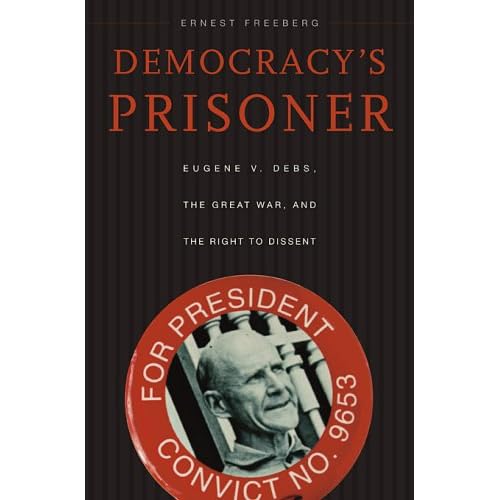

hardson for the Los Angeles Times. Richardson writes, "According to historian Ernest Freeberg, it was precisely Debs' virtuosity that forced America to grapple with the limits of dissent." Debs' 10-year sentence for an Espionage Act conviction based on Debs' antiwar activism

hardson for the Los Angeles Times. Richardson writes, "According to historian Ernest Freeberg, it was precisely Debs' virtuosity that forced America to grapple with the limits of dissent." Debs' 10-year sentence for an Espionage Act conviction based on Debs' antiwar activism Richardson concludes:raised 1st Amendment issues with unprecedented force. Sixty-three years old and in poor health, Debs faced the prospect of dying in prison. His drama played out against a backdrop of revolutionary violence both here and abroad: While he was serving his sentence, a bomb planted by anarchists ripped through a busy Wall Street intersection, killing more than 30 people and injuring 200.

Freeberg shows that in the end it was Debs' popularity, not a knockdown legal argument, that compelled politicians, the mainstream media and eventually federal judges to reconsider the government's power to jail dissidents. The legal justifications came later, after Debs walked out of an Atlanta prison and caught a train to meet his unlikely Republican pardoner, President Warren G. Harding.

If history is what the present wants to know about the past, "Democracy's Prisoner" is teeming with lessons. But above all, it's the story of one extraordinary man's showdown with the establishment -- and how that confrontation turned into a complex political struggle whose outcome was up for grabs. Carefully researched and expertly told, Debs' story also brings a fascinating era into sharp, vivid focus.

"Our confidence in democracy rests on a myth," writes Shenkman. But his argument is "no different from what Alexander Hamilton was arguing more than 200 years ago," Bayard writes. "Indeed, as Shenkman usefully reminds us, our constitutional history betrays from the very start 'a constant tension between faith in The People and contempt for them.'" Shenkman's solutions would be "alarming if it weren't so hopelessly, even endearingly, unrealistic.""No one thing can explain the foolishness that marks so much of American politics," writes Shenkman...."But what is striking is how often the most obvious cause -- public ignorance -- is blithely disregarded ... We feel uncomfortable coming right out and saying publicly, The People sometimes seem awfully stupid."

For starters, they know nothing about government or current events. They can't follow arguments of any complexity. They stuff themselves with slogans and advertisements. They eschew fact for myth. They operate from biases and stereotypes, and they privilege feeling over thinking.