|

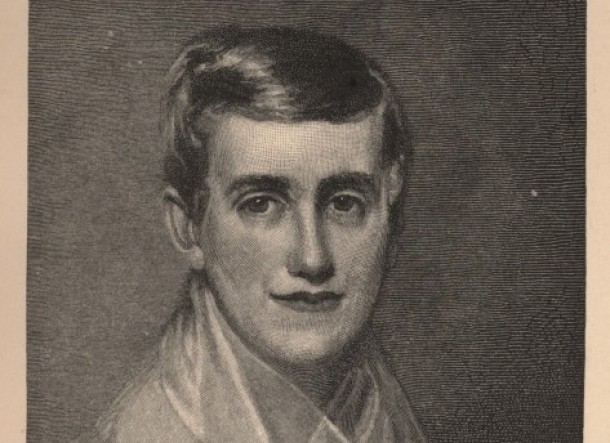

| Frank Sworn in as SEC Chairman Douglas Looks On (LC) |

The font of the “about-face narrative” is Jerome Frank’s remark, in If Men Were Angels (1943), “The reader of Pound’s earlier writings, indeed, rubs his eyes when he peruses Pound's 1940 volume [Contemporary Juristic Theory] ‘Can this be the same man?’ he asks.” Rarely does whoever cites the passage acknowledge that Frank’s book, dedicated “to Mr. Justice William O. Douglas who, while Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, superlatively demonstrated that effective administration can be made an important instrument of true democracy,” was anything but a dispassionate review of Pound’s writings on administrative law. It was, rather, a shot in a running gun battle between the former dean and his New Deal critics.

Jerome Frank’s career and the origins of his jurisprudential quarrel with Roscoe Pound are well known–or easily knowable from the works of Neil Duxbury, Robert Jerome Glennon, N.E.H. Hull, and Laura Kalman. Even before publishing his sensational Law and the Modern Mind (1930), Yale law professors referred to him as “our sort of practitioner,” one who had “become adept at the art of advocacy without ceasing to be the intellectual adventurer.” In particular, Frank had both an insider’s understanding of the corporate reorganization practice and a revulsion against the wealth it brought its most forceful practitioners, such as Robert T. Swaine of the Cravath firm. In this, he was much like Yale’s William O. Douglas, who had experienced the corporate reorganization practice at Cravath. The two collaborated on law review articles that drew Swaine’s fire.

As Hull in particular relates, in the early 1930s, Frank’s jurisprudential sallies, in which Karl Llewellyn sometimes joined, provoked Pound’s ire. While still dean of the Harvard Law School, he usually regained his composure and believed his capacious jurisprudence would contain the radical implications of the legal realists’ work. His equanimity survived the U.S. Supreme Court’s revamping of the Contract and Due Process Clause in the Blaisdell and Nebbia decisions of 1934. 1937 changed all that. Pound did not join in the fight over the Court-packing plan, announced the day he left San Francisco on an around-the-world trip, but it and the presence of Frank, Douglas and other legal realists in the Roosevelt administration made him fear that the “give-it-up” philosophies of his jurisprudential rivals might prevail. (That James Landis, his successor as HLS dean, had supported FDR’s plan, was particularly galling.) When incoming ABA president Arthur T. Vanderbilt offered Pound the chairmanship of the Special Committee on Administrative Law, the former dean hesitated only briefly before accepting. (The encouragement of Joseph N. Welch, better known for his magnificent role in the Army-McCarthy hearings, proved decisive.)

In the quarrel following the circulation of Pound’s report in the summer of 1938, heat predominated over light. Pound repeatedly displayed the willful solipsism indistinguishable from dishonesty that had infuriated the HLS faculty in his final years as dean. He pretended that Vanderbilt did not expect him to draft a statute as well as a statement of first principles, even though any reader of their correspondence could see that Vanderbilt did. In his report, Pound cited Swaine as an objective commentator on the dangers of “politically constituted administrative bureau” without acknowledging that the Cravath lawyer, Douglas (then serving as SEC chairman), and Frank (an SEC member) had a history. With Stalin’s show trials just concluded and the House Un-American Committee just beginning its investigations, he professed amazement that anyone would see his characterization of his rivals as Marxists as dangerous Red-baiting when the legal philosopher Morris R. Cohen politely pointed out that it was just that. After the report came out, he told Frank he did not mean to single out the SEC even though he had just brought an audience of investment bankers to its feet by blasting Frank and his agency.

In his replies, Frank was far from a model of scholarly detachment. If Pound accused administration of

sheltering dangerous official discretion, Frank returned fire with the tu quoque argument that at least the SEC’s staff did not use the rubber hose on its adversaries as did police under the judiciary’s negligent oversight. Even the SEC’s general counsel thought another, similar riposte to be “hitting below the belt.” And, as the dedication of If Men Were Angels suggests, Frank could be excessive in heroizing Douglas. At the ABA meeting that received Pound’s report, Frank declared that “patient justice is a quiet virtue with” Douglas. (“Of course it is,” I can’t help saying to myself. “Just ask any of his wives.”)

sheltering dangerous official discretion, Frank returned fire with the tu quoque argument that at least the SEC’s staff did not use the rubber hose on its adversaries as did police under the judiciary’s negligent oversight. Even the SEC’s general counsel thought another, similar riposte to be “hitting below the belt.” And, as the dedication of If Men Were Angels suggests, Frank could be excessive in heroizing Douglas. At the ABA meeting that received Pound’s report, Frank declared that “patient justice is a quiet virtue with” Douglas. (“Of course it is,” I can’t help saying to myself. “Just ask any of his wives.”)Of the two, Frank had the better understanding of the stakes. American lawyers were going to reach an accommodation with the administrative state regardless of what an ex-law dean said or did. Yet when the ABA’s proposal was introduced in Congress as the Walter-Logan bill in early 1939, the recent history of the antibureaucracy clause threatened to repeat itself, only to devastating effect. Congress had largely ignored the ABA’s proposals to reform administrative procedure for years, but after FDR’s attempted purge of party rivals in the 1938 primaries, congressional leaders saw it, the Hatch Act and an investigations of the NLRB as ways to reduce the power of “third termites” in the executive departments and administrative agencies. The Walter-Logan bill need not enact Dicey’s rule of law; it would suffice if it tied up the NLRB, the SEC, and the Wage and Hour Division while courts worked out sensible interpretations of its ambiguous provisions. (In this sense it was “a ripper bill,” as an early student of the measure once characterized it to me.) The politicians, prompted by one of Pound’s acolytes, Judge Harold Stephens of the DC Circuit, were also shrewd enough to realize that Pound’s imprimatur could cloak their partisan calculations. No one “stands out more indisputably above the clamors and passions of the day,” one declaimed. “When he speaks in terms of our national future, all of us, Republican, Democrat or dissenter, must pay heed.”

If Pound in his “anecdotage” (Jerome Frank) was thus willing to lend his “great name to one side of an important controversy” (Kenneth C. Davis), then he “had it coming to him” (James Landis). A generation of liberal legal academics proved more than happy to do the honors. Lost in the sound and fury, though, was the incident’s implications for the federal administrative state. As G. Edward White has noted, the Walter-Logan bill was, for its time, a moderate measure. It stopped well-short of Dicey’s ideal. Even its ambiguous language raising the specter of heightened judicial review was dropped before passage. Long before the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 a procedural notion of the rule of law had won broad support.

I’ll conclude this series of posts with the summary of its conclusion I wrote for OUP:

|

| Corrupt Legislation (LC) |

|

| Good Administration (LC) |

Elihu Vedder's two murals in the Library of Congress, Corrupt Legislation and Good Administration, are arresting depictions of the plight the creators of the American administrative state hoped to escape and the sound and just government they hoped to attain. But if they expected to avoid Tocqueville's nightmare, they also knew that administrators would not stay good on their own, and they designed the administrative state accordingly. Much has changed since 1940, including the rise of rulemaking as the most controversial form of administrative action. Still, the emergence of a procedural rule of law during the heyday administrative adjudication remains relevant. First, the various methods of holding administrators accountable tried out before 1940 are part of a repertoire that we still turn to today. Second, this history shows that we can have an administrative state without transgressing fundamental principles of American governance.