In Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protection Association (1988), the Supreme Court held that it would not violate the Free Exercise Clause for the U.S. Forest Service to build a road through the “High Country,” an area that is sacred to Yurok, Karuk, and Tolowa Indians living in Northern California and Southern Oregon. Unable to show “coercion” of their religious beliefs, the Indian plaintiffs could not rely on the First Amendment to protect their interests in aboriginal territory now owned by the United States. As Justice O’Connor wrote: ‘‘Whatever rights the Indians may have to the use of the area, those rights do not divest the Government of its right to use what is, after all, its land.’’ Scholars have criticized the case as narrowing individual Free Exercise rights and expanding the government’s property rights, to the detriment of religious freedoms. While Lyng deserves this notoriety, an exclusive focus on defects in the holdings obscures other important dimensions of the case. In particular, the Supreme Court’s opinion comes close to silencing altogether the Indians’ perspective on their sacred High Country. Law and religion scholarship, with few exceptions, also ignores tribal voices both on the religious practices and advocacy strategies that were so key to the Lyng case and its aftermath. Indeed, the Forest Service road was never built and the tribes continue to practice their religions in the High Country.

This article offers a tribally-centered version of Lyng, one that is rarely told, at least outside of tribal communities. Based on interviews with tribal members who participated in the case, as well as interdisciplinary research into the anthropology and religion literature, this is a story of cultural revival fueled by the Indian way of life. It is a story of a community forced to defend itself against the assimilationist agenda of the federal government — and developing a contemporary political identity in the process. It is a story of the inextricable relationship between Indian people and lands, in which the Tribes’ attachment to their sacred sites ultimately triumphed over the Supreme Court’s narrow application of religion and property laws. In the final analysis, we argue, the Indian story of religious and cultural persistence has prevailed over Lyng’s ostensible narrative of conquest. Today, as Lyng’s doctrinal legacy threatens to undermine advances made under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, the broader story told here is potentially revealing for everyone concerned with religious liberties in the United States.

Thursday, March 15, 2012

Bowers and Carpenter on The Story of Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association

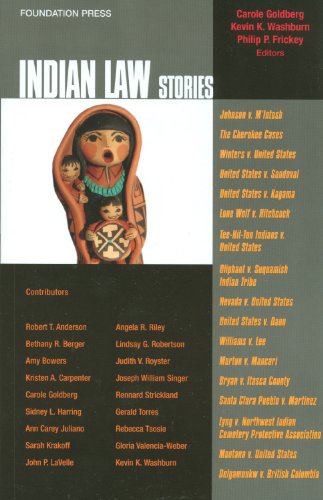

Challenging the Narrative of Conquest: The Story of Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association has just been posted on SSRN by Amy Bowers and Kristen A. Carpenter, University of Colorado Law School. It appears in INDIAN LAW STORIES, Carole Goldberg, Kevin K. Washburn, Philip P. Frickey, eds., Foundation Press, 2011. Here's the abstract: