted" copyrights because the Library of Congress had no desire for them), as well as the two Supreme Court cases which dealt with this act - Higgins v. Keuffel and Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing [concerning the image at left]. In so doing the development of the scope of copyright law in both the constitutional and normative senses is addressed, specifically the importance of the preamble to the intellectual property clause as a substantive limit of Congressional legislation in the nineteenth century. Statistics are also included, demonstrating the development and use of this copyright law.

Thursday, November 19, 2009

Tani and Stein on ASLH Panel: Civilizing and Un-Civilizing War in the Nineteenth Century

Another highlight of the 2010 ASLH annual meeting was a panel titled “Civilizing and Un-Civilizing War in the Nineteenth Century, ” chaired by Richard Ross (University of Illinois). The panel explored the notion of war as an atavistic but arguably effective form of dispute resolution.

Stephen Neff, University of Edinburgh opened the panel with a paper on “Partisans, Prowlers and Guerillas: Historical Roots of International Law on Unlawful Belligerency.” The paper keyed in on one major innovation of nineteenth century warfare: guerilla-style combat by self-appointed persons. This was a departure from the “civilized” traditions of pitched battle, professional armed forces, and commissioned fighters. As evidence, Neff cited the work of German-American jurist and political scientist Francis Lieber. In Lieber’s influential treatise on the laws of war, Lieber took pains to differentiate partisans – individuals authorized to fight but separate from the armed forces – from various categories of non-authorized combatants (brigands, prowlers, civilian saboteurs, etc.). The former were entitled to prisoner-of-war protection; the latter (with the exception of “spontaneous self-defenders”) were not. To Neff, this represented a very “eighteenth-century view” of warfare, and indeed by 1874, governments departed from this aspect of the Lieber Code. They agreed that self-appointed groups would receive protection if they were organized and open. Thus “civil” conduct in war began to replace official commissions as the key indicator of legitimacy. Neff closed his presentation with an intriguing question about warfare in the twenty-first century: in our concern about combatants who lack national sponsorship, might we discern another shift in our understanding of the legal bounds of war?

James Whitman (Yale University), like Stephen Neff, did not shy away from making far-reaching arguments about the laws of war. His paper, “The Breakdown of Battle Culture, from Waterloo to Sedan,” traced a movement from the eighteenth century’s “admirably civilized” style of warfare (characterized by pitched battles) to a regime of tactics aimed at annihilation. Napoleonic warfare, he noted, was the beginning of the end of this “golden age,” because of Napoleon’s locust-like armies and destructive campaigns. Why did this transformation occur? By way of answer, Whitman discussed how opposing forces adopted a more “civilized” style of battle in the first place. Whitman suggested that during the eighteenth century, pitched battle was an accepted form of dispute resolution; it seemed to have particular legitimacy when disputes involved dynastic succession or territorial claims. At some point, however, the participants began thinking of themselves in millenarian terms: they were fighting to “make history.” Whitman proposed that this changed understanding of lawful warfare was hastened by the disappearance of pre-modern legal culture.

The third paper, by John Witt (Yale University), nicely complemented the others. Titled “Rules of Wrong: The Crisis of the laws of War in the Age of Democratic Ideals,” Witt’s paper focused on how U.S. politicians invoked international law, and the law of war in particular, during the first half century of nationhood. Witt challenged what he called the “weak state, new state” theory – the notion that fragile, fledgling states would invoke the law of nations because of their vulnerability. Witt argued that, while valuable, the prevailing understanding of weak states has difficulty accounting for leaders like Andrew Jackson. Witt detailed how Jackson, as the elected general of the Tennessee militia, encouraged his men to engage in ferocious, terroristic conduct. By all accounts, Jackson had nothing but contempt for the laws of war. Yet at certain moments Jackson invoked these standards of conduct for political advantage. In his campaign in Florida, for example, he invoked the law of war to justify his escalation of violence against those who challenged American sovereignty. Witt concluded by drawing a connection to the rejection of the Lieber Code by pacifists in the antebellum era. While laws of war were arguably a means of peace-keeping, they had learned from the Jacksons of the world that such a framework was ultimately a license for bloodshed. In their eyes, the treatises of American jurists like James Kent, who aimed to outline the “Law of Nations,” only served to provide legal rationalization for unabashed warmongers.Adam Kosto, Columbia University, provided an excellent comment. As an historian of medieval Europe, he was able to offer a “long view” of the questions involved. For example, he noted that the effort to draw lines between combatants and non-combatants, the focus of Neff’s paper, has an antecedent in the medieval tradition of not attacking those who were, in the eyes of war-makers, economic resources. (Kosto also noted that after the eleventh century, chivalric customs protected nobles and knights, a perversion of contemporary understandings of who ought to be shielded most during times of war.) Kosto also found medieval referents for some of the questions that Whitman and Witt raised. Regarding pitched battles as a recognized form of dispute resolution, he noted that in the middle ages war was understood as a branch of contract law.

Questions from the audience were diverse and thoughtful. Ross pressed the panelists to consider the colonial context and how the fighting of indigenous people may have contributed to the transformations they identified. The panel was also asked about their “landlubbers bias” (on account of their lack of attention to sea-based warfare and piracy), their insights into twentieth century wars, and the use of the terms “civilized” and “uncivilized” in an age of empire. They also faced a more existential question: given the shifting but persistent mismatch between the law of war and the practice of war, do legal rules have any meaning at all in this context?

Finally, it bears noting that this panel was all male, while an earlier panel on “Gender, Soldiering, and Citizenship” consisted entirely of women. We hesitate to speculate too much about these gender imbalances, but it does give us pause. What might this suggest about the historical study of war?

Skowronek on the Unitary Executive

This Essay traces successive elaborations through to the most recent construction of presidential power, the conservative insurgency’s “unitary executive.” Work on this construction began in the 1970s and 1980s during the transition from progressive to conservative dominance of the national agenda. A budding conservative legal movement took up the doctrinal challenge as an adjunct to the larger cause, and in the 1990s, it emerged with a fully elaborated constitutional theory. After 2001, aggressive, self-conscious advocacy of the unitary theory in the Administration of George W. Bush put a fine point on its practical implications. Much has been written about this theory in recent years, but virtually all of the commentary is by legal scholars seeking to adjudicate the constitutional merits of the case. That is to say, commentators have been debating the soundness of the theory’s claims as an interpretation of texts and precedents. The objective here is different. It is to situate the theory in the long line of insurgent constructions and to address it more directly as a political instrument and a developmental phenomenon.

The guiding assumption of this analysis is that a new construction of the presidency gains currency when it legitimizes the release of governmental power for new political purposes. I do not mean to suggest that candid reckoning with construction as a political process disposes of the constitutional claims of the unitary theory or of any other theory for that matter. I contextualize these claims in order to bring other issues to the fore. Significance is to be found in the practical political problems that conservative insurgents had to confront in venting their ambitions, in the sequence of prior constructions on which their response to these problems was built, and in the cumulative effects of the developmental process of construction itself.

ASLH: The Surrency Prize

The Surrency Prize for 2008 is awarded to Gautham Rao for “The Federal Posse Comitatus Doctrine: Slavery, Compulsion, and Statecraft in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America.”

Historians have long acknowledged slavery’s pivotal role in shaping the contours of early American society. Recent scholarship, however, is just beginning to reveal the true depth and breadth of that influence, detailing very specifically the myriad ways in which the institution influenced conceptions of republicanism, democracy, citizenship, race and union. Now comes Gautham Rao’s “The Federal Posse Comitatus Doctrine: Slavery, Compulsion, and Statecraft in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America” to add another dimension to the story.

Gautham’s article stood out to committee members for the breadth of its research, the creativity of its argument, and the fluidity of its presentation. Rao explores the ways in which federal coercion under the posse comitatus doctrine in the 18th and 19th centuries continually forced white Americans to ponder the relationship between citizens and their government in a new nation still testing the boundaries between federal and state power. Very critically, this exploration took place in a world marked by chattel slavery. The institution gave white citizens a handy point of reference to help define what it meant to be free and what it meant to be enslaved. This was no mere abstraction. The history of the “posse comitatus doctrine”, Rao argues, “suggests a foundational relationship between slavery and the federal government’s techniques of coercing free individuals.” Rao deftly recounts the ways in which white southerners used the doctrine to protect their property interest in human beings, using the deputizing power of the Fugitive Slave Act to force often unwilling northerners to return people who had escaped from slavery. They then fought effectively against its application when the tables turned and the victorious north sought to use federal power to establish equality under the law for the freed men and women of the south. Rao’s piece provides fertile grounds for discussion of its argument, but also suggests further avenues of inquiry about the ways in which the historical uses of the posse comitatus doctrine still influence us today.

Hat tip: H-Law

ASLH: The Sutherland Prize

The Sutherland Prize, named in honor of the late Donald W. Sutherland, a distinguished historian of the law of medieval England and a mentor of many students, is awarded annually, on the recommendation of the Sutherland Prize Committee, to the person or persons who wrote the best article on English legal history published in the previous year.

The Sutherland Prize for 2008 is awarded to Paul D. Halliday and G. Edward White for their joint article, “The Suspension Clause: English Text, Imperial Contexts, and American Implications,” 94 Virginia Law Review 575-714 (2008).

The Suspension Clause article persuasively lays out and documents the “franchise” argument – that the Great Writ (as habeas corpus has often been called) must be understood historically as having been a feature of the royal prerogative, allowing the king, or the king’s courts, to demand an explanation for the detention or imprisonment of the king’s subjects throughout the king’s dominions. The article makes it clear that “subjecthood” encompassed all those who could lay claim to the king’s protection, whether alien or citizen. Professors Halliday and White emphasize the important fact that the famous habeas corpus statute of 1679 “was never understood, in the period before the American framing, as superseding the common law habeas jurisprudence.”

The seminal writing of Matthew Hale then supplies the foundation for the explanation by Professors Halliday and White of the far-reaching geographical scope of the writ. The format for the explanation is to “take a tour across the king’s dominions, beginning within the English realm then traveling well beyond it, with Hale as our guide.” This is followed by the revealing and important description of habeas corpus in colonial India. After circling the globe, Professors Halliday and White turn to the Suspension Clause, having provided clear perspective on how the British Americans would have understood habeas corpus, and how it “had been reframed” so that it “was no longer associated with the prerogative” but instead was “thought of as a power exercised by individual judges as well as courts.” The article is based upon exhaustive documentary research and is a splendid example of the enhanced historical understanding that can be gained through the patient archival work of the legal historian.

Hat tip: H-Law

Huhn on Slaughterhouse, Bradwell and Cruikshank

The Slaughterhouse Cases, Bradwell v. Illinois, and Cruikshank v. United States, which were all decided between 1873 and 1876, were the first cases in which the Supreme Court interpreted the 14th Amendment. The reasoning and holdings of the Supreme Court in those cases have affected constitutional interpretation in ways which are both profound and unfortunate. The conclusions that the Court drew about the meaning of the 14th Amendment shortly after its adoption were contrary to the intent of the framers of that Amendment and a betrayal of the sacrifices which had been made by the people of that period. In each case the Court perverted the meaning of the Constitution in ways that reverberate down to the present day.

n these cases the Court ruled upon several critical aspects of 14th Amendment jurisprudence, including (1) Whether the 14th Amendment prohibits the States from interfering with our fundamental rights; (2) How the equality of different groups should be determined; and (3) How much power Congress has to protect the civil and political rights of American citizens - in particular, whether the 14th Amendment authorizes Congress to enact legislation to prevent mobs or other private individuals from violating people’s fundamental rights. The Court narrowly construed the constitutional principles of liberty, equality, and the power of Congress to protect civil rights.

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

AHA Book Prizes Announced

The latest issue of the AHA Perspectives on History brings word that Laura F. Edwards, Duke University, has won the American Historical Association's Littleton-Griswold Prize in American Law and Society for The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South (University of North Carolina Press). (Edwards discussed her researching and writing of the book here and here.)

The latest issue of the AHA Perspectives on History brings word that Laura F. Edwards, Duke University, has won the American Historical Association's Littleton-Griswold Prize in American Law and Society for The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South (University of North Carolina Press). (Edwards discussed her researching and writing of the book here and here.)The Prize was not announced at the annual meeting of the American Society for Legal History, but at the ASLH's annual luncheon Hendrik Hartog, Princeton University, chair of the AHA committee, read the following statement:

We write as individual members of the ASLH. We served this past year as members of the selection committee of the Littleton-Griswold Book Prize awarded by the American Historical Association. Early in our deliberations we considered whether the new three volume Cambridge History of the Law in America, edited by Christopher Tomlins and Michael Grossberg, should be included in our deliberations. In the end we decided that it should not, that we wanted the prize to remain as it had been for many years: a prize for the best monograph in American legal history.The other members of the committee were Dan Hamilton, University of Illinois-Champaign Law School, Sally Hadden, History, Florida State University, Karl Jacoby, History, Brown University, and Tom Mackey History, University of Louisville.But all of us felt that the publication of these three volumes should not go unmarked and uncelebrated. The extraordinary readability and the synthetic power of many of the essays in the volumes are reason enough for celebration. The conceptual frameworks that the editors have introduced--among others, the central significance of a "long nineteenth century," and the imperial and Atlantic world focus of the first volume--will mark our field for a generation. Every sentient legal historian will find something to argue with and about in these volumes. Some of us will want to challenge the synthetic enterprise itself, perhaps on the grounds of prematurity, perhaps out of belief that a project dedicated to generalizations about the history of law "in America" is either too broad or too narrow. The volumes clearly and precisely capture a particular historiographic moment, and one can be certain that our field will soon view that moment as one that has passed. Still, the appearance and availability of these volumes is not just one more measure of the amazing vitality and energy of our field. The Cambridge History of the Law in America will remain, we are confident, a permanent monument to our growth and maturation as a discipline.

Other works of or closely related to legal history that won AHA book awards include Karl Jacoby, Brown University, for Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History (Albert J. Beveridge Award; Penguin Press); Peggy Pascoe, University of Oregon, for What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (William H. Dunning Prize; Oxford University Press); Klaus Mühlhahn, Indiana University, for Criminal Justice in China: A History (John K. Fairbanks Prize in East Asian History; Harvard University Press); and Thomas J. Kuehn, Clemson University, for Heirs, Kin, and Creditors in Renaissance Florence (Helen and Howard R. Marraro Prize; Cambridge University Press).

Other works of or closely related to legal history that won AHA book awards include Karl Jacoby, Brown University, for Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History (Albert J. Beveridge Award; Penguin Press); Peggy Pascoe, University of Oregon, for What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (William H. Dunning Prize; Oxford University Press); Klaus Mühlhahn, Indiana University, for Criminal Justice in China: A History (John K. Fairbanks Prize in East Asian History; Harvard University Press); and Thomas J. Kuehn, Clemson University, for Heirs, Kin, and Creditors in Renaissance Florence (Helen and Howard R. Marraro Prize; Cambridge University Press).Hat tip: H-Law

Sweeny on ASLH panel: Exceptional Women in the Medieval Courtroom

Exceptional Women in the Medieval Courtroom

This panel focused on the unique place women had in the court room during the Middle Ages in Spain, France and Italy. Each paper presented a difficult legal situation involving women that required courts to adapt or change the law in order to properly address the issue.

Marie Kelleher (California State University, Long Beach) presented a paper entitled “Facing off from the Margins: Female Slaves and Jews in Medieval Procedural Law,” which focused on a single, though fascinating, case in late medieval Barcelona that presented a tricky procedural issue for the courts due to the limitations placed on women who witnessed a crime. In the case of adultery at issue in Professor Kelleher’s paper, the only two witnesses available were women, who were traditionally prohibited from testifying in criminal cases. Faced with a dilemma of two substandard witnesses who contradicted each other’s testimony, the judge in the case was forced to innovate by having each woman testify while looking the other witness in the eye, wherein it was hoped that the liar’s body language would give her away. Professor Kelleher concluded that this “hard case” is an example of how judges were willing to innovate with regard to procedural rules, particularly because Barcelona had large slave and Jewish populations, which meant that this issue was likely to reoccur.

Jamie Smith (Alma College) presented a paper entitled “Avoiding Great Harm, Danger, and Absurdity: Legal Protection for Wives with Absent Husbands.” This paper concerned the legal plight of Genoese wives whose husband’s went on long naval voyages. Wives were unable to conduct business, even regarding their own property, without their father and husband’s consent. Professor Smith showed how the law evolved to allow women increased freedom to engage in monetary transactions costing more than ten lire, providing they had other proper witnesses that would testify to their husband’s absence and approval of the transaction. A hardship clause was also introduced to allow a woman to manage her husband’s affairs if he were gone for more than three years. According to Smith, these changes in the law show that the legal system was willing to accommodate women as well as the larger community, which wanted to encourage men to embark on these profitable naval journeys.

Sara McDougall (Yale University) presented a paper entitled “Abandoned Wives and the Law in Late-Medieval Champagne.” Using court registers, Professor McDougall was able to reconstruct detailed and fascinating accounts of the private lives and legal travails of three women whose husbands went missing but later returned to find their wives had remarried. At first, the law accepted a woman’s belief that her husband was dead but later changed to require evidence, which, depending on the circumstances, could be impossible to provide. These case studies show how ecclesiastical courts attempted to police marriage in the midst of the chaos resulting from the 100 Years War.

Susan McDonough (University of Maryland, Baltimore County) provided unifying commentary by noting that these exceptional women were not truly exceptional because they represented reoccurring problems within the legal community. She also focused on the importance of community perceptions and legal legitimacy for each paper.

Among other things, commentators brought up the point of the difference between legal courts and ecclesiastical courts and how the two might combine in the presenters’ cases.

The Cromwell Book and Dissertation Prizes

For the book prize, the committee unanimously recommended Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941 (Cambridge University Press, 2008). McLennan sheds new light on the history of prisons and punishments from the early republic through the Progressive era by focusing on convict labor. She brings into sharp focus the complex and changing relationship between punishment, work, politics, and economics. The tensions between the conflicting goals of discipline, penitence, and profit provoked clashes between prison administrators, penal reformers, and inmates. McLennan successfully strikes a balance many historians seek but few achieve between granting agency to those who lack access to conventional forms of power and identifying the very real limits of that agency. Even after Progressive era reforms abolished prisoners’ involuntary servitude and replaced it with an incentivized system of behavioral rewards and punishments, the penal system still sought to profit from the unfree while preparing them for freedom. McLennan’s “crisis of imprisonment” persists.

For the book prize, the committee unanimously recommended Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941 (Cambridge University Press, 2008). McLennan sheds new light on the history of prisons and punishments from the early republic through the Progressive era by focusing on convict labor. She brings into sharp focus the complex and changing relationship between punishment, work, politics, and economics. The tensions between the conflicting goals of discipline, penitence, and profit provoked clashes between prison administrators, penal reformers, and inmates. McLennan successfully strikes a balance many historians seek but few achieve between granting agency to those who lack access to conventional forms of power and identifying the very real limits of that agency. Even after Progressive era reforms abolished prisoners’ involuntary servitude and replaced it with an incentivized system of behavioral rewards and punishments, the penal system still sought to profit from the unfree while preparing them for freedom. McLennan’s “crisis of imprisonment” persists. For the dissertation/article prize, the committee unanimously recommended Jed Shugerman, “The People's Courts: The Rise of Judicial Elections and Judicial Power in America” (PhD thesis, Yale University, 2008). Shugerman’s dissertation breathes new life into a neglected topic: judicial elections. Extraordinarily well researched, the dissertation explores why this uniquely American institution both shaped and reflected myriad changes in 19th century political, economic, and legal life. Shugerman’s historical periodization supports the new and persuasive claim that electing state judges emerged as a check on executives and legislatures abusing discretion, especially during the era of Jacksonian Democracy. Judicial elections thus strengthened judicial review and engendered a sharp increase in the number of statutes invalidated on constitutional grounds.

For the dissertation/article prize, the committee unanimously recommended Jed Shugerman, “The People's Courts: The Rise of Judicial Elections and Judicial Power in America” (PhD thesis, Yale University, 2008). Shugerman’s dissertation breathes new life into a neglected topic: judicial elections. Extraordinarily well researched, the dissertation explores why this uniquely American institution both shaped and reflected myriad changes in 19th century political, economic, and legal life. Shugerman’s historical periodization supports the new and persuasive claim that electing state judges emerged as a check on executives and legislatures abusing discretion, especially during the era of Jacksonian Democracy. Judicial elections thus strengthened judicial review and engendered a sharp increase in the number of statutes invalidated on constitutional grounds.Shugerman ascribes the dynamics of change more to pro-and-antislavery politics and contests over strict liability than to the self-centered role of elite lawyers. Ultimately, his impressive work invites new research on the relationship among modes of judicial selection, constitutional checks-and balances, and substantive legal rules.

[The Harvard Law School’s release on Shugerman’s prize is here.]

Hat tip: H-Law